The price of art is a much discussed and much maligned phenomenon. But whilst there may sometimes be good grounds for suspicion, a lot of what we hear about the price of art is a wilful fantasy of the media, fuelled by a perennially disingenuous market. The stories we hear about prices are much more like Daily Mail scare-mongering than they are like financial data.

The fact is that not all contemporary art sells for astronomical prices. The $10million for this or £25million for that are the tip of an extremely large iceberg and, of course, they make the news because everyone loves a sensational story. The reality of it is that, although contemporary art is out of most peoples’ price range, it is much more modestly priced than the hype would have us believe. Even those artists who are the cornerstone of the establishment, having been part of the Great Boom, such as Tracey Emin, rarely if ever reach the half a million mark, normally selling for not much more than a couple of hundred thousand. And those are the second tier of big players under Hirst, Koons et al. Beneath that there are so many tiers of more moderate prices. In truth, the ruling mythology of high prices is at best an over-popularised snapshot of a tiny sector of the market and at worst a deliberately exaggerated confection of a conspiracy between the market and the media.

In order to grasp the logic of the pricing system, and to see wherein the horror stories of high prices lie, it is important to see the distinction between the primary and secondary markets. The primary market is the galleries which are the first point of sale for new artworks. They behave essentially like shops, pricing their wares according to how much profit they need to turn. As such, prices will be determined by a strange combination of the notion of prestige (of the artist and the gallery) and fairly ordinary business concerns. Viewed purely as retailers, galleries are free to set their own prices and if a potential customer doesn’t like it, then they can go elsewhere. They operate, like all other businesses, on Friedrich Durrenmatt’s maxim ‘If you can’t afford to dance, then you have to put off dancing’. The only interesting thing about pricing in the primary market is the fact that it is so opaque: rarely, if ever, are prices made public or otherwise discussed, and even if you ask you will probably not be told. Nobody really understands why it’s such a secret.

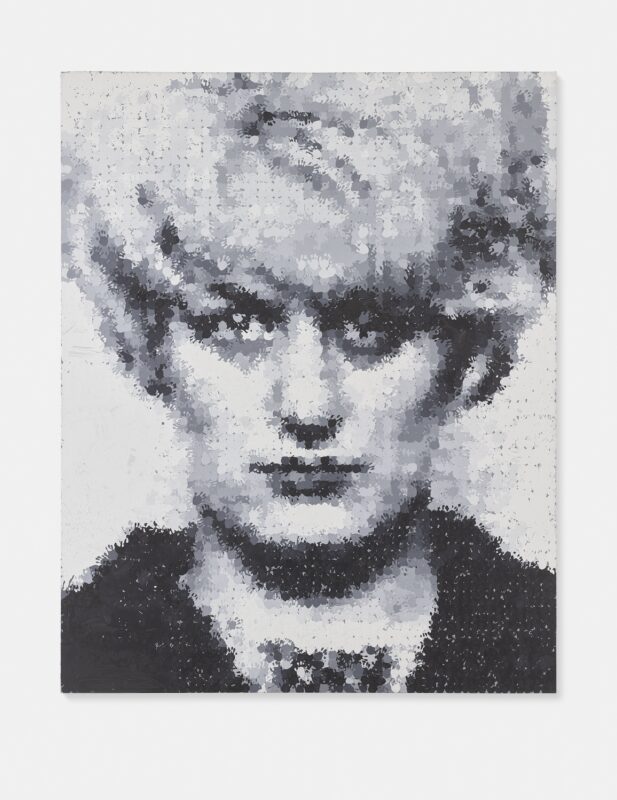

The secondary market – auction houses and trumped-up second-hand dealers – is where the magic really happens. By the time an artwork is sold on the secondary market it has lived a life of its own and has gathered a history: it has been shown in this or that museum, written about by someone with initials, talked about at parties and generally had its value increased by the right kind of exposure. It is, if you like, the case that the primary market deals in economic values, while the secondary market is all about accrued cultural value, for at auction you are buying more than a thing, you are buying a living piece of our collective cultural history. This, in addition to the adrenalin rush of the auction itself, accounts for why such high prices are realised at auction.

Another factor which clouds popular opinion on the prices is the appearance that prices of artworks only ever go up. As a matter of policy, galleries never put an artist’s prices down, since that would be to suggest that the artist is no longer any good, like a sad reduced loaf of bread at the end of a long day. At auction, things are a bit trickier because there is less control over prices, but even when a work does sell for less this time than it did last time, the artworld is ready to explain away the anomaly or to simply say nothing at all because what is at stake here is value.

Again, we find ourselves right back at that insidious notion that price, a construct of the market, determines value, an essential cornerstone of the intellectual contribution of art to culture. The artworld wants us to believe in high prices so we are assured of quality and value in contemporary art. Given the opacity of prices in the primary market, the secondary market – with the thrill and drama of the saleroom floor – is co-opted into generating the ticker-tape that tells of so many scandalously high prices. The minority of cases in which the numbers are vast are held up as horror stories to shock us into implicitly accepting the value of art based on its price. The point is that they want us to believe that art is reassuringly expensive all the time.

Words: Daniel Barnes