Emma Cousin, Heroes, 2017, oil on hessian, 100 x 100 cm.

Emma Cousin is a British artist, curator, writer and poet whose humorous and surreal works on canvas and paper have already featured in London in two group shows, a solo show and a two-person show in the first two months of 2017. Her work can currently be seen in group shows at The House of St Barnabas in Soho until 5th July 2017 and at Transition Gallery in Hackney until 4th March. Legs are the subject matter of choice of Cousin’s oeuvre that examines the human condition and the history of painting through a mixture of figurative and geometric elements rendered in a distinctively painterly style using a bold colour palette and with particular attention to the symbolic meaning of the visual forms depicted in her work.

So let’s talk about legs… You have been painting and drawing legs for the last few years. You have spoken about these body parts representing a visual vocabulary of sorts. Can you explain more about your use of this representational motif in your work?

The leg represents a stand-in for humans that we can all relate to and ‘read’. Its value is its agency; it implies movement and effect. Linguistically, there are wonderful wordplays originating from it that stoke powerful imagery and humour when taken literally ‘leg up, leg over, legless’ and highlight the complexity and absurdities of our semiotics. As a repeatable element, the leg provides a unit in which to explore the formal concerns of paint- the ground vs the ground we stand on, the weight, the form, pattern and so on.

There is also the tension between corporeal presence and absence of a fragment. A limb/a leg. This also suggests vulnerability – perhaps fragment as representative of part or whole in a process of substitution. And something unique and multiple which nods to identity. And a part of a social engagement, society as a whole.

As such, the leg offers a structure:

- to ‘build’ a painting with (thinking about our brief parallel to systems painters);

- a representational device for humans and social behaviour reflection (links to how we are with one another but also how we live and fit in, in terms of space and architecture); and

- a system through which to think about paint on the support, which is the canvas/wall/frame/gallery/geometry.

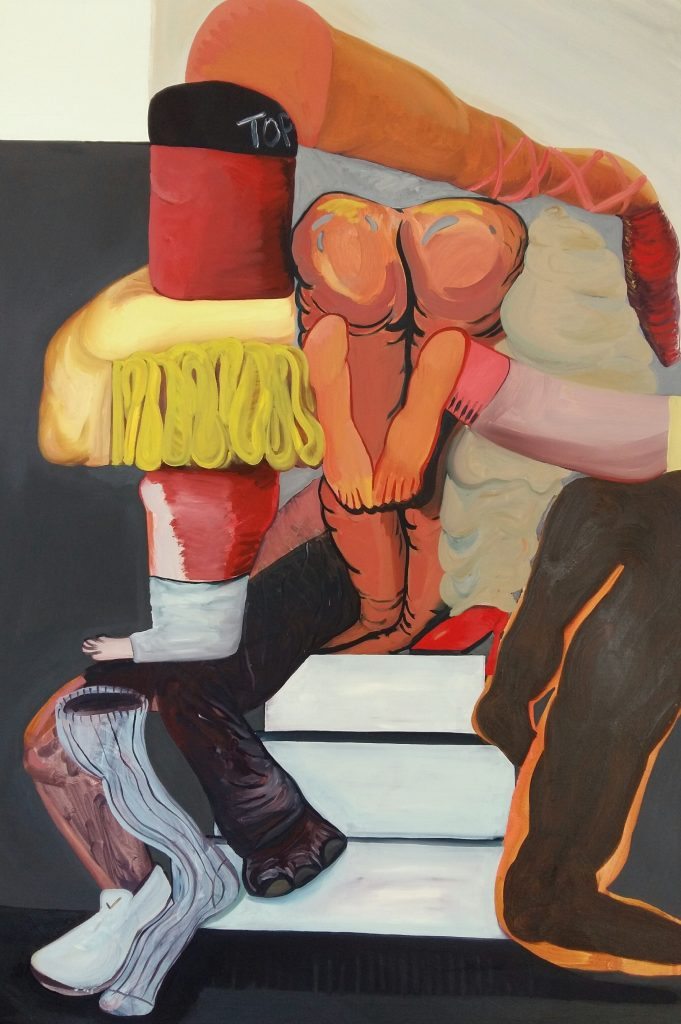

Emma Cousin, Ugly contest, 2016, oil on canvas, 140 x 100 cm.

Emma Cousin, Ugly contest, 2016, oil on canvas, 140 x 100 cm.

You were the artist in residence in Painting at the Wimbledon College of Arts last autumn. What did this residency entail? From your blog, it looks like you collected all sorts of photographs of, artworks related to and poems about legs as well as hosting a programme of workshops, film screenings and talks. You presented a solo show of the work and research from this residency in February at the Delta House Gallery. What did you present and do you think this residency will foster any shifts or new developments in your painting practice?

The residency involved being immersed in a studio within the student studios with an open door policy. I encouraged this by asking the students or anyone that saw the poster (staff etc.) to ‘bring me a leg’ which I built into a body of research alongside my own that was pinned to one wall of my ‘in situ’ studio. In exchange I gave them a banana — emphasising the possibilities of liquidity and exchange that aren’t based on capitalism. I also invited my peers to post or make or send me responses remotely, like writings from Louise Ashcroft and Paul Carey-Kent. I added the ballast of my existing ‘language’ with drawings, collages, cut outs, line sketches and found things. It grew organically and humorously, enabling me to step back and take stock of all the ‘chapters’ involved in order to view the complexity of the stand-in — all the things the leg could evoke, embrace, engage and refer to or represent.

At the the same time, I put together a series of workshops that ran weekly throughout the residency to think about our messed up semiotics as humans – i.e., language, sign, symbol, image, allegory, inherited information and so on. For example, one workshop was on the body and gesture, thinking about recent politics, stances and language. I invited the brilliant artist Holly Slingsby to develop this workshop. We used contemporary dance and performance techniques to guide playful games to think about our stance as young artists and how we can use what we have around us to assert or investigate this position. We also held discussions on how to sustain artists’ practices post-study, which is a demonstrative aspect of the artist in residence.

Alongside this, I gave a few full days of tutorials, which I loved, and was one of the best aspects of the residency. These exchanges inspired a series of paintings about the balance between fear and thirst for knowledge that the students currently there seem to embody absolutely. Bananas also feature in some of them (!) and Morandi who is increasingly important to me.

The library was a real treat and a chance to explore my increasing interest in dance and the body through theory and fashion history. Access to the foundry and print facilities meant I could play myself and realise a series of bronze ‘trophies’, which are a very exciting development. The materiality of the foundry excited me too, and I would like to work further with silicon and shellac which I learnt how to use. Drew, the technician there, is exceptional and very patient!

Essentially, it allowed me to zoom in and then out and then in again and see the body of work as a whole in order to see where it could go next. It also provided the room and support to collate all the research (drawings, writing, painting, etc.) together, which has formed a book called Legwork, which is what I called the residency. It is a sort of visual and verbal exploration of the leg language and its evolution. The book will be launched at my solo exhibition, ‘Sick Little Monkeys’, featuring basic video and sound, wallpaper, paintings, the trophies and possibly a carpet of legs that I’ve made..!

That was a long answer but it was a very dense time!

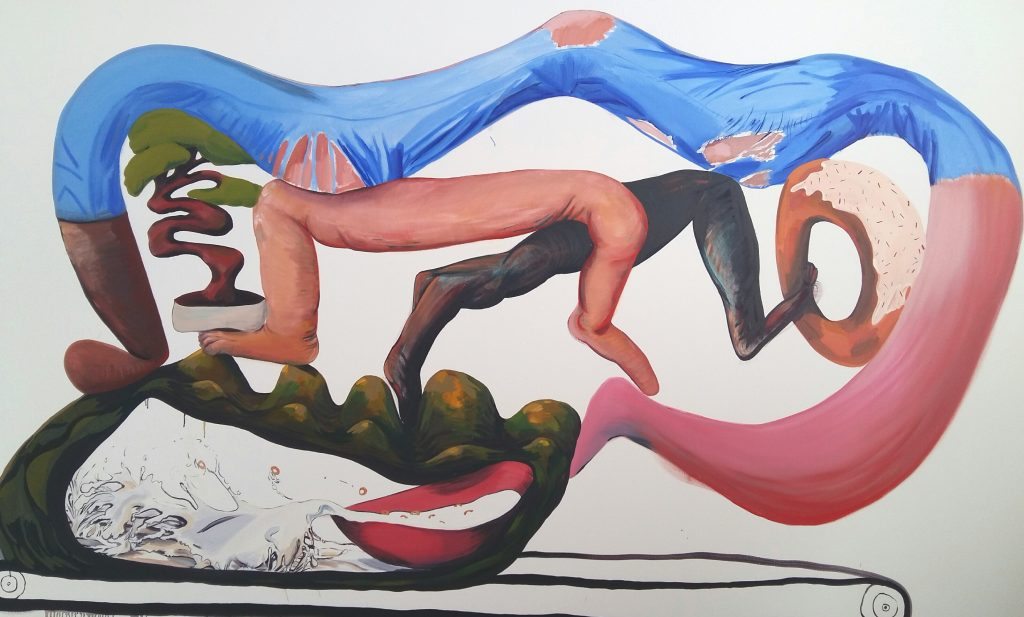

Emma Cousin, Keeping in shape, 2016, oil on canvas, 120 x 160 cm.

For the group show EARS FOR THE EYES curated by Paul Carey-Kent at Transition Gallery (10 February – 4 March 2017), you are presenting a painting entitled “Falling on Deaf Ears” as well as a poem entitled “Hearing aids”. How does writing and poetry fit into or inform your practice?

They are essentially parallel forms of exploring our semiotics as human, visual and linguistic, and using both sets up the opportunity to make unexpected and often numerous connections and to explore the depth of an image, sign or idea. ‘Falling on deaf ears’ was the phrase that inspired both the work and the writing. This phrase originally came from a drawing I made ages ago with this title. Observing my grandparents fuelled the poem ‘hearing aids’. That writing then gave me some missing information for the painting, such as palette and emotion, though the physicality (painting style and composition) had been drawn from the initial word play, ‘falling on deaf ears’. I often like to think of these absurd statements literally and use a visual form to see what happens. It’s a fun way to start a painting. This one was slow though as it seemed like I had to write the poem to resolve the painting and then revisit and edit the poem again. It’s a constant to and fro and at the time, the writing and the painting seem like two different things. I think that the brain and its inherited semiotics make the connections intuitively first. Sometimes, there are poems with no paintings, often in fact. And vice versa. The real link is that both are ways of looking, reflecting and understanding.

Emma Cousin, Falling on deaf ears, 2017, oil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm.

In 2015, you founded and organised the exhibition programme for a year-long project space in your gutted and soon to be refurbished home in Brockley called Bread and Jam, working with over 100 artists during that period. What were some of the highlights of that project and did this curatorial experience have any spill-over into your own practice?

The highlights have to be the artworks. And the social aspects – the performances, readings, workshops, the library – that all reached out to the public in an audience ranging from House and Garden magazine to our neighbours and their kids! Watching the shows evolve and trying to work organically with them to guide and gently curate something cohesive whilst remaining true to our ethos of play and experimentation was very challenging and exciting. I learnt that if you ask for help and the project is interesting, people generally say yes! The baker, Coopers Bakehouse, that I contacted sponsored every show from the start with free warm loaves of bread cycled round on the eve of the private view. So we could feed everyone that came to see a show. Again, this was an important social element. Over the course of the programme, we showed a video by a seventeen year old, showed a piece which went on to be shown at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, housed poisonous flowers in a sculptural installation that featured milk (Miriam Austin) and premiered sound pieces by established artists. It was a rollercoaster of learning and creativity and fun and chaos and collaboration. I remain indebted to Emily Austin and Rebecca Glover for supporting my initial idea and working with me to realise it. They remain good friends and Emily and I continue to collaborate. This is a precious outcome of the project. I have also gained confidence and feel less fearful. The worst that can happen is that is doesn’t happen at all.

Hermione Allsopp, installation view at Bread and Jam I, London, 2015.

Hermione Allsopp, installation view at Bread and Jam I, London, 2015.

You co-curated a wonderfully researched and presented group show called “It’s Offal” in December 2016 at ArthouSE1 in London, featuring historic as well as contemporary artworks by 29 artists, from Hermann Nitsch, Piero Manzoni and Helen Chadwick to early career artists such as Nils Alix-Tabling, Jane Hayes Greenwood and Nicholas Hatfull, exploring what lies within – from excrement to innards. How did this show come about and what inspired the curatorial theme?

Well, firstly thank you!

Ha! This is funny as the real answer is the food itself, offal! Emily (Austin, a brilliant collaborator) and I ate a lot of offal at Bread and Jam before the invigilating started on the weekend (the benefit of living in the show is that you can cook for and eat with everyone all the time! This became a massive part of Bread and Jam). So we just started talking about it and why we loved it so much and assessed the reaction this habit received from other artists. It raised questions on value at the beginning, what we throw away (offal comes from abfall which means throw away), which is one of my concerns in my work. Quickly, it became a discussion about the body, one of my rooted interests, and I liked the fact it made me think about the ‘bodily’ nature of painting, the materiality of the stuff. As a student at the Ruskin, we had fab lectures on Gina Pane and Marina Abramovic whom I became a little obsessed with so when we revisited these women and their actions in the history books and through private collections and found that the contemporary rhetoric has morphed into a new territory, it spiked our interest. We researched the show for eight months, focusing on exploring the theme as fully as possible, talking to people, visiting greasy spoons and eating liver and gravy, interviewing older people who had different notions of its value, reading about beauty and ugliness, pleasure and repulsion, innards and excrement and discussing the idea with other artists. In the end, the show was pretty expansive with 26 artists including 10 private loans, two new films and many contemporary works made for the show in response to the theme. We also commissioned two performance artists to make new work and they performed at the private view and symposium, where Patrick Brandon’s commissioned poems in response to the show were showcased. It was brilliant. It also shows you how long it takes to really put on a show on that level.

What’s next for you in 2017?

After a very busy start, I am happy to be back in the studio and in my painting routine again. I am currently working on a piece about looking at painting. Which is really, just about painting. What it’s for and why we do it or look at it. It’s hard. I am also re-reading as much John Berger as possible. My contemporary dance education, both physical and theoretical, also continues. I love it. And Emily and I are also planning and discussing two possible shows in the future. It’s going to be fun!

Artist’s website: emmacousin.com

EARS FOR THE EYES at Transition Gallery, London (until 4th March): LINK

Wimbledon College of Arts Residency: LINK

Bread and Jam Project Space: LINK

About the Artist

Emma Cousin graduated from the The Ruskin School of Art, Oxford in 2007. She was recently Artist in Residence in the BA Painting Studio at Wimbledon College of Art with a solo show of the work and research in February 2017 at the Delta House Gallery. Other recent selected shows include: Mudhook, a two-person show with Milly Peck at Tintype Gallery, London (2017); The Other Side, a group show at The House of St Barnabas, London (2017); Ears For The Eye, a group show at Transition Gallery, London (2017); The Marmite Painting Prize (in which she was runner-up), London and Ireland (2016); making the nature scene, The Tannery, London (2016); Seven Painters, a group show at Arcade Gallery, Cardiff (2016); Lucy in the Sky, Transition Gallery, London(2015); Luck and Chance and Foule Parliament, both touring group shows in 2015. Cousin was selected for the Lynn Painter Stainers Prize and shortlisted for the Anthology Prize, both in 2016. Emma Cousin and Emily Austin recently co-curated It’s Offal, at Arthouse1 Gallery, London (2016). Cousin also ran the curated project space Bread and Jam in her home in Brockley, London for a year in 2015-16.