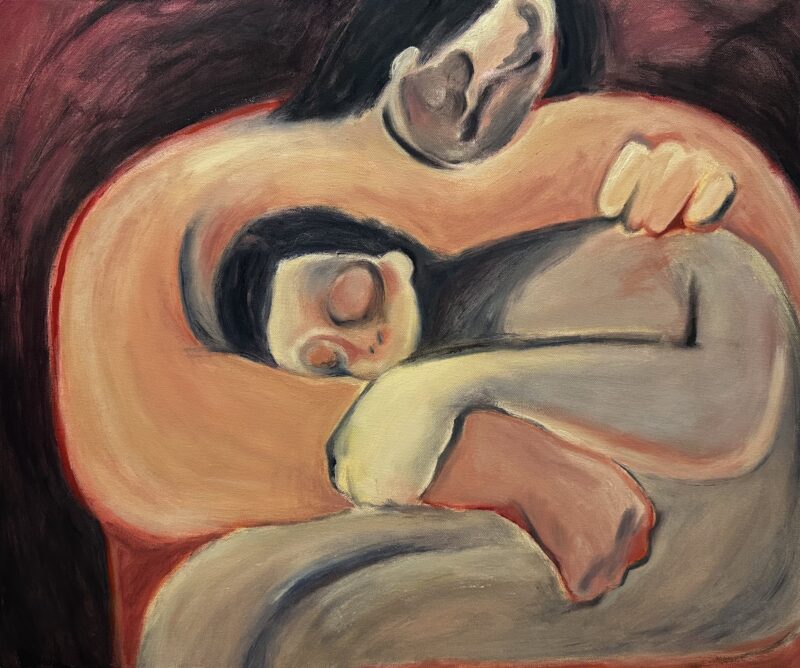

Italian London-based artist Bea Bonafini creates sumptuous immersive environments that hover on the border between functionality and objet d’art, craftsmanship and artistry. Inspired by confrontation in human relationships, Bonafini’s painterly objects, installations and textiles share a soft, luscious Art Deco palette and incorporate sensuous, tactile materials that invite viewers to get closer to the artworks as well as each other. Her work can currently be seen in London as part of the Zabludowicz Collection Invites series of solo exhibitions featuring UK-based artists without commercial gallery representation (on until 9th July 2017).

On the occasion of Bonafini’s current solo show, Marcelle Joseph probes the artist on the domestic and the decorative.

For your Zabludowicz Invites solo show, you have transformed the gallery space into a ‘quasi-domestic and non-religious chapel’, covering the floor with a large, patterned knit carpet and the walls with a drawing on tiles resembling an altarpiece and filling the space with an upholstered chair and a family heirloom. Tell me how the show came together for you and the inspirations behind it.

My initial point of departure was the characteristics of the Invites space. Formerly the side chapel of a Methodist church, its scale is long and narrow, with stained glass windows. I wanted to create site-specific work that wrapped around the architecture and stretched upwards in height, while assimilating the former ideology of the space. The works on show are a natural progression of my on-going research around the chapel as an installation space, where architecture and art collaborate to create a holistic experience for contemplation. The drawing shows a cave-like interior where terrazzo floors, pools of light and diagonal shadows of trees and totemic sculptures provide a space for reflection. The carpet piece takes a medieval Italian battle as a starting point; I found one in inlayed marble on the floors of the Siena cathedral, which are walked on and worn over time. I was interested in its double function as a walkable surface and carrier of a narrative image, which politically asserts a conflict. The horizontality of the image means that it can’t be seen in its entirety, and is absorbed through the feet. Considering the dichotomy of the chapel as nurturing while imbued with images of conflict, I wanted to create a link to the domestic environment, where nurture and conflict can coexist. British culture sees carpet as a vital domestic element. The technique I used is similar to inlayed marble, as the process involves cutting and interlocking many individual pieces to create a new image, which also happens in the drawing. A chair carved out of wood acts as a presence in the room; it is the essential domestic furniture piece, while alluding to the magic and comicality of thrones, seldomly used and reserved for figures of power during rituals.

You really played with scale in this exhibition – a wall-to-wall carpet filling every square inch of the exhibition space, a tiny silk pillow in the corner and a dainty but outsized upholstered chair fit for an eight-foot giant. It feels super immersive, as if the viewer is stuck in the set of a Disney animated movie like Beauty and the Beast. How did you look at scale for this show? Is there a conceptual layer to the work that is important to you or is it more of a formalist choice?

Spaces of worship play a lot with scale. Often, these buildings are awe-inspiringly tall; their enormous ceilings are covered in frescoes that force us to look up to the skies; vast floor pieces engulf us; and their colossal sculptures of deities humble us. I am fascinated by spaces that are capable of swallowing us into their system of logic, signs, symbols and sensitivity. You’re right, there is definitely a fairy tale aspect to the work. Fairy tales are alter-realities where the oddest things are undisputed because they belong to a coherent system of codes. Like myths, I think they are often the subtlest and most accurate tools we have to illuminate certain truths and help us make sense of the world. Finding a balance between the conceptual and the formal is always really important for me. In the same way that a fairy tale creates an internal logic but remains inextricably linked to our world, I intend for my work to be its own environment that weaves history and research into its own coherent language. I look a lot at holistic spaces like Giotto’s Scrovegni chapel in Padua, Fortunato Depero’s house museum in Rovereto, or Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden house-sculpture in Tuscany. These are examples where concept and formalism proliferate obsessively in a single space, and how powerful this combination can be.

You have been making opulent knitted works that I view like ‘paintings’ since your days at the RCA, and they have been shown in a myriad of different ways – on the floor for this show, on the wall, covering a table, folded on a shelf. How did this way of making come about? And is the mode of display a critical part of your work?

I have a strong relationship to painting, which I hope transpires in my fabric works. They feel like extensions of painting that have lost the attachment to the wall and the rigidity of the stretcher. I enjoy the plurality of references and the flexibility of formal possibilities that comes by replacing paint with fabric. I spend a great deal of time thinking about the display and presentation of the work, which can completely change their reading. The flexibility of textile lends itself to so many different choices of display. Draping it over a shelf or laying it over the surface of a table alludes to a domestic environment; hanging it from vertical structures makes it more bodily; wrapping it around seating demands a direct contact with the body. The decision of how to place the works in dialogue with each other is equally important. When a coffee table is paired with a sofa, it is asking to be used, and when it is left isolated, it becomes more sculptural and aesthetic. I often decide the mode of display of individual pieces when responding to a specific space, so their reading might easily change from one show to the next. I prefer this way of working, as it’s as flexible as the medium itself.

For your recent solo show at FieldWorks Gallery in London entitled A World of One’s Own (20 April – 4 May 2017), you created a mimetic living space complete with a bed, chair and two tables set with crockery, all with anthropomorphic features that brought the objects to life. Even the picture on the wall had legs and the door had arms and hands with seven fingers. In the press release text, Woody Mellor wrote, “She is the architect, this is her interior, full of curious objects and images that want nothing more than to be shared.” How paramount is it for viewers to activate your artworks? And which is more important – the physical activation through touching or intimate observation or the psychological activation? Viewers creating memories and associations of their own…

I like to think of my artworks as objects that crave intimacy, while having a life of their own, beyond the viewer. I often use sensuous materials or functional objects that can persuade us to spend time to grow familiar with them. The carpet piece in my Zabludowicz show has an abundance of subtle imagery that can only emerge after some time. The softness of its surface welcomes you to sit on it and get comfortable; through that process, the chaos of scattered animal and human limbs, and discarded batons and armour can begin to appear. As there is no separation between the architecture and the carpet, walking over it and activating it is a prerequisite for entering the room. It demands something of you as soon as you encounter it, and a gesture as simple as removing your shoes invites you to adopt a new mindset. Sitting with or on a work is one way to increase intimate observation. Using elements of domesticity is a way for me to activate the sort of behaviours and memories associated to a safe environment like a home. This and the use of seductive materials are mechanisms to disarm in order to render digestible the complexities of the works’ imagery and concepts.

For your degree show from the Royal College of Art last year, you bravely chose to exhibit your work in the art school’s café area, filling it with bespoke tables, chairs and shelving units containing other textile, ceramic and wood objects as well as house plants poking out of a decoratively shaped hole in the wall. Viewers were confronted with a quandary – ‘Can I sit on this artwork? Can I place my coffee down on this table?’. Is this slippage important to the work as it hovers between being a functional object and an exquisite work of art?

All kinds of slippages are important in my work. I like the fluidity between mediums as much as I enjoy confusing function with pure aesthetics. With each piece or installation, I’m interested in shifting the dynamics of the way they are encountered. Installing work in a cafe space meant that I adopted a space with a prescribed function of consumption and social gathering. There was a collision of behaviour patterns around the artworks, and people could spend time with the work, not only observing and thinking, but also meeting other people, eating and drinking. The social aspect was a way to counteract the sterility of the white cube space, which doesn’t often encourage the social or comfortable consumption of art. For the same reason that my fabric pieces were hung loose, I’m interested in increasing the physical and psychological proximity between artworks and us.

One last question… Colour. Your palette is absolutely gorgeous. Where does it come from? Is it embedded with meaning? Is it steeped in history – art, design or otherwise – or is it a matter of your own aesthetic choices?

I think my palette goes through phases, which are often influenced by an environment that has had a strong impact on me. Three years ago, I used punchy reds inspired by the rituals and festivals I experienced in India, and a year ago, I rode the pink wave of the RCA studios and the domestic setting of my Villa Lena residency in Italy. The palette of my most recent work is an extension of the blues, greens and silvers from the surrounding landscape of my tree-top studio. There is little division between the exterior and interior, so the variety of plants and changing sky affects the current work at Zabludowicz Invites. By working on several pieces at once, I can also let the works influence each other, so that they can start making more demands of me, or taking some decisions themselves.

Links

Zabludowicz Collection Invites: Bea Bonafini, London (1 June – 9 July 2017): LINK

A World of One’s Own: Bea Bonatini, FieldWorks Gallery, London (20 April – 4 May 2017): LINK

Artist’s website: LINK

Captions

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of Zabludowicz Collection Invites: Bea Bonafini – Dovetail’s Nest, Zabludowicz Collection, London, 2017.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of Zabludowicz Collection Invites: Bea Bonafini – Dovetail’s Nest, Zabludowicz Collection, London, 2017.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of Zabludowicz Collection Invites: Bea Bonafini – Dovetail’s Nest, Zabludowicz Collection, London, 2017.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of RCA Degree Show 2016, London, 2016.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of A World of One’s Own: Bea Bonatini, FieldWorks Gallery, London, 2016.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of A World of One’s Own: Bea Bonatini, FieldWorks Gallery, London, 2016.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of A World of One’s Own: Bea Bonatini, FieldWorks Gallery, London, 2016.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of RCA Degree Show 2016, London, 2016.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of RCA Degree Show 2016, London, 2016.

- Bea Bonafini, installation view of RCA Degree Show 2016, London, 2016.

About the Artist

Bea Bonafini (b. 1990, Bonn, Germany) lives and works in London. She completed her BA at the Slade School of Fine Art, London in 2014 and her MA in Painting at the Royal College of Art, London in 2016. Selected recent exhibitions include: A World Of One’s Own (solo exhibition), Fieldworks Gallery, London (2017); Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour (On The Bedpost Overnight)?, J Hammond Projects, London (2017); The House of Penelope, Gallery 46, London (2017); Summer Blue, Lychee One Gallery, London (2016); At Home Salon: Double Acts, Marcelle Joseph Projects, London (2016); Full House, Le Cabinet Dentaire Gallery, Paris (2015); The Behaviour of Being, Cob Gallery, London (2015); 15th Cypriot Contemporary Dance Festival (commissioned performance), Limassol, Cyprus (2015); and Anthropophagi (two-person collaborative show with Paola De Ramos), 26 Greek Street, London (2013). Residencies include: Fieldworks Studio Residency, London (2017); Villa Lena Art Residency, Italy (2016); and The Beekeepers Art Residency in Portugal, in collaboration with curator Mia Pfeifer and Cob Gallery London (2015).