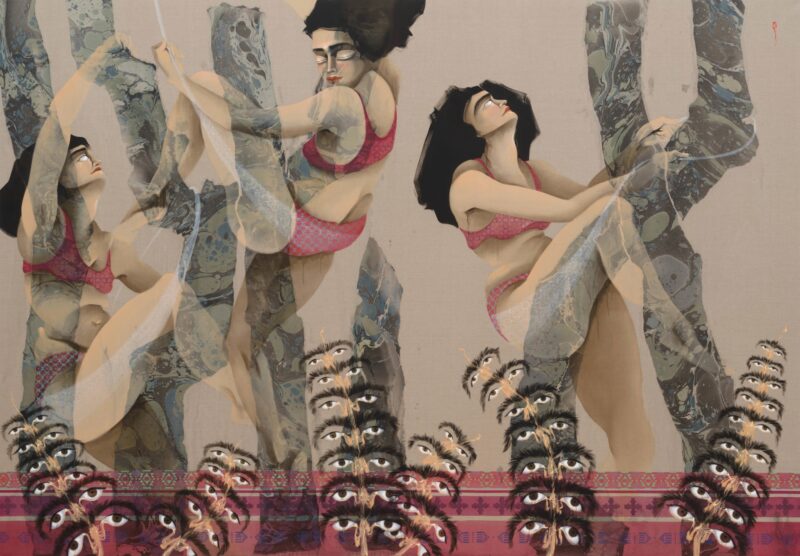

Graham Gussin: In Bloom, 2014

Albrecht Dürer has had a high London profile recently: his own exhibition at the Courtauld; a prominent place in the current National Gallery offering on the Northern Renaissance; and two shows featuring wooden constructions of the form in his famously mysterious engraving Melancholia I (1514). That shape is most often seen as a truncated triangular trapezohedron: I mean, of course, one with its rhombi cut off top and bottom to yield bounding triangular faces, the vertices of which lie on the circumsphere of the azimuthal cube vertices. The shape refers to mathematics and rationality in the print’s schema, which is commonly taken to show Dürer’s personal frustration at how artistic inspiration must fall short of divine inspiration. There’s also a faint skull or ghost on the trapezohedron: that feels relevant at the Freud Museum (to 25 May) where the shape sits in a room emptied of Freud’s accoutrements and filled instead with plain wooden boxes. They, referencing how three of Freud’s sisters perished in the death camps, are of the right scale to hold the contents of an SS Officer’s list – which we’re given – of materials to be requisitioned for Treblinka. Graham Gussin (in a fascinatingly varied show at Marlborough Contemporary, to 12 April, one strand of which linked science fiction to minimalism) re-imagined such shapes as seed pods big enough to hold a human, or else some sort of space craft. Both Balka and Gussin play off how Dürer’s enigmatic form may stand-in for civilised values.

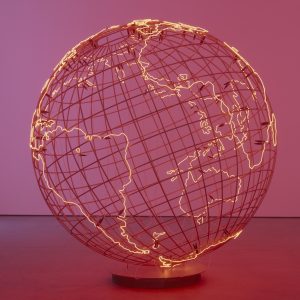

Miroslav Balka: We still need, 2014

Most days art critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in Surrey. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?