This week between packing boxes, moving out of Whitechapel and traveling I wasn’t able to catch up with London’s current shows but thankfully Berlin was saturated with great ones. Whilst I could delve into the Berlin Biennale at KW I thought that the more interesting thread to tackle was that running from Gropius Bau’s Ana Mendieta and Philippe Parreno to Fleisch at the Altes Museum.

As we drank our coffees outside Gropius Bau, we stopped to notice that several of Parreno’s fish were eagerly moving towards the orange tinted windows, poking – as if trying to escape into the world at large. The sight plunged us into a state of magical realism. Parreno, who invaded the Tate’s tanks with fish only last year and whose Ghost in the Shell is currently on loop, creates a curious haunted house for his first solo show in Berlin – one in which whispers and thunders echo from room to room, making us question the reality of the walls around us, causing us to inadvertently walk with caution.

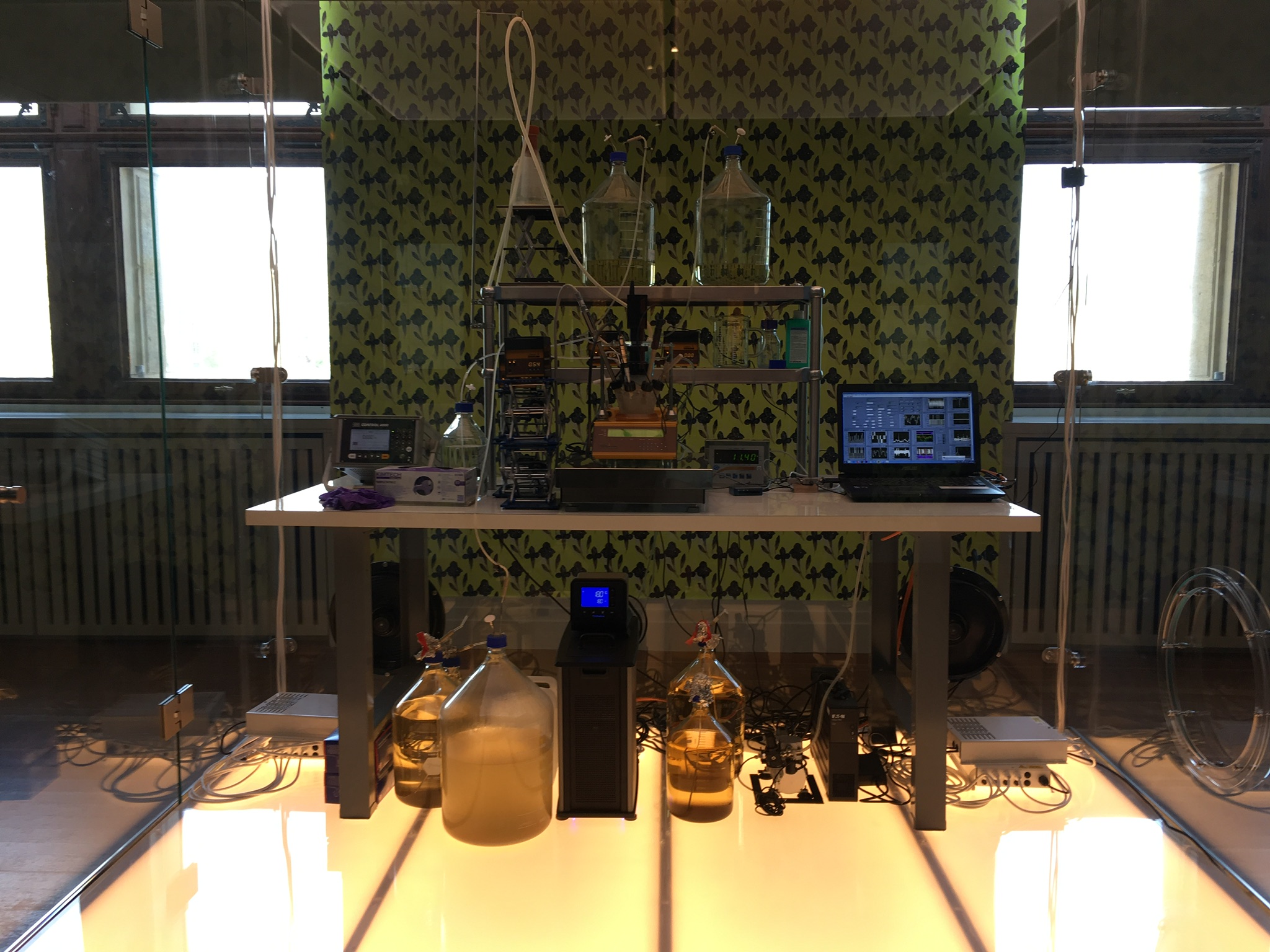

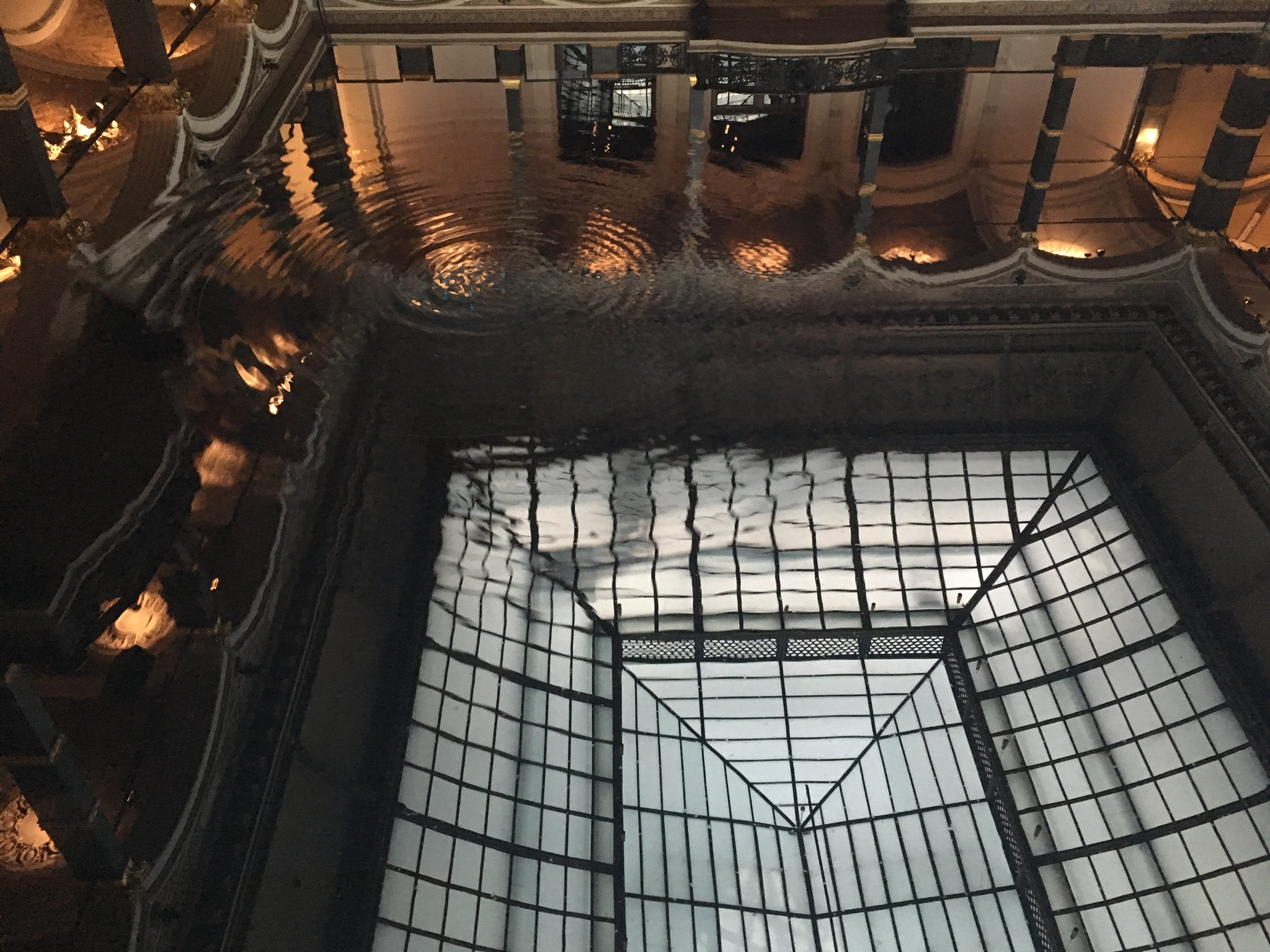

The house is set up like a Roman domus – with a rectangular pool in the middle containing water whose viscosity is noticeably different, and from which occasional bubbles emerge. Breath, and by association, life, streams through the elements, the walls, the furniture that makes up the show. As we sit and rotate besides the pool, we start to feel by the forces around us, less able to control what is to come. The orange aquarium where we find fish floating amongst us leads to a single room with a piano. A similar configuration is found at the opposite corner of the domus, although the differences between the two create a sense of unease and distrust in the objects themselves. A lab, with green patterned walls, is self-fuelled by yeast whose reactions control sequences of the show, as Parreno relinquishes further control to his medium.

Drawn by a flickering bulb placed above a vestibule we find ourselves within a dark room, observing a crowd – itself gazing above at the natural phenomena before them. We only witness it and perceive it through their bodies – flashes making their faces glisten. The video has no sound and ends with a larger flash – revealing the beauty of the frescoed room we were sitting in. Further down the corridor we find yet another flickering bulb. This time, although we instinctively position ourselves facing the pitch black screen, there is no visual stimulation. The thundering sound, turning into a more delicate rain, then into a drone melody (Daniel Avery – I thought of you) – it soon becomes clear – is what the crowd in the previous projection had been witnessing.

If Parreno uses interacting media to create the illusion of a breathing house – one whose body we are exploring from within – in the floor above Ana Mendieta uses her own body to draw our attention to the natural and original connection we have with nature. This isn’t animism, rather, it marks a return to our freer, less constrained selves. No photography was allowed so I had to resort to press images.

Mendieta was well known in the 1970s and 1980s for her performances, drawings and sculptures but it wasn’t until Galerie Lelong’s exhibition in 2016 that many of her video works – found posthumously – were restored and shown to the public. In ‘Covered in Time and History’ we became privy to 23 of these restored and digitised Super 8 pieces.

Ana Mendieta, Creek, 1974 © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC.,Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

The set-up of the show was intentionally bare – dim lighting, dark walls allowed our eyes to focus on the small screens before us (unlike the larger projection screens increasingly prevalent in video art pieces). Whilst I appreciated the videos having a time lag between them, so that black screens would intermittently appear, reminiscent of eye lids opening after a brief slumber, the white credits flashing were unnecessary and distracting seeing as they introduced the element of text where it was unwarranted.

Installation view © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC.,Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Foto: Mathias Völzke.

In the first room, we find Mendieta first drawing parallels between the fire before us and our act of copulation in Volcan and in the Silueta Series. We then stand before Burial Pyramid observing a series of rocks oscillating, breathing, until, limb by limb, we notice that Mendieta’s body lies beneath them. This marks the start of what will be her distinctive appearances and disappearances into the earth.

In the first room, we find Mendieta first drawing parallels between the fire before us and our act of copulation in Volcan and in the Silueta Series. We then stand before Burial Pyramid observing a series of rocks oscillating, breathing, until, limb by limb, we notice that Mendieta’s body lies beneath them. This marks the start of what will be her distinctive appearances and disappearances into the earth. As we walk through Room 2, whose focus is Mendieta’s repetitive use of blood, we increasingly think about her tragic death and continue to do so throughout the show.

Yet, as we find Mendieta’s silhouettes traced in white paint, in red, with fire, smoke, in sand – as we see her bury herself, hide amongst the Iowan or Mexican landscape, appearing in a mirror – an incantation is cast. The recurring figurine and Mendieta herself become interchangeable and as the silhouette is marked on every conceivable element Mendieta truly is at one with the earth as she most desired to be and moves us to carve further ones, perhaps in landscapes she had not travelled to – allowing her to do so now.

Ana Mendieta, Sweating Blood, 1973, Super 8 Film, Farbe, ohne Ton.

© The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC.,Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

Parreno and Mendieta consider the body and its relationship with the elements, be it by allowing it to be astounded by phenomena and reactions we can’t quite follow or by returning it to its natural roots – the shell we carry, made out of flesh, is intentionally prevaricated by the Earth’s forces or haunted by animated surroundings.

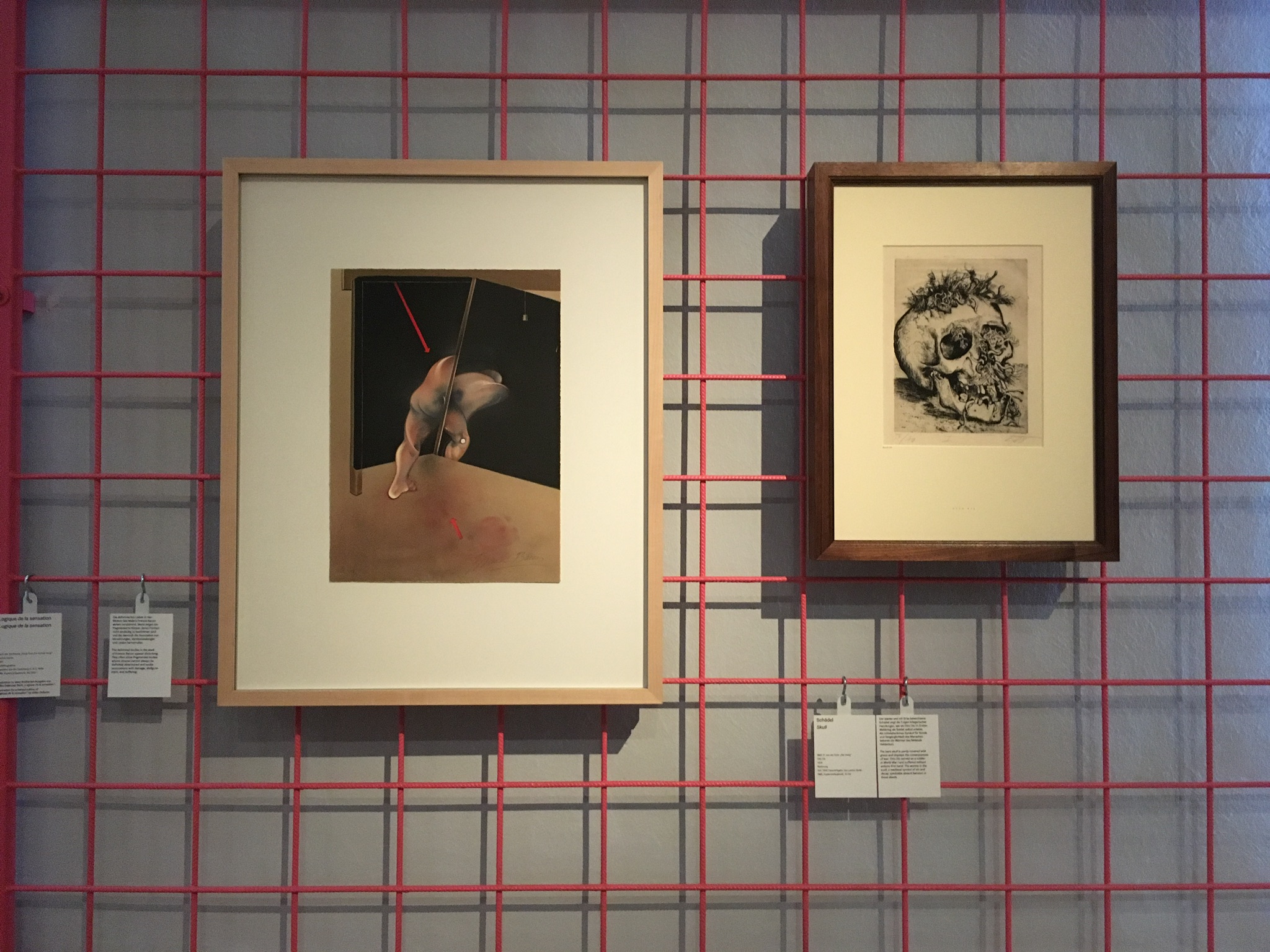

At the Altes Museum however, we bring our attention to Fleisch, or meat, in its various incarnations. I originally thought the show would span several rooms but upon waking into the single space, with red grids captioning the hanging works, I felt like I had walked into a school project. The aim of the Altes Museum was to create an inter-thematic display of objects from the Staaliche Museen zu Berlin’s collections, juxtaposing these to illustrate the relationships we have with flesh.

Although I do maintain that the red grid and cases were perhaps too reminiscent of a school presentation, the works on show were pleasantly impressive. The single room worked well in avoiding a thematic divide meaning we could walk from the intellectualisation of flesh, to carnal desire, to its religious associations and its commodification quite freely.

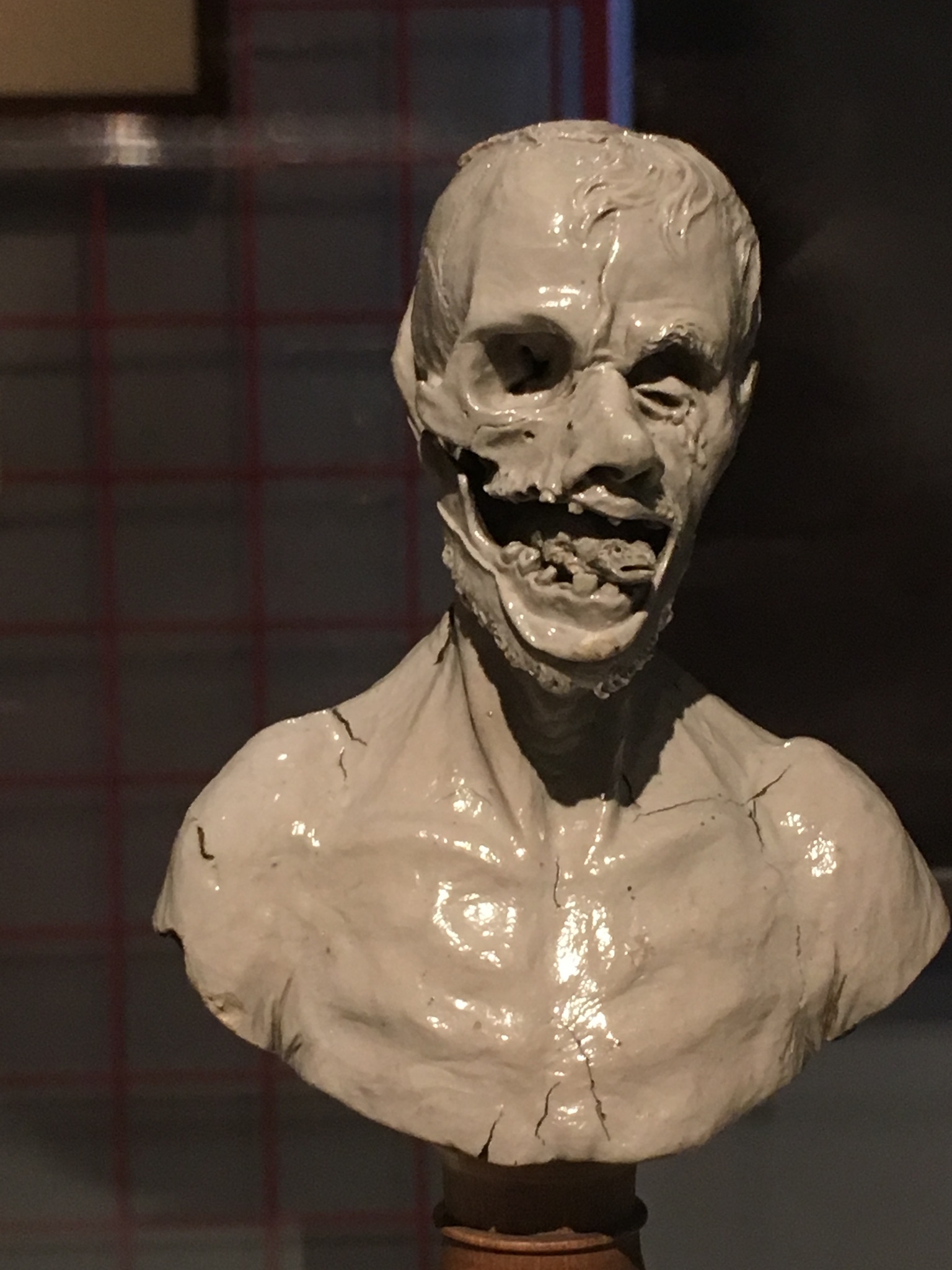

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s etchings were an undisputed highlight, as was The Hunt by Christian Jankowski in which the protagonist enters a supermarket armed with arch and bow and hunts for eggs, cereals, washing powder to the confused reactions of fellow customers. Alexander Enger’s Auf dem Fleischhof Lüneburger Straße in Moabit photographing a butcher or Johann Christoph Ludwig von Lücke’s bust were placed amongst Roman phallic figurines, Greek vases with orgiastic scenes and more innocent piggy banks.

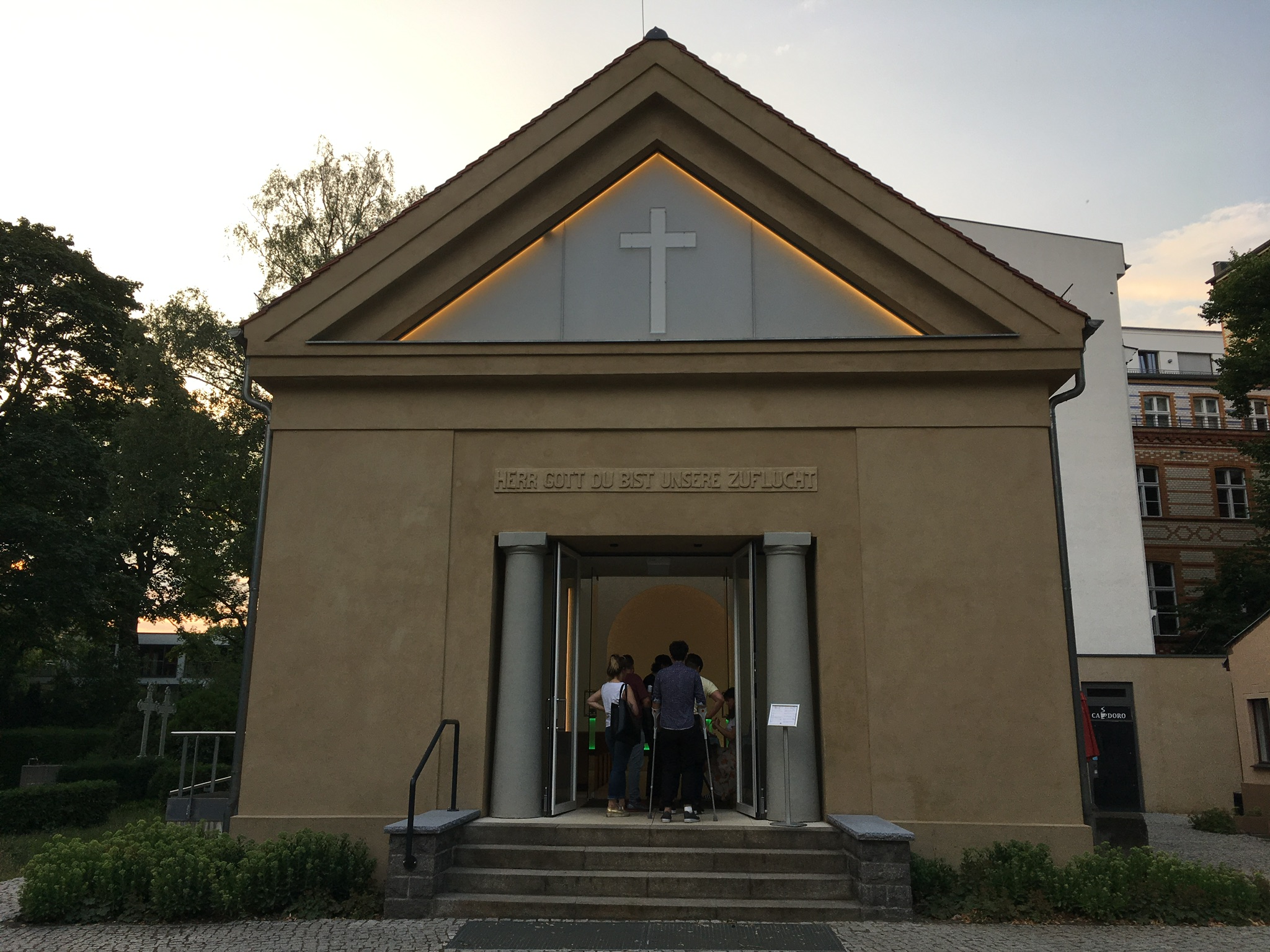

We left our exploration of the body and eventually made our way to the Dorotheenstädtischen Friedhof I.

There, in the funeral chapel, a James Turrell installation loops amongst its silent surroundings. The corporeal is abandoned we enter a liminal space – made sacred, regardless of individual beliefs, by Turrell’s transcendental light graduations. Those visiting should note that there are a few rules to follow: no photos or videos are allowed as per Turrell’s wishes, no walking behind the altar as the chapel is used for functions, no touching the glass windows and finally no talking as the space is intended to be meditative. Unfortunately the visitors we were with seemed not to be able to follow very simple directions and this tainted our experience. Despite their extremely disrespectful behaviour, the installation is stunning in its quiet beauty.

As the sun sets, hues shift ever so slightly causing us to believe the initially white candle stick has turned green amongst a lilac backdrop. Our sense of depth is altered, and we sit on the wooden pews not wanting to ever leave, enchanted, in a trance.

Philippe Parreno was at Martin Gropius Bau from 25 May to 5 August 2018

Ana Mendieta was at Martin Gropius Bau from 20 April to 22 July 2018

Fleisch is at the Altes Museum until 31 August 2018

James Turrell’s installation is permanently on at Dorotheenstädtischen Friedhof I