Holly Hendry doesn’t do anything by halves. After graduating from the Royal College of Art in July 2016, her work has been exhibited at a group show commemorating The Royal Standard’s tenth anniversary in Liverpool (30 July – 11 September 2016), alongside more experienced practitioners such as Jonathan Baldock, David Blandy, Celia Hempton, Liliane Lijn and Jess Flood Paddock. Hendry’s work is currently on display at Kunstforeningen GL STRAND in Copenhagen at EXTRACT, an art prize exhibition presenting seven young rising stars newly graduated from art academies in Beijing, London and Copenhagen (21 January – 5 March 2017). Even bigger news is that a new body of sculptures by Hendry is the focus of a solo exhibition at the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, running until 24th September. And please look out for upcoming exhibitions of Hendry’s work at Limoncello, her new gallery in London.

Taking this splendid occasion to speak with Hendry, Marcelle Joseph attempts to get to the bottom of what drives Hendry’s materials-focused sculpture practice.

Congratulations on your solo show at the BALTIC that opened last week! Just reading through the materials you used for this show – jesmonite, plaster, foam, wood, steel and water-jet cut marble, I am exhausted… What drives your choice of materials?

Thank you! The materials you list originate from a long line of tests and collections as well as computer drawings (which I transfer into water-jet cut elements) and collected objects (which I remake in a different type of material). Most of the time, the material tests and the final forms come from an investigative process, where I’m trying to get closer to the characteristics of something; it’s specific qualities that make it what it is. For example, the marble cut elements relate to the ideas behind the work – a connection to the ground and compression of substances, layers of time and fragments and bodies. I’m interested in these sites of production where we mine these sort of materials from the ground, creating cavities in their absence, and the way they are primed and polished and finished to be used to coat the inside of homes, like a kitchen counter. I’ve cut some of these slabs into squiggly shapes that are inlaid into the work, and together they look like worms or the insides of our bodies, so it’s a lot to do with systems of regurgitation, of a cyclical nature, almost cannibalistic. It relates to bodies and things turning into stuff again, perhaps recounting Freud’s death drive where he says we desire to return to the indeterminacy of an inorganic state.

I have also used jesmonite combined with other materials to create textures made up from materials that exist around us – new types of composites that seem so far from archeology. They contain spat-out bits of chewing gum, soap, plastics, cosmetics, cat litter and fish tank rocks to name a few. These materials are agglomerates that form new types of stone from our environment, stuff that is circulating and accumulating with nowhere to go. The work itself is a lot to do with making and the making is very tied up in the thinking behind the work so it’s crammed with these details that have meaning to me, which are very tied to the materials they are made from.

Looking at your multi-layered luscious sculptures, for me, it is one-part wedding cake to two parts geological strata in pastel candy-coloured hues. How do you achieve this incredibly moreish effect? Could you describe your process and use of casting?

It’s a process of working back to front and inside out. The physical making is a combination of casting, pouring and fabricating which cohabit as one – lots of invented methods and material combinations. The layered sculptures begin with a negative mould – the crate – which dictates the shape of the work, as the materials are formed within this. For my Gut Feelings work, I have used the example of an endocast to help me speak about my making of and thinking about the work – an endocast being the internal cast of a hollow object. Natural endocasts, which are a type of fossil, are formed when the remains of an organism dissolve in the ground, and the remaining organism-shaped hole is later filled with other minerals and sediments in the internal cavity of that organism – creating a positive from the absent shell of the original object and a trace of something that existed. It’s about time and change but also the filling of a negative space – I think the endocast does a good job in encapsulating my interest in this membrane that surrounds us and other things, and points when these contours shift and morph, and turn inside of themselves.

Your works have a monumental, architectonic stature. When we first met, I found out that your father is an architect. Has that upbringing influenced your own art practice?

Yes he is – my whole family are very creative. I grew up in a house that my Dad designed and built with his friends, so space-making and building were part of my vocabulary from when I was young – seeing this hands-on experience of a living space emerge. I think there is an interesting relationship between the spaces you shape and build, and in return, how these come back to shape the way you live. I love the weird things that happen when you know a space so well – like the way that you can navigate it in complete darkness, purely through touch. So yes, these ideas of building big and taking on a space feel pretty natural to me in terms of making.

You often work in a site-specific fashion and make sculptures that explore different ways of containing and constructing space as if these inanimate objects were living, breathing organisms. Are you always thinking about contemporary society’s use of space when making your work?

I like to challenge these spaces, and this provides challenges for the work. My approach to space relates to edges, usually using the building as a skeletal container as the starting point. The works themselves also use architectural elements that refer to our use of space in a wider context. These forms mimic elements from design or public spaces as well as furniture or medical equipment – generalized body forms, inspired by the shape of things that are designed to fit our bodies like a sun lounger’s curves or the indents on a handle that show us where to grip – physical instructions for our bodies to fit to. We have lots of distractions that distract us from looking at architecture, and there are public devices to make us subconsciously move and live in certain ways. I think these devices are fascinating, as well as the function of the architecture itself, and its material makeup. So in a sense it’s what we’re not thinking about, that I like to think about.

In opposition to this, my approach to architecture is pretty physical; it’s an embrace where succulence and sensation are introduced into the sphere of architecture, which is usually bound by a more intellectual critique. I really enjoy this physical interaction. The spaces where I show my work are usually the solid frameworks or edges where more compulsive engagements and chunks of materials and processes can exist within, but it’s a real engagement between both things. These spaces seem to have the same role as the crates (or moulds) where my materials and layers are poured into – with fixed boundaries, but totally essential in the concept, production, display and form of the work.

Your use of colour is ingenious and is often grounded in a research-based conceptual framework. What inspired the colours for your BALTIC show?

Previous research has delved into the theory of institutional interiors and the effect of such colours on your physiology. The colours for the BALTIC show are similar to my more recent works in their slightly deadened candy coloured hues, but this show in particular uses colours more specific to medicine – the colours of the thermoplastics used to make splints and the minty green of scrubs – light blues, greens and purples. This might not be completely recognisable, but it is the origins of my choices. I have been looking at a lot of medical cross sections in my partner’s anatomy books, as well as cross sectional cuts in architecture and diagrams of ships, where the colours are used to name and divide.

There is also a cartoon element in their sweetness which I feel is important in relation to the murkier subject matter. I like the way that the colours evoke a reaction which targets the senses – through taste, smell or even touch – so combined with these ideas of digestion or decomposition, there becomes some strange implied cycle – material, mineral and vegetable breakdown and reformation- partially brought on by our relationship with the colours.

You embarked upon a yearlong residency at BALTIC 39 studios after winning the Woon Foundation Prize for Painting and Sculpture in 2013. What does it feel like to go back to Newcastle to show your work at the BALTIC? Can you give us a brief synopsis of the show?

Newcastle is an amazing and vibrant city and I am so pleased to be back up here showing work at BALTIC, it feels very important to me.

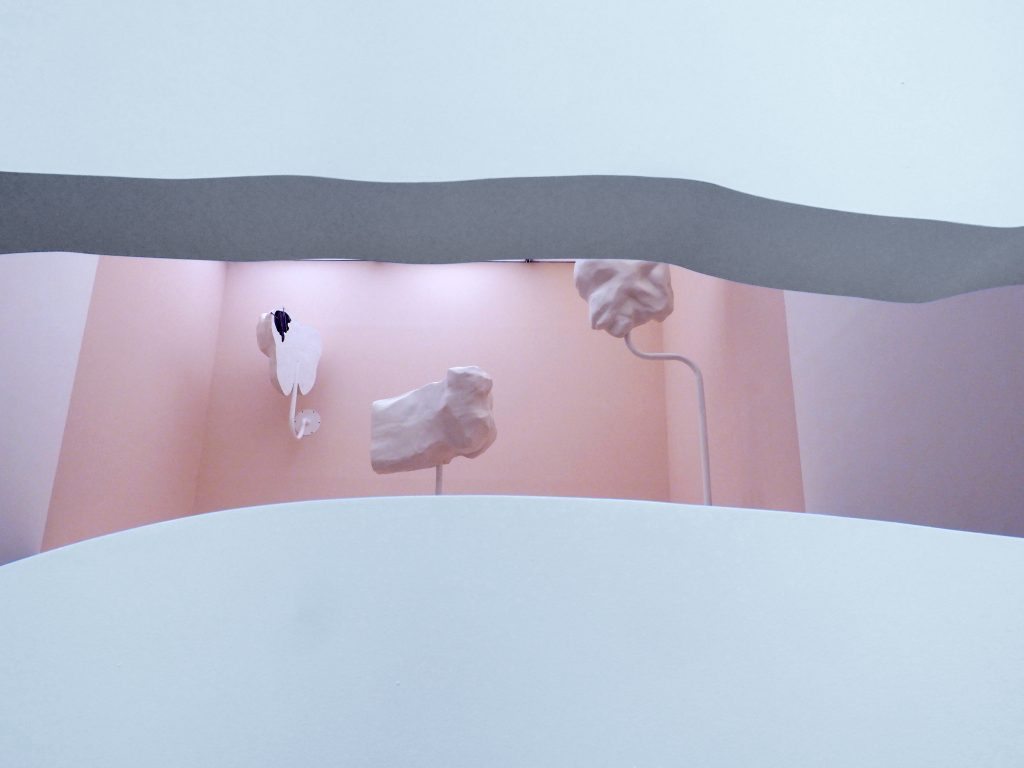

The exhibition brings together new works, which I’ve made for the level 2 space at BALTIC. There are variations of surfaces and planes, where holes are cut in walls and one section of the floor is almost extruded up to form a platform where toothy-boney sculptures tower above. There’s a shifting of macro and micro where people are brought up close to the forms that speak of the underneath – whether that is under our feet or under our skin. It’s a closer look at impressions of objects, bodies and ‘stuff’.

All photos: Holly Hendry, installation view of ‘Wrot’ at The Baltic Centre For Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2017. Photo: Mark Pinder/BALTIC. Courtesy of BALTIC and the artist.

EXTRACT at GL STRAND, Copenhagen (21 January – 5 March 2017): LINK

Wrot: Holly Hendry at Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead (18 February – 24 September 2017): LINK

Artist’s gallery website: LIMONCELLO

Artist’s website: LINK

About the Artist

Holly Hendry (b. 1990, based in London) gained her BA Fine Art at The Slade School of Fine Art (2013) and her MA Sculpture at the Royal College of Art (2016). Recent solo shows include those at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead (2017); Limoncello Cork Street, London (with Kate Owens); Rice + Toye, London (both 2016); Bosse & Baum, London (2015); The Oval, London; and Gallery North, Newcastle (both 2014). Recent group shows include Kunstforeningen GL Strand (2017); Copenhagen; VITRINE, London; The Royal Standard, Liverpool; CBS Gallery, Liverpool; Cowley Manor, Cotswolds (all 2016); Turf Project Space, Croydon; Chesterfield House, London; Salt + Powell, York (all 2015); S1 Artspace, Sheffield; and Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah (both 2014).