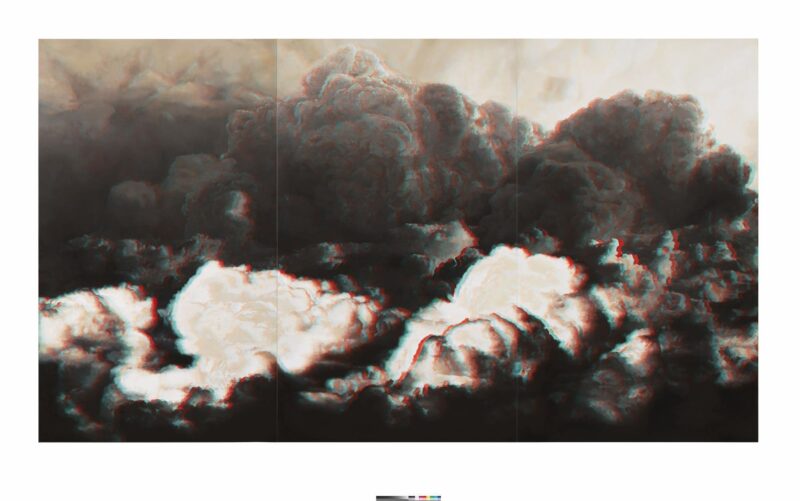

Jeon Joonho, The Whote House, 2005-6. Digital Animation, 32:16 min. Collection of the National

Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan. Courtesy of the artist and Arario Gallery, Seoul ©Jeon Joonho.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art presents the first major museum exhibition in the continental United States in almost two decades to focus on contemporary art from South Korea. Organized by LACMA and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), Your Bright Future: 12 Contemporary Artists from Korea features a generation of artists who have emerged since the mid-1980s—some well-known and others on the brink of such recognition—all of whom work on the cutting-edge of international art trends and within a distinctly Korean context: Bahc Yiso, Choi Jeong-Hwa, Gimhongsok, Jeon Joonho, Kim Beom, Kimsooja, Koo Jeong-A, Minouk Lim, Jooyeon Park, Do Ho Suh, Haegue Yang and the collaborative, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (family names are in bold). Your Bright Future (a deliberately ambiguous title taken from a sculpture by Bahc Yiso) will represent each artist through a large-scale installation or substantial body of work, including site-specific installations, video art, computer animation, and sculpture. The exhibition will premiere at LACMA, which has the most comprehensive collection of traditional Korean art outside of Korea and Japan, from June 28 through September 20, 2009. The show will then travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, November 22, 2009 through February 14, 2010.

“Korea has a vibrant and sophisticated contemporary art scene that is still relatively unknown in the United States,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “LACMA is thrilled to bring this insightful exhibition to Los Angeles—the largest Korean community outside of Korea—particularly as we reopen the museum’s Korean art galleries, providing our visitors both traditional and contemporary offerings of Korean art.”

Peter C. Marzio, director of the MFAH, commented, “The impetus for this landmark exhibition dates back to my revelatory first trip to Seoul in 2004. Four years and countless studio visits later, curators Christine Starkman and Lynn Zelevansky have opened an entirely new perspective on the extraordinary art being made by a generation of Korean artists. We are enormously pleased to have partnered with LACMA on this initiative.”

The contemporary art scene in Korea has remained relatively unexplored in the West despite its vibrancy during the last two decades. Throughout the 1980s, Korean artists became increasingly exposed to international art trends. With the proliferation of world-wide exhibitions and biennials in the 1990s, they increasingly began to travel, live, and exhibit abroad. While learning to communicate deftly in an international visual language, Korean artists also respond to their own personal experiences and their work reflects the culture out of which they emerged. The artists in Your Bright Future came of age amid political turmoil and increased freedoms in their small but increasingly prosperous country. Their experience has produced work that focuses, often humorously, on the ephemeral nature of life, time, and identity, as well as on the limitations of communication across languages, cultures, and generations. Each has made presence, absence, and change the center of their work.

Works by the only deceased artist, Bach Yiso, will be on view in the exhibition. Bahc’s work Your Bright Future (2002/2009) is a sculpture in which ten bright lights augmented by reflectors and connected by a flimsy wooden structure face upward, shining on a large white wall. The lights are anthropomorphic, recalling a crowd basking in the glory of a charismatic leader. It could be a wholesome scenario or the group could be in thrall to an autocratic leader. Bahc’s billboard We Are Happy (2004) is presented here as a banner with these words printed in white Korean script against an orange background. In the simplest and most direct way, We Are Happy (2004) questions what happiness is, and who is experiencing it. For LACMA’s exhibition, We Are Happy will hang at the museum’s Wilshire Boulevard entrance.

Other outdoor works include three site-specific installations by the artist renowned as the father of Korean pop art, Choi Jeong-Hwa. In Welcome, swaths of brightly covered fabric are stretched from roof to balustrade on the south and west facades of LACMA’s Ahmanson Building. Choi’s other two works are both titled HappyHappy and made of commercial plastic containers. In the BP Grand Entrance, thousands of these colorful items, procured from local 99¢ stores, are strung together, reaching from the ceiling almost to the floor. Choi’s other work is an interactive, educational project. Visitors are invited to make their own sculptures out of plastic containers and hang them on five chain-link fences situated on LACMA’s campus.

Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries is a Seoul-based collaborative that includes the Korean conceptual artist Young-Hae Chang and the American writer Marc Voge. Their works, made for the internet and as projections for gallery installations, combine words in different languages with their own sound compositions in Flash animations that pulse on the screen with great rapidity. For LACMA’s presentation, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries has created a two-part work for the galleries titled SUCKERDOM; PLEASE COME PLAY WITH ME, BABY and SUCKERDOM: PLEASE DON’T THANK ME, and one work for the web also titled SUCKERDOM.

Jooyeon Park, the youngest artist in the exhibition, also creates works that address language, using written words, as well as performance, video, photography, found objects, and sculpture to stress the fragility of existence. She believes language is an inadequate communication system and often creates works by jumbling found texts.

Gimhongsok and Jeon Joonho address South Korea’s place in the world, as well as the complex relationship among the U.S., North Korea, and South Korea. Gimhongsok’s video projection G5 (2004), features five Koreans singing a heartfelt rendition of the national anthem of one of the G5 countries (U.S., United Kingdom, France, Japan, Germany) in Korean. Though an initial response may be amusement at the discordance of hearing familiar, patriotic tunes sung in a foreign language, the question arises whether the singers are somehow subservient to the powerful nations whose songs they sing. In a more sober work, Jeon Joonho focuses on the division of North and South Korea in Statue of Brothers (2008–09), an installation inspired by a story taken from a famous public memorial of two brothers fighting on different sides of the Korean War.

Other artists in the exhibition examine the sociological effects of Korea’s rapid modernization. In his work, Do Ho Suh compares the formal languages of Eastern and Western architecture with the understanding that differences in architecture reveal different social structures. In 1994, Suh began making “fabric architecture,” using filmy, translucent textiles like silk and nylon to create ghostly and fragile renderings of his childhood home that evoke homesickness and the sense of loss. These works, often large-scale installations, meld seeming opposites, like the notions of inside and outside, personal and public, past and present. In Fallen Star, 1/5 (2008), Suh shows a violent collision involving a traditional Korean house and the building housing the first apartment the artist rented in the U.S.

Kim Beom questions Korean mass media in Untitled (News) (2002), for which he edited together numerous television news broadcasts in clips short enough to alter what the reporters were saying. Instead of reporting on events of the day, these familiar figures spout statements that vacillate between the inane and poignant. Using humor, the work questions whether the actual words of such television personalities are more enlightening than the ones that Kim has put in their mouths. Minouk Lim’s three-channel DVD projection Wrong Question (2006) records an anonymous taxi driver who does not understand the progressive elements of South Korean society, and conflates pro-democracy and pro communist factions. On the adjacent screen is Lim’s young daughter, who dreams of her mother staying home instead of leaving to work. Her grandfather instructs her instead to say, “I’ll be a great painter like Mom.” “What’s a painter?” the child asks. The two seem to be participating in different conversations—the products of radically divergent life experiences.

Kimsooja reflects upon gender issues from a uniquely Korean perspective. Early in her career, the use of sewing and traditional Korean textiles—usually associated with women’s work—allowed her to explore the role of family and nature of identity. Today she melds masculine and feminine qualities in the meditative video works for which she is best known. They record her performances on the streets of cities all over the world. In them, she is still, seen from the back, while oceans of humanity move around her.

The works of Haegue Yang and Koo Jeong-A address what lies on the periphery of everyday experience, impermanent traces of human existence, and the hidden or ephemeral. Yang’s Storage Piece (2004), is composed of crated and wrapped works by the artist. Unsold, the pieces were returned to her after an exhibition; with a show coming up and no space to store her old pieces, she decided to exhibit them wrapped. The work is amusing, but also rooted in a genuine complaint regarding the accumulation of artwork, which artists frequently cannot afford to store. Too often it takes over their studios—a reminder of the failure to sell. In conjunction with the exhibition, Yang will present performances concerning Storage Piece during the exhibition’s opening events and as part of a public program during the course of the show. Like Yang, Koo Jeong-A is concerned with easily overlooked objects and situations, frequently photographing mundane environments; creating drawings that are so minimal in their physicality that they become elusive; and installing tiny sculptures high on a wall or low in a corner.

Via (ArtDaily)