The relationship between art and money is complex because it is necessary to the very existence of art in capitalist society, at the same time as being a threat to the integrity of art. This cannot be simply attributed to the onward march of global capitalism; rather, something happened in art itself that was the catalyst for it all. Let’s take a moment to tell this crushingly postmodern love story and to think about how we, the contemporary artworld’s impoverished children, might best accept the tricky relationship that has spawned us.

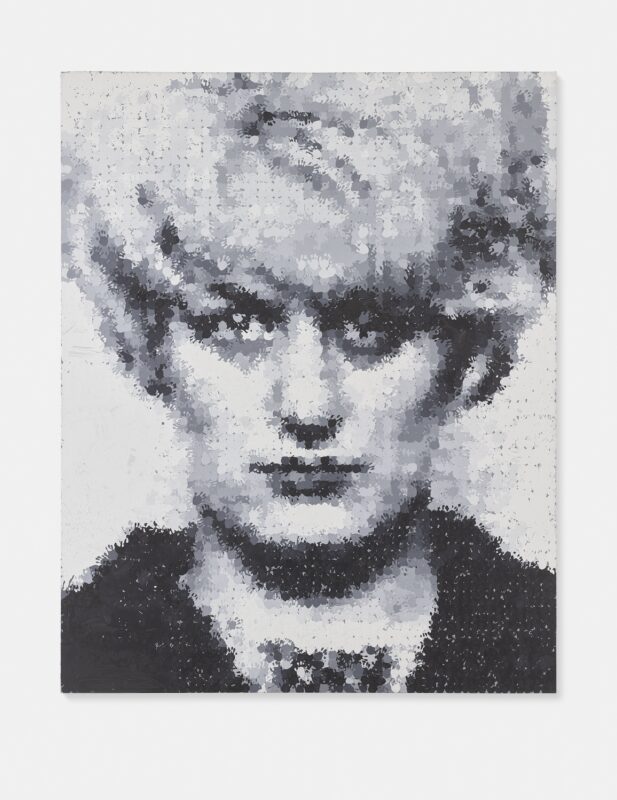

For my generation, 8601 diamonds signalled a serious affair between art and money that shows no sign of abating, not even when an appalled Kirsty Wark pointedly challenged an obstinate, baffled Damien with the question, ‘£14 million of diamonds and platinum. Is there nothing in your mind that thinks there’s something obscene about that?’ But it was Warhol who cast the spell that entangled art and money. First, he made high art about low culture, which enchanted the artworld with its sheer ordinariness, placing art within the consumer society as both luxury good and reflection of society itself. And second, he made the studio emulate industrial mass-production by delegating the work to assistants, speeding up the rate of production. This was art’s industrial revolution, which gathered serious momentum in the 1980s when the prices of high-rollers like Basquiat, Kiefer, Schnabel and Koons began to rocket. Then, in the 90s, it happened all over again with the YBAs until Hirst led the way into the 21st Century, setting ever more records, pulling stunts with That Skull and That Auction.

This is how the star-crossed lovers met: Warhol introduced Art and Money on a blind date over a Brillo Box, they embarked on a whirlwind romance before getting married, battled in sickness and in health, spawned many brattish children along the way. And to this day they are very much in love.

In 1990, the global art market was worth $27 billion, and in 2007, before the global financial crisis, it was closer to $66 billion. Interestingly, after the crash the art market remained largely unharmed, with global sales totalling $60.8 billion in 2011. In 2012, that figure crept up again, signalling another year of steady growth since 2001 where art outperformed equities markets, reaching $64 billion. On Tuesday 12 November 2013, Christies New York set the world record for total sales in a single auction at $691 million, including an eyewatering $142 million for Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969).

The numbers are beguiling. Even if you shut out the noise from the fact that art proved perversely immune to global recession, there is the unfathomable fact that only a small handful people have spent $64 billion on art. The blunt end of these numbers is the fact that art is just stuff: not stuff like minerals or oil which are expensive to produce, since most art is made from cheap, readily available materials; it is not stuff like food or construction materials where that amount of money sustains so much life; and it is not even luxury stuff like Armani suits that cost more than a Ferrari that can be put to good use on a daily basis. Art has to have its kudos constructed in critical acts of convolution, and it is stuff which – for the most part – is only experienced fleetingly and by relatively few. It is not that art is inconsequential, but just that, given what it really is in the grand scheme of stuff, its global market value is a baffling affectation of modern life.

These global sales figures, which cause equal measure of apoplexy and hubris, are the result of auction houses, private sales and commercial galleries. The relationship between art and money is very difficult because these sales involve not only a miniscule fraction of all the people living in the world today, but also a tiny portion of those people who make up the global artworld. The artworld, as far as money is concerned, is a petulant microcosm of all the world’s inequality and injustice.

But rather than display the worst excesses of liberal critique by adolescently rebelling against this fact, we need a way of dealing with it. Isabelle Graw characterises the art market as a form of ‘cognitive capitalism’, whereby knowledge has a value, so the price of an object is eternally justified by the intellectual acumen attached to it. So artworks have a dual nature, she says, following Bourdieu, as a cultural asset and a commodity. The two are separate and interlinked in such a way that cultural value makes the artwork priceless, but market value ensures that it must necessarily have a price.

The artworld, as a multifaceted whole, consists of a large majority who don’t make money from art, or barely make a living. Given that the artworld is this shining beacon of widespread inequality and that we don’t want to give up art altogether in some eternally pious cultural Lent, we need a new way of thinking. A new way which does not obsess over the numbers and the inequality. We need to accept that art is just stuff, and capitalism is all about the rapturous exchange of stuff, most of which we will never be able to cradle in our wanton arms. That is, we need to accept that art as a commodity is out of our reach and the people within whose reach it is are so socially and psychologically distant from us that they are a mere irrelevance.

We need to understand that the core, unflinching value of art is cultural: it is important in and of itself because it enriches our lives in spite of the slings and arrows of capitalism. The money surely makes a lot of art possible, which is no bad thing, but it is not part of the real value of art as a cultural product for a mass audience, which is what is really important. It is as if we must continue to love our wonderful mother who gave us life, and merely accept the convenient existence of our odious step-father who makes mother happy and our lifestyles possible.

The love story of art and money is set to run and run like a great soap opera, and although it seems toxic, it is subsidiary to the main plotline about our own magical affair with contemporary art which relieves the tedium of our crushing lives under late capitalism.

Words: Daniel Barnes