The recent announcement of the UK’s top ten most expensive living artists offers a sobering opportunity to think about the extent to which contemporary art has been infected by its entanglement with money. We are used to hearing the same old platitudes about how art was better when it didn’t generate so much money and when artists were not international celebrities, harking back to a time when art was pure culture unsoiled by economics. But, insofar as the quality of the art is concerned, there is no solid connection between art and money; rather, we have a classic case of misplaced romanticism and a rabid fascination with other peoples’ business.

There are two distinct issues in the generalised welter of complaints about art and money. The situation with contemporary art is not quite as dire as we might think once we realise that the connection between art and money – although insidious and inescapable – is very often entirely contingent in particular cases, even if it has the air of necessity when applied to the totality.

The first issue, that the damaging commercial nature of art is new, has its foundation in the dominance of a few commercial galleries such as Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner. On the one hand, these galleries simply take up a lot of headspace with their big-name artists and blockbuster shows, giving less-established artists and smaller galleries something impossibly high to compete with. On the other hand, the exhibition programmes of these galleries is often lacklustre, even lazy, and without any of the innovation you’d hope for in contemporary art because they are always more of the same from the same established artists; even when these galleries do sign a young artist, the decision is driven by market performance rather than by aesthetic judgement.

None of this is untrue, but it must be tempered with a realistic assessment of the rest of the field. At this upper echelon there are sometimes exhibitions of contemporary art which show a continuous contribution to the field even the face of commercialism, such as the recent Baselitz show at Gagosian London. Moreover, these galleries will sometimes put together a museum-quality group show, like Hauser & Wirth’s recent Onasch Collection, where they demonstrate the depth and breadth of their influence with intellectual grace. But it is not all roses at every level beneath this, as in Dante’s hell where all nine circles are as more or less hellish as they are peppered with insight. It is simply a mistake to think that non-commercial galleries, artist-run spaces and bohemian popups are the hotbed of the best art in town. The Tate messes up more exhibitions than it pulls off with a modicum of respectability, just as popup shows are often crammed with poorly executed meaningless rubbish. There is simply a lot of bad art and a lot of diabolical exhibitions out there, no matter how much money is involved. There is just this idea that the underdog is inherently virtuous, that capitalism is inherently wicked and that good art is untainted by commercialism. Furthermore, there is a tendency to look at the rise of late capitalism, sewing its seeds in every facet of modern life, and to think that art’s connection to this is both new and inescapable.

The idea that it is new is true in the sense that capitalism is relatively new in human human history. There was a time when so much art was not linked to so much money, but that is the same time at which food, medicine and energy were also not linked to so much money. But it is erroneous to equate this newness – a contingent historical phenomenon – with the false memory of some time when it was not this way, for that was a time when, without all the money, there was simply less art, which was less accessible and more underfunded. In short, late capitalism is, directly and indirectly, the chief benefactor of all the art we love and loath.

In discussions of modernity, especially in those about capitalism, there is a powerful idea known as ‘the myth of original fullness’. It is used to debunk misplaced romanticism about life in pre-modern or pre-capitalist societies by pointing out that those who attempt criticism of contemporary circumstances by harking back to some simpler time are buying in to a mere myth about how life was better or fuller or more satisfying before the advent of modernism, capitalism, industrialisation or whatever. The fact is that, although these things have brought their ills, they have brought about an overall improvement in the conditions of daily life. Just as we have no wish to return food production to a feudal system or to struggling farmers who lack the reach to make and sell enough produce, nor do we have any desire to return to the dry academic salon art or to art being a privilege of the rich. Capitalism has helped us to shake off these kinds of social ills to such an extent that the better past you wish for is simply a myth.

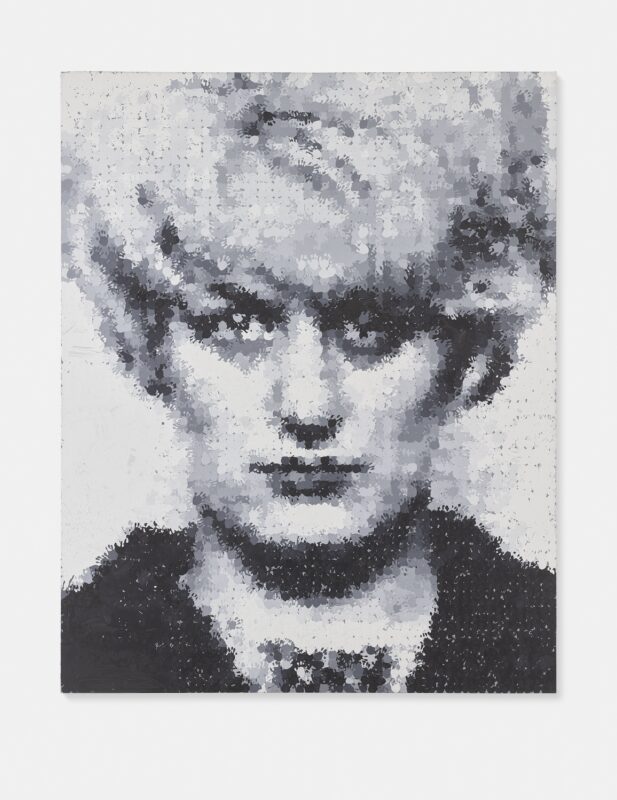

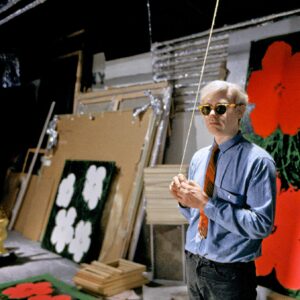

The second issue is the tendency to think that the quality of art is damaged, or otherwise affected, by infection with money. Again, this is a generalisation based on the observation of the art market, where a lot of trash sells for a lot of money based purely on high-class gossip. The problem here is not just about the quality of artworks, but is also a warranted concern about the way in which money enables artists to mass-produce: the Hirst-Koons-Warhol-type production line churns out more of the same because demand funds supply, and not because it is concerned to make art. Essentially, it is the fact that money leads to mass-production and mass-production leads to boring art, rather than that mere money makes bad art, that is the crux of the problem.

And so to the UK’s most expensive living artists, whom artnet ranks according to highest price paid for a work at auction. A secondary market analysis is useful because it divests the result of the interminable power of mega-galleries and the artists’ ability to control their market by artlessly manufacturing market-ready rubbish. All we have here is the price that someone is willing to pay for something that someone is selling, where all that willingness is founded upon individuals’ notions of value. If you are looking to price as an index of quality, then these results are wonderfully inconclusive.

Whilst Hirst is obviously at number 1, you’d expect master craftsmen like Hockney and Auerbach to place higher than 4 and 7 respectively. You’ve got modern masters Gilbert & George at 8, while the difficult Glenn Brown and perennially uninteresting Antony Gormley are at 3 and 5. Bridget Riley bizarrely comes in at 6 while Peter Doig understandably makes it at 2. The bottom end is taken up by Jenny Saville at 9 and Allen Jones at 10. It is a mixed bag, for sure, and surprisingly for British art full of surprises, lacking as it does money-spinners like Rachael Whiteread or headline-grabbers like Tracey Emin. The top ten highest prices paid at auction for living British artists just don’t make any sense if you think that money denotes quality.

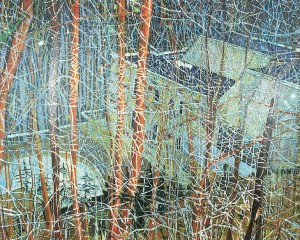

Gormley, for example, is very popular, but not very interesting, but ranks higher than Gilbert & George who have been consistently brilliant for nearly half a century. The fact is that Gilbert & George keep their prices low and rarely appear on the secondary market, while Gormley is in high demand from collectors who will buy any slice of the action just for the sake of it. Jenny Saville is a great painter, but it is hard to believe that she is better than Leon Kossoff or Lucien Freud. Doig’s place is well-deserved, since he has not only put in the hard work but his makes magisterial paintings that will stand the test of time. It is not at all clear that Reilly is much better or worse than Hirst for innovation throughout a career, but she is more accessible and has spent her entire career honing a specific craft.

The point is that the market, at its most immediate and virile, is no judge of quality. The involvement of money in contemporary art does not tell us anything about the quality of art because it is only the price someone will pay. The quality of art, after all, is a value judgement made by an individual at a certain point in time for their own reasons. So in the great contemporary art shop, the shoppers gather to make judgements of culture in the face of a market which makes pronouncements of quality so loudly that you cannot hear the whispering refrain that goes ‘what you see is what I sell’.

Words: Daniel Barnes