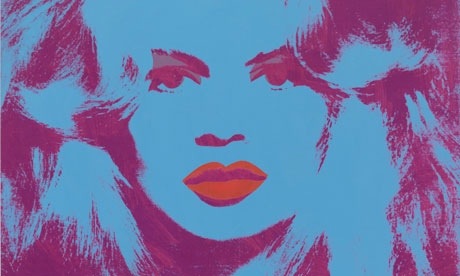

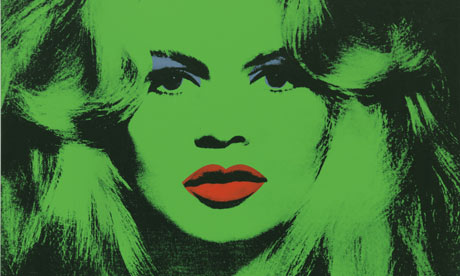

Above and below: Brigitte Bardot, by Andy Warhol (detail, 1974). Photographs: Mike Bruce/Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

Andy Warhol absorbed tons of what we now call “content” into his art. He was a one-man search engine, instinctively latching on to everything that was trending, yet also going deep, dragging up images others would shy away from: photographs of car crash victims and suicides. Words such as “camp”, “kitsch”, “tacky” might seem the right ones to describe his boundless pop cultural appetite; but these are underestimations that glance harmlessly off the cold, shadowed, eerie surfaces of his paintings. It is Warhol’s pure eye, his ability to show an object or a face – whether through the clean drawn lines of his early work, or the silkscreened found images of his Factory paintings – with a pristine clarity and simplicity that focus the mind.

Another chunk of Warhol content will be unveiled in London next month, when a series of 1974 portraits of Brigitte Bardot go on show at the Gagosian gallery. Meanwhile, a Warhol retrospective has just opened at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, drawn from the Artist Rooms collection, together with important loans such as the Tate Marilyn Diptych. So many things to see, and to register impassively in the way Warhol seemed to register them: cow wallpaper and dollar signs, the electric chair and a French film star. Yet in each case Warhol drains away the irrelevant and the ironic, producing a pure, sincere image.

Warhol’s Bardot has a green face and red lips, a blue face and red lips. Her cheeks are perfect, her hair is a tangle of silkscreen shadows, and she manages to be of two times, simultaneously. Warhol made his portrait using a 1959 photograph by Richard Avedon, of Bardot in her youth; the paintings themselves date from 1974, soon after the star of French 1960s cinema announced her retirement. The strong, raw colours, dark shadows and garish lipstick ooze the 70s: these are manifestly paintings from the decadent era of Roman Polanski and Exile on Main Street. So, while the woman in the picture has not aged, has remained frozen in perfect cinematic beauty, the world has got older, saggier, more corrupt. By retiring from the screen, Bardot preserved her young image for posterity: this Bardot will not grow old, even if time moves on. Loss haunts the black shadows of Warhol’s paintings.

I recently stood among soup cans in a Los Angeles museum, contemplating the series of small canvases Warhol exhibited at the city’s Ferus gallery, his first one-man show as a fine artist in 1962. These paintings are not photo-derived, but drawn neatly and carefully filled in to present, each of them, an outsized soup can in just four colours: red, white, black and gold. (There may be some silver there, too.) The cans are all the same, but each is different. Campbell’s soup is exhibited in all its flavours, from tomato to chilli beef. Here, too, it was Warhol’s pure, cleansed, innocent eye that struck you – seeing the beauty in the humblest, most ordinary, least distinguished thing. These paintings are like the prayers of a saint.

Warhol was careful to conceal his faith during his lifetime; serving in a Catholic soup kitchen didn’t really fit with his public image as master of revels at the Factory and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. But you could look at Bardot as his icon of the Virgin Mary. Like the other women he idolised – including Marilyn Monroe, subject of his explicitly religious diptych – Bardot appears here as a remote, superhuman, adored beauty. Women were not Warhol’s primary sexual objects, to put it clinically; but they haunt his art, fulfilling mythological and religious roles. Monroe is a martyr; Jackie Kennedy a mater dolorosa weeping for America; and Bardot might just be the queen of heaven herself, unchanging and immaculate as the world rots around her.

Warhol is pure as the driven snow, his art like a visit to church. Too much of that can get on your nerves, but when you need to see the modern world through new eyes, no one is more honest.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.