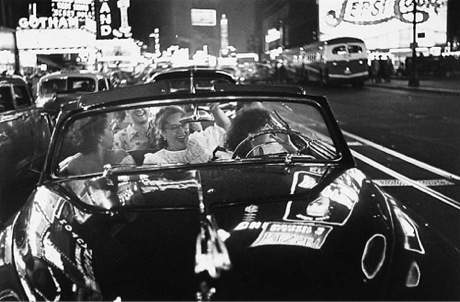

Louis Faurer, Times Square Converitble, New York, 1949

Silver gelatin print (printed in 1980), 11″ x 14″

Corporations Are People Too is a group exhibition of artists whose work has touched on corporate culture and our love-hate relationship to these powerful organizations. In a time where protesters across the country, and the world, are objecting to the influence corporations have over democratically elected governments and one leading candidate for the Republican nomination for President, Mitt Romney, was roundly criticized for claiming during a campaign stop that “Corporations are people too,” a bright spotlight is being shined on the complicated role they play in contemporary life.

The exhibition begins with a selection of vintage photographs by Berenice Abbott, Louis Faurer, Lewis Hine and Dorothea Lange, showing the arc of attitudes in America about the relationship between huge companies and the average person. From Depression-era images of child laborers and migrant workers up through post-WWII images of happy shiny Americans enjoying all the conveniences that modernized manufacturing brought them in their new age of posterity, these black-and-white photos set the stage for a relationship that continues to ebb and flow with the changing economics of the nation.

The exhibition continues with works by contemporary artists that flesh out the complexity of corporate culture as it has evolved to influence, if not define, many of our political and cultural ideologies. A 2005 installation by Yevgeniy Fiks offers a broader look at how we have come to recognize corporations’ individual identities. Fiks sent 100 US corporations a copy of Lenin’s book Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism as a gift for their library, asking only that they acknowledge receipt. The 34 letters he received, some accepting the gift, others returning it, provide a series of fascinating and, in turns, hysterical portraits of the corporate personalities.

Kota Ezawa’s series of IKEA lightbox works (2008), in which he redraws the pages from the international home furnishing store’s catalog, stem from his mixed feelings about our need for furniture chosen not as an object to be kept or cherished but rather as an inexpensive solution to a living problem. Within these paired-down renderings, the catalog pages lose their function as advertisements and their staged domestic interiors become instead theater stages for the drama of contemporary life. In Ian Davis’ small paintings (2011), scores of men in black suits populate landscapes or auditoriums devoid of any clear hierarchy or leaders. In unison they raise their hands as if making a pledge or collaborate to mug other suited men, suggesting armies of blindly obedient Yes Men, answering to a particular culture more so than an obvious power figure.

In Jacqueline Hassnick’s “The Table of Power” series (1993-1995), photographs of uninhabited boardrooms of well-known corporations are completely absent the executives who usually meet there, but still communicate an intimiating degree of order and control. One of the images, totally black, reflects the refusal of Shell Oil to let their excutive boardroom be photographed. People are also absent in the photographs from Philip Toledano’s “Bankrupt” series (2001-2003), but traces of their having been there remain in the emptied offices of corporations that went out of business. Toledano has described these abandoned objects as “signs of life, interrupted,” and they speak to how the corporate experience is a big part of who they are for many people.

The exhibition concludes with an installation by Chris Dorland incorporating large- and small-scale paintings as well as video. The way that many corporations market their (often banal) products to the public by associating our collective ideals and hopes with their corporate brands is one of the themes connecting Dorland’s various series. From his well-known toxic-colored landscapes insinuating the failure of Modernist architecture to realize its promise of a utopian future, to his newer series of decontextualized, muted logotypes and mixed media paintings of sexy, happy people so interchangeable we recognize them as part of an advertising language even without any hint of their ad’s original product, to a new video titled “Restoration Hardware”, these works, seen in dialogue with one another, bring full circle his exploration of the cynical association of progressive values with consumption and desire. Dorland’s work deals head on with how, as he has said, “’Progress’ gets aestheticised and then ultimately instrumentalized by Capitalism.”