At the Photoworks Weekender in Brighton, I saw Felicity Hammond’s work, which explores AI and data harvesting to create images. I began to wonder if image-making might be the primary way we channel these rapid technological developments.

Then I saw that Rankin had finally launched his 3D photographic sculptural project!

Full disclosure: I’ve known Rankin for a long time, and I’ve seen him put his creative work on hold more than once to focus on business/ finance etc. But was this full steam ahead now? Was he ready to unleash the full force of his creativity? I had to find out…

We know you have been working on this work for a while. What made you push the button on it?

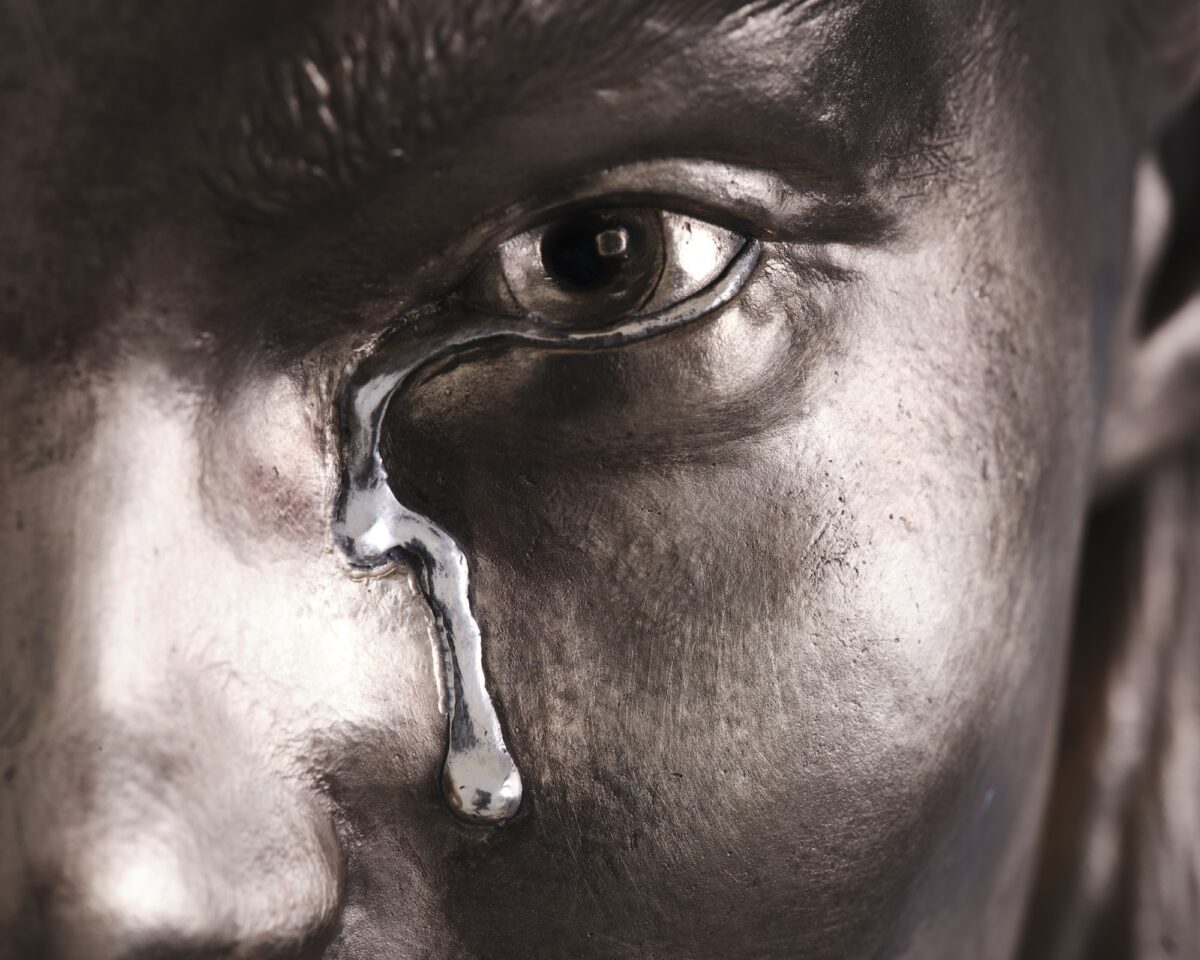

I had this realisation that photogrammetry and 3D sculpture offered a way to kick my work up a gear. In the past, I used practical effects and Photoshop to blur that line between reality and fantasy. Basically, whether it was creating a picture of a model on fire, or somebody’s face melting, I’ve always really enjoyed playing with the line between reality and seductive images.

Plus I’ve always been intrigued by how to move beyond photography, which is kind of how I ended up in publishing and filmmaking. Plus I think all photographers are kind of obsessed with sculptures, as they are almost a space beyond us ‘two-dimensional image creators’. But it was after a conversation with Damien Hirst, where he introduced me to photogrammetry, that I saw the potential to push all the ideas I have into a new realm. It allowed me to capture people in 360 degrees and create something that wasn’t just a photograph but a physical object, made from photographs. Something that would also stand the test of time. It just felt like the natural next step.

Who are they, what are you trying to achieve/say”

What really clicked for me was combining this technology with playful influences, like those AI apps where kids turn themselves into cats, aliens and even monsters.

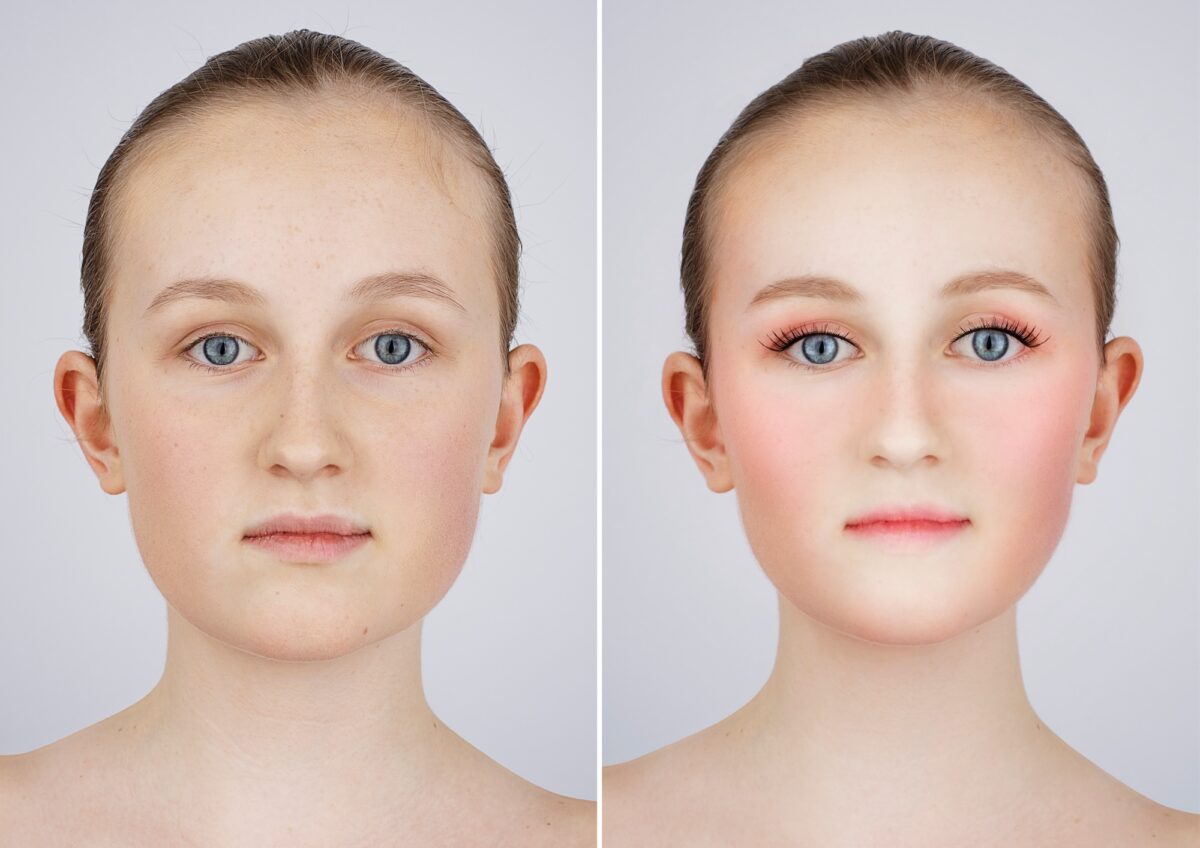

I’ve been playing with those apps for years, exploring them, which can be fun and very addictive. In fact my project “Selfie Harm’ came from examining and experimenting with those apps; which is essentially a project about handing a professional-level photoshop into the hands and minds of pre-teen and teen kids.

So, that theme of transformation fits perfectly with what I’ve always been drawn to – the idea of reshaping reality or distorting it. It allowed me to push what I do as portraiture and explore people in a more exaggerated way. It means I’m not just capturing the surface but I’m actually able to create something fantastical, almost mythical, about them. The ability to physically manifest those ideas into a sculpture just brought a whole new layer that I hadn’t been able to achieve before.

From there the idea for the series “Little Monsters” was a logical next step. This first piece is a model I love to work with Ellen Burton, and I’ve been calling it “Filtered Devil” because the horns are based on a Snapchat devil filter. The aim of the project is to get together a group of young models, along with the kids of some of my models or famous subjects from the 90’s/2000’s. I’m thinking of the project as kind of an exploration of their youth, public perception/presentation and also that punk attitude which you can only have when you’re in your 20s.

Do you see this work as an extension of your photographic practice?

Absolutely. It’s very much an extension of my photographic practice. I am still freezing a moment like a photograph, but with nearly 200 cameras at once.

They actually call them captures in photogrammetry, so I’m “capturing” the person from all of those different perspectives and rendering them as a digital 3d construction which becomes the final bronze. That means that the process starts as photography but ends up as something tactile from those captures. It’s pretty amazing.

It’s really cool for me because I’m still working with composition, and perspective, but now I’m bringing those elements into a tangible space. With photogrammetry, I can turn that moment into something permanent, a sculpture that carries my images into a form that can last for generations. For me, it redefines what photography can be – something that’s not just about time, but also about space and longevity.

One of the funniest moments in creating this sculpture was when the team at Pangolin initially smoothed out the skin in the first draft. I had to go back and tell them to fix it. I wanted the raw texture, the goosebumps, the imperfections that make us human. When I’m shooting for some brands I can get asked to hide those flaws, in the commercial world it’s all about an idealised version of reality. With these sculptures, I wanted to go in completely the opposite direction and capture the true essence of the subject. I think it’s those tiny details that bring my work to life, making it feel real and human.

There seems to be a real correlation between your practice and Warhol’s—the fascination with image, the use of new cutting-edge technology (screen printing with Warhol, etc.) and also the embrace of commerce (thinking about Swag here). Is he an artist who inspires you?

Wow, that’s an incredible compliment, thank you… I wish.

It’s funny, because when I was growing up Warhol was a hero of mine. It’s kind of naff to say it now, however I really believe that Warhol’s influence on most visual artists is undeniable. His obsession with image, celebrity, and the role of commerce in art definitely resonated with me when I first started. In fact Jefferson and I based a lot of what our magazine Dazed & Confused was at the beginning, on his 70’s magazine Interview.

What I always really loved about him was that he blurred the line between high art and popular culture, and I think that’s something I really aspired to too. I guess I also kind of loved that he seemed fearless in trying new things and just leaning in to “making” art.

In my work, it’s always been about capturing that one moment, that essence of someone or something. The practical side – whether it’s using a hundred cameras in a photogrammetry rig or a single lens – still comes down to the same thing: distilling a fraction of a second into a capsule, that lasts through time.

Warhol showed that imagery can become a symbol, a piece of cultural currency, and I feel like that’s what I’m chasing.

Are people or will people be able to commission these sculptural photographic portraits from you?

Yes, that’s the plan. I think there’s something incredibly personal and intimate about these pieces – each one is a unique, tangible embodiment of a person or a concept and I want to open up that possibility for commissions.

Imagine being able to have a photographic portrait that you can hold, touch, and display in a completely different way – something that can live on for hundreds, even thousands, of years. I think there’s a real appetite for that kind of permanence, especially in a world where so much of what we create is digital and fleeting.

Final question – will we be able to see this work in the flesh soon?

Yes, definitely, I’m planning on showcasing this and other pieces in an exhibition soon. The whole idea is to take photography beyond just being something you view on a screen or on a wall – it’s about creating something physical, something you can walk around and experience from every angle.

To go back to your first question, on reflection, it has taken so long for me to finish this piece of work mainly because I’ve been doing other things, I’ve been distracted. Plus of course, the process is quite drawn out, but now my focus and attention is on what I really love, creating art. Whether that is taking photographs or making sculptures, it’s a gift to do what you love and thankfully I’ve realised that over the last few months. TBH it’s what I should have been doing all along and funnily enough it’s what you’ve been saying to me all along!

FOLLOW: @rankinarchive