Image:Golf Five Zero, (Borucki Sanger), British Army watchtower. Crossmaglen, South Armagh, Northern Ireland, UK. 1999 © Jonathan Olley, courtesy Diemar/Noble Gallery.

In the autumn of 2001, the New York gallery Pace/MacGill showcased American photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s latest project, Heads (2000). A series of large portraits of passersby around Times Square, taken over a two-year period, these were not, however, your traditional candid photogs. By devising an elaborate system of strobe lights, scaffolding and a remotely activated camera, diCorcia had in fact taken street photography to a whole other level, thanks to which he succeeded in ‘invisibly’ snapping photos of unwitting subjects at an otherwise inaccessible close range. One of these Caravaggioesque portraits, Head no. 13 (2000), was that of Erno Nussenzweig. Upon discovering that he was the subject of an exhibition, catalogue and also sale (diCorcia produced ten limited edition prints of each photo) some four years later, Nussenzwieg was less than impressed and promptly sued the photographer as well as the gallery on grounds of infringing his privacy and religious rights (he was an orthodox Jew).

The sticky court battle which ensued arrived to the highest echelons of judicial authority in the city, the New York Supreme Court, who came back with the landmark ruling that the photographs were art not commerce, and therefore fell under the First Amendment, which upholds the freedom of expression. Effectively, what the Supreme Court had ruled was that the photographer’s right to artistic expression trumped the subject’s right to his own image.

Tate Modern’s latest mammoth exhibition Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance & the Camera explores precisely this tense relationship between the photographer, his subject and, of course, the viewer: a relationship which has been bumpy at the best of times.

Image:Walker Evans Street Scene, New York 1928 © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

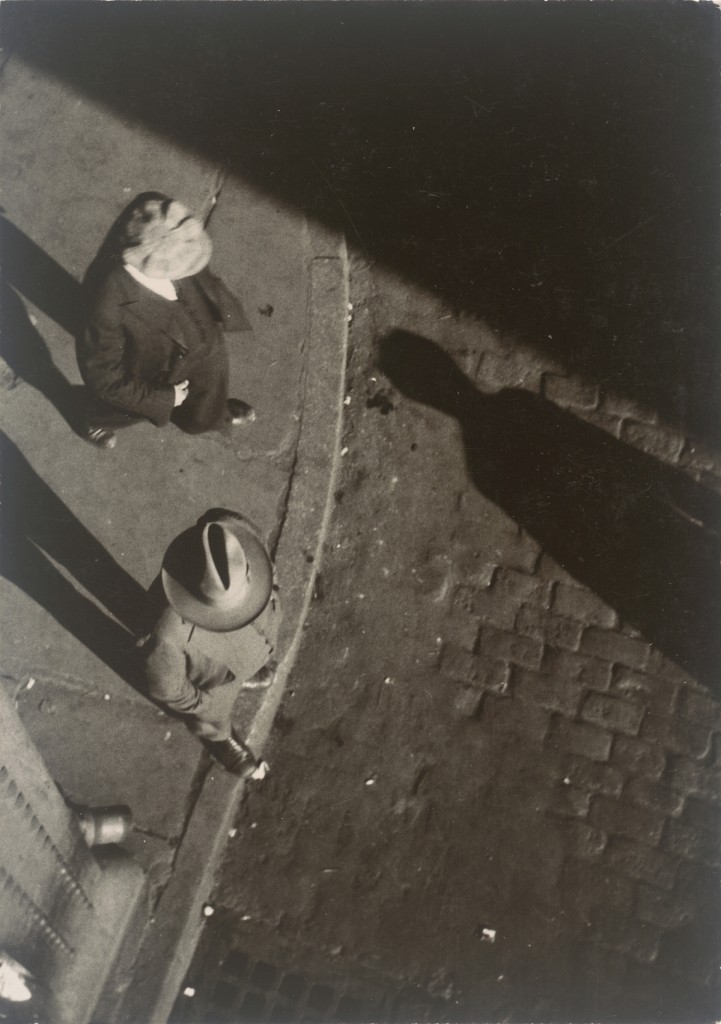

Exposed is overwhelming both for the sheer volume of works on display as well as for the amount of iconic images by photography masters most of us have only seen in books: besides a number of portraits from Heads, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Prostitutes, Calle Cuauhtemoctzin, Mexico City (1934) is also here, as are Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), a selection of pictures from Walker Evans’s Subway Passengers (1938-1941), Helmut Newton’s Self-portrait with Model and Wife (1981) and Abraham Zapruder’s Assassination of John F. Kennedy, November 22, 1963 (1963).

Strolling through the first galleries of the exhibition, it soon becomes clear that from its infancy street photography has determinately (and furtively) sought to capture its subjects unawares in its tireless goal of portraying the ‘real world’. A number of gadgets which would have made James Bond nod in approval lie in glass cases: a shoe with a camera hidden in its heel, a cane with a camera concealed in its knob, and, last but not least, a camera hidden in a watch.

What also becomes evident is the subject-matter: more often than not, whether in the photographs by Paul Strand depicting residents of the poverty-stricken Five Points neighbourhood in New York, made famous by Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, or of children working in mines and factories by Lewis Hine, it is the poor and the exploited who are invariably photographed. Despite the at times questionable methods these photographers have employed, it is largely thanks to their socially-charged work that we have a raw and unrefined picture of a society which would otherwise have remained invisible. Sometimes they also have the power to transform society. It is a triumph of street photography that the photographs of child labour by American photographer and sociologist Hine were instrumental in changing US child labour laws. At Exposed, one can see his Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Georgia (1909), a chilling portrait of a little girl in a grimy dress and apron: her hair held back with a loose bow, she looks numbly at the photographer as she stands between two rows of cotton spinners towering above her.

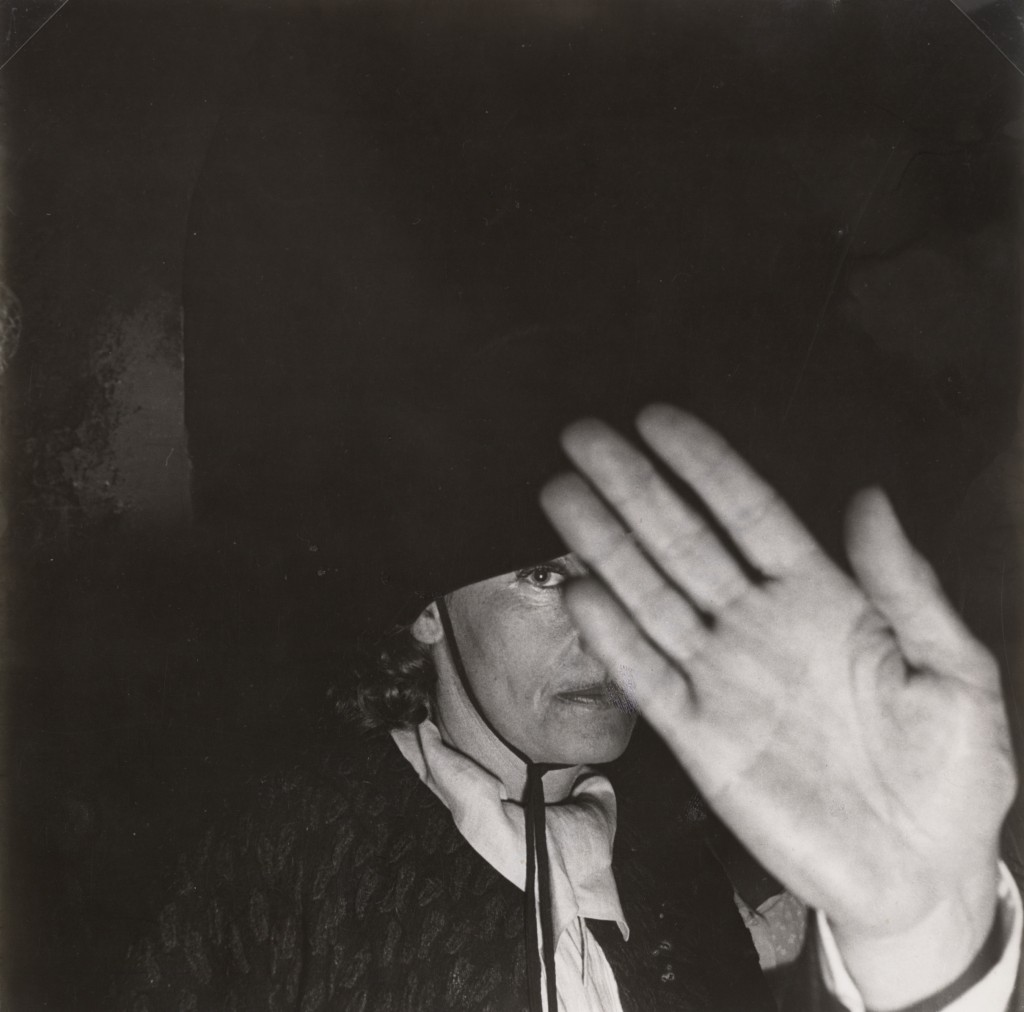

Image:Georges Dudognon Greta Garbo in the Club St. Germain, Paris ca. 1950s

Further along, the walls are lined with a decidedly different kind of photography: row after row of some of the world’s most famous snapshots taken by paparazzi are on display. Perhaps because the intrusiveness of paparazzi has become synonymous with contemporary celebrity culture and trashy magazines, it is startling and incredibly amusing to see a photograph of such a respectable figure as that French painter of ballerinas, Edgar Degas, emerging from a Parisian pissoir, top hat and all (Giuseppe Primoli, c.1889). Several photographs by American Ron Galella, one of the most relentless and successful paparazzi of all, and, coincidentally, Andy Warhol’s favourite photographer, can also be found. His photographs of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor cuddling on their yatch in 1962 exposed their secret affair (also on show at Tate). He was perhaps most notorious for his obsession with Jackie Kennedy, whom he militantly chased around New York until her court orders (first, that he maintain a distance of fifty yards and later in a settlement that he stop photographing her altogether) put a stop to it.

In a recent New Yorker interview with Tad Friend, Ron Galella, now a 79 year-old, remains rather humorously unrepentant, claiming that Jackie “loved being pursued”. Exposed shows a beautiful black and white shot of the back of a (seemingly) young girl sporting a t-shirt and shorts as she runs rapidly away from a pursuer, her hair blowing in the wind. On closer inspection of the title, What Makes Jackie Run? Central Park, New York City, October 4, 1971 (1971), the viewer realises this is in fact Jackie Kennedy fleeing Galella. What is perhaps most shocking about this picture is that Jackie O’ is actually moving, clashing with the image imprinted in our minds of an eternally gathered lady, in her trademark pearls, elegant clothes and faultless hairstyle. It shows a humane and unguarded side to a woman who was otherwise a symbol of perfection and grace.

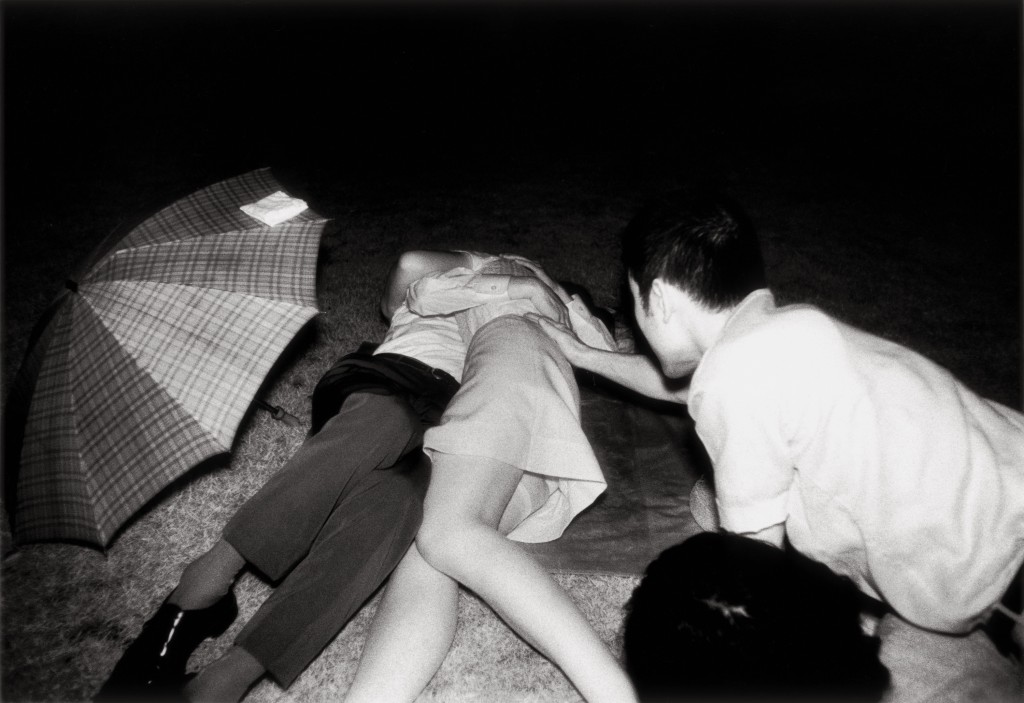

Image:Kohei Yoshiyuki Untitled, from the series The Park 1971 Gelatin Silver Print © Kohei Yoshiyuki, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Other photographs of the more sordid voyeuristic variety are best exemplified by Japanese Kohei Yoshiyuki’s The Park series (1971-1979). Hung along the walls of a dimmed corridor, these black and white photographs have been shot using infrared flashbulbs. In the 70s, Yoshiyuki discovered that in the depths of the night the parks of Tokyo were magnets both for lovers seeking secrecy as well as for packs of perverse men looking to spy on the unsuspecting couples. At first, the photos are simply seedy and unquestionably pathetic: shot from behind, we see a group of three men on all fours looking at a couple making out on the grass, like desperate vultures staring at their prey. However, as the shots continue, we soon realise that these men are not simply voyeurs content to salaciously drool from a distance: they are disturbingly keen to get in on the action, and we see them as they grope a woman’s breast or touch her vagina. Whether the couples ever got wind of what was happening remains unknown. These graphic photographs pose uncomfortable questions about voyeurism: no matter how appalled we are by the photos, we too are voyeurs, peering at the photo as we try to see what it is going on – as is Yoshiyuki, crawling on all fours to expose these nightly perversions.

Image:Weegee (Arthur H. Fellig) Their First Murder 1941 gelatin silver print 267 x 346 mm International Center of Photography, Purchase, with funds provided by the bequest of Wilma Wilcox, 1997 (13.1997)

© Weegee / International Center of Photography / Getty Images

A whole other set of problematic questions are raised by the exhibition’s section dedicated to witnessing violence. Weegee’s Their First Murder (1941) and Marcello Geppetti’s Fire at the Hotel Ambassador (1959) are grim explorations into our own morbid fascination with violence. In Weegee’s famous photograph, it is only one person – a woman who Weegee claimed was a relative of the shot racketeer – to express pain, her face contorted in anguish as she cries in abandon. Amongst the group of children huddled together alternately laughing or posing for a unique chance to get photographed, her grief stands alone and becomes public spectacle. Looking at Geppetti’s picture, it seems that we can’t help but stare in horror as the burning victim of a fire at the Hotel Ambassador in New York flings herself from her window to inevitable death.

Exposed serves as a reminder of just how tortured the relationship between photography and privacy has always been, and how photography almost invariably been an invasive medium. This tortured relationship has reached new heights in a post-September world, where street photographers are ever more constrained in their freedom to document the everyday. It is thanks, however, to this almost lawless and persistent desire to depict a society which is not guarded and posing, that street photography exposes a multi-faceted humanity – one which is diametrically opposed to the glossy, air-brushed images of us, produced by carefully regulated photography. The irony is, of course, that while we actively rebel against our photo being taken, we remain passive and oblivious to what we can see less visibly: the thousands of CCTV cameras recording our lives.