Bedwyr Williams, ‘Wylo’, 2013, Mixed media (Venice Biennale).

Bedwyr Williams, ‘Wylo’, 2013, Mixed media (Venice Biennale).

Interview by Yvette Greslé

Bedwyr Williams is finely tuned to the minutiae of everyday life (its objects and events; its characters and types). He works across media – moving image, performance, objects and installation. The comedic, the absurd, and story-telling are threads that run through his practice. The stories he imagines and narrates (in performances, film, and indeed in his work as a whole) are non-linear in structure and form. They appear to be constructed out of arbitrary ideas and snippets of information. These stories crisscross the realms of myth, fairy-tale, the language of consumerism; and his own memories and thoughts.

His sharp humour (and astute observation) cuts through the ridiculous aspects of what it is to be human – the petty struggles, and the desire for acceptance and belonging. Williams often pokes fun at the language of fashion and consumerism, its all-pervasive presence in twenty-first century life, and its relationship to how it is we navigate the world and each other. Groups, social systems and the language of belonging and exclusion are humorously restaged in works that play with the idea of the art world, clubs and societies, masculinity and fashion. Wearing his famous hat Williams invokes Shakespeare’s Fool, the figure who (shielded by his wit, and his outlandish costume) can say almost anything and get away with it. In invoking the Fool, Williams stages performances that recuperate ancient questions about the role of the artist and the relationship between artist and society. Recent works (including those produced for the Venice Biennale) build on ideas of story-telling, humour and close observation. Moving image work – ‘The Starry Messenger’ (on show at Venice) and ‘Diminuendo’ (exhibited at Ceri Hand) – are works that bring together many of Williams’ concerns to date. Fragmented narratives suggest the arbitrariness, and sensations of inner worlds (thought processes and memories). These are woven into texts and images that are beautiful and magical; but also absurd, scary and repulsive in a visceral way (I think of close-ups of slimy snails in ‘Diminuendo’; and the camera’s proximity to a mouth and teeth at the dentist in ‘The Starry Messenger’). Film is a versatile medium for an artist interested in closeness and proximity; the possibilities of juxtaposition; and the sensory and temporal displacements of dreams, memories and inner life.

Bedwyr Williams and ‘The Starry Messenger’ is a Collateral Event at the 55th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia 2013. It is jointly curated by MOSTYN and Oriel Davies and supported by the Arts Council of Wales. The Biennale closes 24 November 2013.

‘Diminuendo’ (2013), a HD video work is part of the group show ‘Implausible Imposters’ at Ceri Hand gallery, 6 Copperfield Street SE1 OEP. The gallery is open Tuesday – Saturday (10am – 6pm) and until 8pm on the last Friday of the month. ‘Implausible Imposters’ runs through to 10 August 2013. (www.cerihand.co.uk). Bedwyr Williams, ‘The Depth’, 2013, Mixed media (Venice Biennale).

Bedwyr Williams, ‘The Depth’, 2013, Mixed media (Venice Biennale).

I am always struck by how storytelling is so much a part of your work.

I think that telling a story is quite an important part of growing up in Wales (in my part of Wales where I grew up). My grandfather was quite a raconteur. He would tell amusing stories about people he’d come across. There are people who I know now who are not comedians by any stretch of the imagination but they have a talent for telling stories about weird situations. I think I’ve always had my ears open for snatches of stories about people (hearsay, and little half-truth stories).

It seems to me that you really embody the stories that you tell (that you really live these stories). Story-telling is so strong an aspect of the film you made for Venice and ‘Diminuendo’ at Ceri Hand.

I write the stories down in little chunks. Then I get rid of the ones that I don’t like and then I re-order them. The stories that make up the film in Venice (‘The Starry Messenger’), and ‘Diminuendo’ were constructed in the same way. Each section is about four or five sentences long, and then I just make a sandwich with them. I don’t think I could ever write a book because I’m not interested in linear narratives. I like mini-narratives.

Your narratives are not about a beginning, a middle and an end. You write these mini-narratives as you come up with them? It’s not a formalised process?

If you think about your own brain and how it recalls stories, it doesn’t recall anything in a linear pattern does it? That’s why there’s something almost unnatural about a book.

Do you come from a background where oral traditions of story-telling are very strong?

At school there were a lot of fairy-tales, ghost stories, and superstition. I’m interested in the stories that people tell about things that happen.

Do you deliberately cross genres? Your narratives sound like an assemblage of different sources. In ‘Diminuendo’ there’s a sense of fairy-tales with all their magic, and their beauty and darkness. But there seem to be other sources too (I pick up on advertising language and imagery).

I didn’t want it to look like an artist’s video. There’s a kind of artist video isn’t there? I tried to make it look almost like a 6th form project. If you imagine a 6th form project with 20 different students putting all their things together. It’s disjointed in that way. It doesn’t have a visual style that runs all the way through. Little bits of story are sandwiched together. What were the ideas that drove the Venice work?

What were the ideas that drove the Venice work?

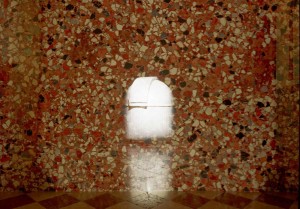

It’s about the microscopic. The tiny fragments of stone that are in the terrazzo floor (at the Ludoteca Santa Maria Ausiliatrice). But also it’s about the astronomical, about outer space and how the microcosmos and the cosmos are similar. How we perceive them is similar. I’ve just more or less riffed on that idea in different scales, and in different mediums.

Was the site of the work important, the idea of it as a place?

Not so much that it was in Venice or that it was a church. It was more about the actual material of the building. I thought if you were worshipping there and you were bored by the priest then you could disappear in the floor.

For me, a lot of your work is about arbitrary things in everyday life: overheard conversations, or innocuous events. I’m interested in why you’re so interested in the mundane, the banal and the things often taken for granted. You draw out the absurdity of everyday life: your humour is also quite cutting.

I think I’m just obsessed with minutiae. If I make new work (and I try and do something else) it will always come back to super detail. I work from that. I think it’s why I moved back to Wales. I like London but you never get enough information about one person here to create a story about them. London is international and transient. It’s not a good place to study characters. Too much changes all the time. There’s more space in the provinces to look at things I think. Bedwyr Williams, ‘The Northern Hemisphere’ (Detail), 2013, Mixed media (Venice Biennale).

Bedwyr Williams, ‘The Northern Hemisphere’ (Detail), 2013, Mixed media (Venice Biennale).

A lot of your work is about having time and space to observe and think. Is place then important to you?

Context is important and maybe situations more than place. The potential for failure in the provinces is so much more sad. If you make a fool of yourself in the provinces people remember forever. It can be excruciating. And I like thinking about that uncomfortable in-between.

The feeling of discomfort is an important part of your performances. You make me ask: ‘What’s the space of the artist?’Does the artist perform a social role? That hat you wear makes me think of the Fool. You wear that hat and then you can say whatever you like.

Artists can be horrible. My mother made a new hat for Venice.

Do you think very carefully about the way you deliver your performances. They’re quite deadpan. Emotion is not part of the delivery.

When I write it I think I’m going to say it in a different way but it always ends up in that same voice.

What role did humour play in the Venice work?

In the work in Venice there’s not lots of humour. There’s the sound of a man crying in the Observatory. Depending on your point of view that’s quite funny. The video is quite humorous (in a way) but it’s dark as well. I think Venice is like that – the Carnival thing. It’s not a friendly funny is it? It’s about masks and slightly scary funny.

Did it appeal to you, that folkloric, magical, carnivalesque aspect?

I would love to go in a time machine to see early carnivals in Venice. The shops there are full of all the costumes but they’re really modern versions. I’d like to see what the carnival looked like 100 years ago. It must have been really extraordinary then.

What observations do you have about the work for Venice?

What I realised was that it’s about minutiae. I realised that some of the scenes in the film were shot with a macro lens so they’re really close. I think that’s something I’m interested to do more of. I like the coupling of the minutae of the story with the minutiae of the visual. There’s some slugs in ‘Diminuendo’ (at Ceri Hand). I filmed them and I found them so repulsive. Bedwyr Williams, ‘The Starry Messenger’, 2013, HD film, 2013, 16:9, 15 mins (Venice Biennale).

Bedwyr Williams, ‘The Starry Messenger’, 2013, HD film, 2013, 16:9, 15 mins (Venice Biennale).

What was the process that drove the film for Venice: ‘The Starry Messenger’?

I worked with two guys who usually make music videos in Cardiff. I wrote the script. I told them that I wanted it to look like Italian Mondo films (‘shockumentary’). They’re just really visceral (lots of jump-cuts). I asked them to make it look like that. In a way I gave them a lot of freedom but they had to follow my script and I performed it. I liked the idea of not making it look like an artist’s video (and of working with makers of music videos). They have a different point of view. The film uses choppy editing, they’ve gone quite crazy with the sound and they’ve also used a lot of stuff on the computer to warp the image and stretch it.

Following Venice what would you like to think more about?

I think it’s more small stuff. Looking down and inwards.  Installation shot of ‘Diminuendo’ at Ceri Hand.

Installation shot of ‘Diminuendo’ at Ceri Hand.

‘Implausible Imposters’ at Ceri Hand gallery (www.cerihand.co.uk) closes 10 August and includes Jonathan Baldock, Mel Brimfield, Grant Foster, Sophie Jung, Matthew de Kersaint Giraudeau, Jen Liu, and Bedwyr Williams.

All images courtesy of Ceri Hand.