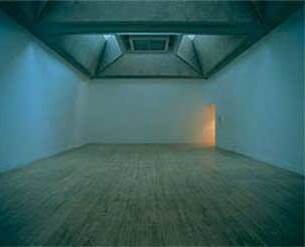

Creed, Martin. Work No. 227: The lights going on and off 2000 – previous installation at the Tate

Tate Britain has just purchased and is reshowing Martin Creed’s Work No. 227: The lights going on and off.

This might have felt familiar enough to pay deserve minimum attention, but for two factors. First, the room was closed off as the installation wasn’t working – or, should I say, only half of it was working – the ‘off’ half. Five seconds on, five seconds off: how hard can it be? Apparently there was more to it than a blown bulb: attendants explained that they’d been entertained by daily visits from electricians seeking to correct an overheating problem. Second, Tate has just paid around £100,000 for the work. What has it got for that? Not, I suppose, the right to turn their lights on and off, but the right to attribute doing so to Creed. That brings in the essence of his work: a poignant desire to avoid mistakes by avoiding decisions. A door won’t be open or closed, balloons will half-fill a space, a drawing will last till the ink runs dry. Maurizio Cattelan, in 2004, thought Work No. 227 ‘looked like a mood swing’ with its ‘ability to compress happiness and anxiety within one single gesture. Lights go on, lights go off – sunshine and rain, and then back to beginning to repeat endlessly.’ Is it worth the money? First I think so, then I think not.

Creed, Martin. Work No. 227: The lights going on and off, 2000

Most days art critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in Surrey. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?