Yvette Greslé talks to emerging New York based artist Conrad Ventur about Montezland – his current show at London’s Rokeby gallery (www.rokebygallery.com). The exhibition runs through to 14 March.

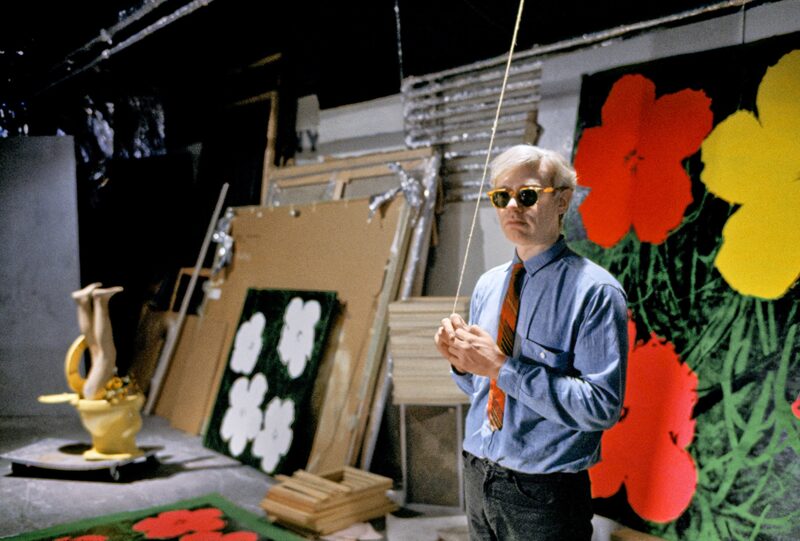

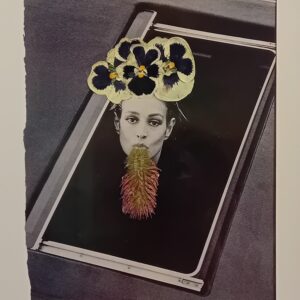

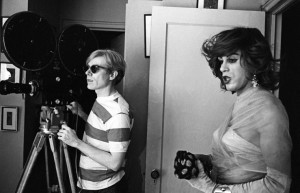

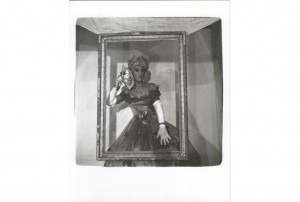

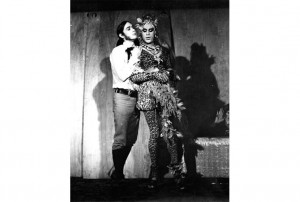

Ventur (b.1977) is a graduate of Goldsmiths College. His work has been shown in the UK, North America, and Europe: exhibitions include curated shows at New York’s MoMA PS1, and in 2012 his ’13 Most Beautiful: Screen Tests Revisited’ was collected by the Whitney Museum of American Art. Montezland is an expanded portrait of Mario Montez one of Andy Warhol’s superstars and a legendary figure in the underground cinema and theatre scene of New York City. Ventur opens up a visual archive that brings together various inflections and traces of Montez in the work of (among others) Warhol, Jack Smith and Ventur himself. Montez (b.1935 in Puerto Rico) is remembered by avant-garde audiences for his homage to the 1940s actress María Montez and roles in Jack Smith’s ‘Flaming Creatures’, ‘Normal Love’ and ‘No President’. He appeared in thirteen Warhol films. Montez is also a founding member of Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company and played the lead in José Rodriquez-Soltero’s ‘Lupe’. In 1977 Montez retired his drag persona and left New York for Orlando (Florida) until 2010 when he re-surfaced.

Ventur enters an archive of memories, fragments and cultural objects: human traces folded into the sphere of documented history. He produces a carefully curated visual-aural space that draws our attention to time as a series of overlays and relations shifting (discontinuously) across multiple registers, speeds, affects and memories. Politically it is an archive that draws our attention to the politics of gender identity, desire and sexual preference. We are reminded too of the enactment of celebrity and spectacle by 20th century experimental performers, artists and film-makers. We imagine (not simply with misplaced nostalgia) the histories and meanings of these politics, and these performances. While, in the 21st century, we are subsumed by uncertainty, political violence and capitalism’s entrapments.

How did this show come about? How did you come to this character and this archive?

In about 2009 I started working on a project to redo Andy Warhol’s screen tests. These were motion portraits that he did in the ‘60s – there were 370 that he’d done. I really got into this project out of curiosity to see who was still alive. What were they doing? Would they be interested in having another motion portrait done?

You were interested in Andy Warhol?

I wasn’t interested in Andy. I was interested in the people in the screen tests. I like the format of the screen test. I came to it from a portraiture background, using photography. I was primarily a photographer for a decade. The screen tests are portraits. It’s a format that works when you approach someone who is 80 years old and all you want is to hear their stories, and maybe gain their friendship, and all they have to do is sit there for a couple of minutes. It’s something easy for an older person to do. They have to get past all of the crap of history and all their associations with Warhol. Some of them have felt that they have been exploited (that’s in the past and they don’t want to bookend that with anything different). I find all that really interesting.

What is it about portraiture and people that interests you? What do you think brought you to these interests?

I think this is something that will be revealed over time. I think I’m interested in change. I’m interested in taking these pictures and then revisiting these people later. And even younger people that I photograph – coming back to them in a year’s time. I think it’s a way of freezing things for a second.

As a photographer you work primarily with portraiture and both younger and older people?

Mostly older people but I’m starting to work in ensembles where I put older people and younger people together and we do performances.

Is there something interesting for you about age?

I think there are echoes that are present within younger people. They’ve put their own cultural DNA together and they’ve gotten it from other places. What I find interesting is when I pair legends (who were busy in the ‘60s) with younger counterparts (two or three generations younger). I think that’s interesting.

I notice that a lot of people born in the ‘70s appear to have this nostalgia for the ‘60s and ‘70s – artist’s might draw on music, family histories etc.

I haven’t unpacked the word nostalgia so much. My work isn’t about me pining for a time that I think of as special, or doting on that in some way. I think I’m peeling it open in a different way. I enjoy the music and I enjoy some of the stories but it goes further than that.

Do you like story-telling? Do you see yourself as a story-teller?

I don’t do it in a way that’s traditional.

What’s interesting for me about the show (and the telling of a story) is the choice of screens and surfaces – the ways in which images are fragmented across media (fragments of a narrative). The arrangement of video monitors within the space, the arrangement of film, photographs (archival material and material you’ve re-staged or produced yourself in collaboration with Montez).

This is an expanded portrait really. It’s a tribute to Mario Montez who I met about three years ago. I met him because I was re-doing Warhol’s screen tests. He had been hidden for 35 years up until fall 2009, and then I found out he was coming out of retirement. He was on my list as somebody that I wanted to do a screen test with. We met and we hit it off. We work well together and we trust each other. Here, almost 3 years later, I’ve put all my research together: 11 artists who worked with him in the ‘60s/early ‘70s, and objects that they’d collaborated on. I put them all in the same space -Takahiko Iimura, Avery Willard, Andy Warhol, a couple of my photographs, Leandro Katz […].

It really is a cultural archive that you’ve opened up, and it has personal inflections. It’s not an archive in a formal, official sense.

You might encounter this material in a text or an academic book but this might be the middle section where there are 10 photos and then there’s text that refers to these objects. And you’ll have scholarship about the Jack Smith films or the Ron Rice. But this is the visual expression of this portrait. All of us together across time, all in one space.

Can you give me a sense of the visual process (which is difficult to put into words). The visual process from screen test, to meeting Montez, and then your process. What led to this visual configuration we see here in this show?

As we enter the space, there are a couple of small vintage photographs by the door and it sets the tone for Mario as a muse. They’re all photos of him when he was young. What I’m still working on here is what it must feel like for Mario after decades of having done this work, and now coming back into the world and starting work again with people like me. He’s even started collaborating with others. What that must feel like when some of the films he worked on are now lost. There are two films that are lost and the only thing that remains are a couple of photographs. Some of these pieces are complete. There are threads of his life that we can now see in this space, and some of them are fragments. But I think putting it together is the whole of somebody’s life with all of these absences, and things that are present.

Tell me about the monitors in the middle of the space?

They are 5 different monitors with 5 different artists on them and one is this very famous film with Mario eating a banana in a really suggestive, sexy way. It’s the only film that Warhol got an award for. Mario’s the one who basically invented this obsession with the banana. We’ve come to attribute it to Warhol but Mario’s the one who pulled the banana out of his handbag and prior to that Warhol had not used the banana in his work (to the extent that we now understand it). Of course, we know that Velvet Underground used the banana on their cover.

The banana – It must have other precedents though?

But Mario gets it into Andy’s distribution system which then makes it so iconic to us. We imagine at least that eating a banana suggestively had happened before. But Mario’s clever in that he connected that with Andy’s film practice, and put it in the middle of The Factory and it just exploded. The very first thing I did with Mario was a re-staging of the film of him eating the banana (the original is also on show on a separate monitor). I got Mario to wear the same outfit, eat the banana in the same way. On one monitor there are two of my re-stagings: Mario eating the banana, and a Warhol screen test. Warhol did 13 films with Mario. Some of them are shorter. Andy also had Mario dance so there’s one called ‘Mario Dancing’, and then there are the feature length films.

What about aesthetic decisions that you’ve made in the re-staging of the screen test? Choices such as black and white film, modes of display etc?

The film I use refers to the frame that it was originally shot in. The aspect ratio is 16 to 9 – that’s about me and my time, and my technology, and it’s on video. I thought a lot about it. Should I be doing these on 16mm? Should I take on the cost of doing that? And ultimately I decided it was fine to be in my time.

And when you say video? What sort of video technology are you using?

Current technology: it’s not analogue tape. It’s DV tape. (I haven’t gotten to that thing yet where we say moving image). This is video tape so I call it video (some of my newer performance work is on a little chip the size of my fingernail).

How do you edit?

I edit using Final Cut Pro, on my computer. Jonas Mekas was telling me that I should take 2 minutes 45 seconds off my original tape and slow it down 4 minutes to approximate how Andy would use the projector at a slower speed (so people are just slightly slower than real time). Jonas told me what to do because he’s so familiar with it.

So you’re intervening in this archive materially, and staging these repetitions. As an artist you’re intervening in quite a tactile way in terms of time and duration.

I think of people as material. For me, it goes past the video tape and all that. In some of my other video installations, I was appropriating video off YouTube and using those. Here I feel like I’m taking a person, and working with them in a familiar way.

They become your material substance in a way?

That’s how I think of them.

You think of people you work with as an artist as characters or material substances?

Both.

Tell me about the Ron Rice work on show.

Ron Rice was filming this at the time that Jack Smith was filming ‘Normal Love’. Ron Rice would go off and film in the forest. In Ron’s loft sometimes late at night they’d be fooling around, setting things up. He’s known for this kaleidoscopic editing technique, which inspired me to make kaleidoscopic video installations using prisms.

Explain to me how Rice’s technique works.

He probably did this with optical printing where you just do multiple exposures on the same film frames.

What informed your decision to put the Rice work on the exhibition? It seems as though you’ve thought a lot about the way the show is curated. Everything’s been so carefully thought through.

I had the envelope of the space and I knew that inside that there’d be two zones. Within one zone there would be monitors in the middle, surrounded by photographs. In the other there would be a cinema space. Some of the curatorial decisions are Rokeby gallery, Beth Greenacre.

How did you want the cinema space to speak to the rest of the show?

It can open up for the audience in many different ways. I just wanted it to flow, so that you could have a personalised experience in here. And not get railroaded into any particular spot because I think that’s the sort of portrait it is. As an expanded portrait, there are many points of entry. You can come into the cinema space and it’s isolated and kind of quiet.

Could you speak a little to time in your work? What are the relationships between things like fiction and ‘the real’ or story-telling (or narrative)? Are these things interesting to you?

You’ve seen ‘Sunset Boulevard’ where there’s this silent era movie star and she can’t make it to the talkies, her career collapses. She spends many years in this decrepit mansion living in a fantasy land. She wants to come back. I wanted to find somebody who wanted to come back but was fine having wrinkles, and was happy to reveal what had happened. I didn’t want a Norma Desmond who was delusional and absurd. I found that in Mario. I found somebody who was really happy being old and being complicated.

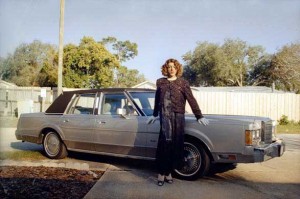

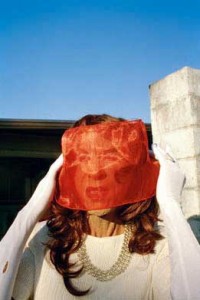

What is the context of the photograph of Mario at the beach? (photograph shown above)

We’re looking at Mario at Key West. He spent about 35 years in Orlando. We come to understand that in ‘77 he leaves New York and he doesn’t tell anyone (just one person). After he left he did no more collaborations. He didn’t wear drag.

What did he do?

He was a file clerk in an office. But a good citizen, working, contributing.

What is his heritage?

Well this is why this photo is important. We have him in Key West. He just moved there last year, and he’s really close to Puerto Rico which is where he’s from. He was born in Puerto Rico. When he was about 8 or 9 he moved to Harlem. He lived all those years in New York. Now in a way he’s going back to Tropicalia.

Montez plays with ‘the exotic’. What’s his relationship to the exotic? The exotic (for me) is something that can be imposed in a way that’s inhibiting.

I think Jack Smith inspired Mario to bring that into the performance. That’s why the work they did together is so beautiful and seems to work. Jack found inspiration in B movie stars like María Montez. And that comes into the collaboration. Mario was happy to take on these characters into his persona, and take them further.

What do you think is especially critical for you as an artist? What’s critical about your practice? What is it you’re reaching for?

I think I’m incredibly skeptical of youth culture and the commodification of the youngster who’s got all this energy. I think as my practice develops, and I get older, I’m trying to peel away the onion of the thing. If you grow up and grow old, what happens? What’s that like? There was this peak moment in the ’60s that people have nostalgia for. What happened then and how does it echo today?