David Hockney wants to tell you a joke. A man goes to a doctor and informs him that he wants to live the longest life possible – what should he do? The doctor asks the man to list his vices and then he says: “Right, I want you to give up smoking, I want you to give up drinking, I want you to give up rich food, I want you to give up sex.” The man is shocked and mumbles: “OK. Will I live longer?” The doctor replies: “No, but it’ll certainly seem that way.”

As he delivers the punchline, the 77-year-old Hockney howls like he’s heard it for the first time: a throaty roar that culminates in a hard-earned smoker’s wheeze. We are sitting in a pair of paint-spattered armchairs in the studio annexe of his house high in the Hollywood Hills. He spends most of his days in here. It has everything he needs, not least a few gallons of mineral water and a stash of 2,000 Camel Wides cigarettes, just in case Los Angeles is hit by an earthquake.

Arriving at the house, zipping up the twisty roads from Sunset Boulevard, dodging garbage trucks bombing down the other way, it is impossible not to be overcome by deja vu. Long before Google Earth, Hockney depicted these hills in absurd oranges, greens, blues and reds in landscapes such as Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio, 1980. Now I’m here, what I had taken for a hyper-real acrylic fantasy turns out to be disconcertingly realistic, another example of Hockney’s gift for capturing some essence of wherever or whomever he paints.

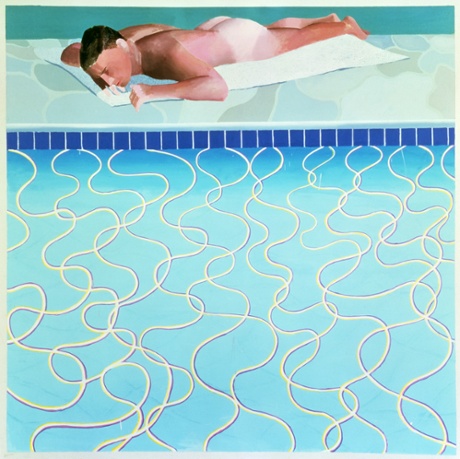

The house, which Hockney bought in the late 1970s, is tucked behind utilitarian grey gates that give little hint of the wonderland beyond them. Once inside, the land drops into a jungle of exotic ferns and palms down to the famous swimming pool at the bottom. A harsh sun flickers off iridescent cerulean and pink paint. Artist Howard Hodgkin once said the house was “as romantic and artificial as I had hoped” and it is. But today all is peaceful and a smattering of leaves on the pool’s surface hints at sporadic use. It might have been a while since wild parties raged into the night or naked bodies hauled themselves on to the hot stones at the water’s edge.

“I don’t go out, I hardly ever leave here,” admits Hockney, as we take our seats in the studio. He is dressed as plainly as his forbidding gates – dark grey cardigan, slate-grey pinstripe trousers and, incongruously, considering his disdain for all exercise, Skechers running shoes – again in contrast to the vibrant work that surrounds him. “I go out to the dentist, the doctor, the bookstore and the marijuana store, because you have to go to each of those yourself. And that’s it. I never go out because I’m much too deaf really. I can hear you now, but if there were two people speaking quite quietly, I wouldn’t be able to, because I hear everything in one noise. So I don’t really have a social life much, because a social life is talking and listening and I can’t really listen. But it’s fine, I’ve lots to do, I’m OK.”

Is Hockney a regular customer at the marijuana store? “Well, it’s…” he starts, reaching into his back pocket for his wallet, before presenting his “medical marijuana patient verification” card like it’s a police check. “To get this you have to say, ‘Well, bad back, anxiety or something’ and you just get it. And it’s very nice actually. I don’t smoke much, but sometimes of an evening, because I don’t have alcohol any more, a bit of marijuana’s nice.”

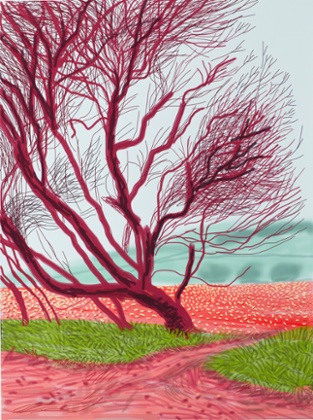

Hockney returned to Los Angeles in the summer of 2013, after eight years living in England, mostly in Bridlington, east Yorkshire. It had been a productive period that saw him extend himself both technically and technologically. His output was astonishing for an artist of any age: from thousands of tiny doodles on his iPhone and then iPad to behemoth landscapes of the Wolds, notably the 40ft by 15ft Bigger Trees Near Warter, which culminated in a triumphant survey at the Royal Academy in 2012. More than 600,000 people saw David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, double the projected figure; a similar number visited when the show transferred to Bilbao and Cologne.

But Hockney’s departure from Yorkshire was sudden, even unsatisfactory. It didn’t feel like we got to say goodbye. There were extenuating and personal factors. In September 2012, Hockney had a stroke: he didn’t realise at first, he’d got up early and went out to buy the newspaper, but he found himself unable to finish his sentences. Then in March last year, one of his studio assistants, 23-year-old Dominic Elliott, died in his house in Bridlington after drinking household drain cleaner while high on ecstasy and cocaine. Hockney’s deafness, which is hereditary and requires him to wear hearing aids in both ears, worsened.

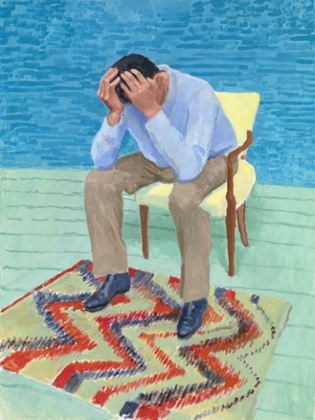

Returning to the Hollywood Hills, his home for much of the 1980s and 1990s, has been cathartic, Hockney believes now. He had been working on sombre landscapes in Yorkshire drawn in charcoal before he left, but back in California, he decided he wanted to use bold acrylic paints again and make some portraits. The first was of Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, his lead studio assistant, sitting on a chair with his head buried in his hands.

“I just started that painting of JP,” says Hockney. “We were very down, very down. We were down because of what had happened in England and we had just come back here. Things were going on then, but I started these portraits and that was it. I just painted 50 people, they are all in the same chair, the same position. They took three days each really, about three six-hour sessions, and I enjoyed them. I had people come and sit there and I said, ‘It’s an 18-hour exposure, not the fifth-of-a-second one.’”

Since then, Hockney hasn’t stopped and he continues to tinker with technology to produce new work. (“I work eight days a week,” sighs Gonçalves de Lima, with faux exasperation. “Every day is Monday.”) He recently completed a set of five photographic “drawings”: perspective-tweaked montages of people arranged around his studio that are displayed on high-definition screens. These are on display at Pace Gallery in New York until 10 January, along with some of the chair portraits he made when he first returned to Los Angeles and group paintings of dancers that are his homage to Henri Matisse’s Dance.

When we meet, Hockney has also just begun a series of more conventional studies of card players. His blue eyes sparkling, he says that he now understands what drew Cezanne and Caravaggio to the same subject. “They sit reasonably still,” he explains, “you’ve got their hands on the table, they are concentrating, they are ignoring me, yet I feel I’m close to them.”

While Hockney is determinedly looking forward, for the rest of us there is a satisfying opportunity for retrospection with a new feature-length BFI/BBC documentary about his life and work. Directed by Randall Wright, who also made Lucian Freud: Painted Life, it features a trove of personal photographs and home movies, never before seen. Hockney supplies an idiosyncratic commentary, expounding his forthright views on everything from the state of modern art to why crinkled chips are preferable, because there’s more surface area. Friends describe an obsessive creator, not always easy to live with, who puts art before everything.

In his studio, Hockney fires up a Camel Wide – only 1,999 left now – and steels himself for questions from fellow artists, old friends and Observer readers. He may be near-deaf, he’s getting on, but he remains in boisterous, cantankerous and irrepressible spirit.

Hockney is on general release from 28 Nov and on BBC2 next year. A special preview screening in cinemas on 25 Nov will be followed by a live Q&A with David Hockney from his LA studio. Hockney is a BFI/BBC film in association with Screen Yorkshire, British Film Company and the Smithsonian Channel.

YOU ASK THE QUESTIONS

If you were hosting a fantasy dinner party for five guests, who would be on your guest list? They can be dead or alive.

Victoria Frith, Newcastle

Five people: Picasso, Goya, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, and a writer, perhaps I’ll say Goethe, because I know he was an interesting conversationalist and I don’t know much about him.

I often make a pilgrimage to your work at Salts Mill in Saltaire and am touched by the painting of your mother’s last moments. When you make a piece of work that is deeply personal like this, how do you feel when you return to look at it, say a few months or years later?

Rebecca Carr, Bradley, North Yorkshire

Well, I think about her. I often think about my mother. During her last 10 years I went four times a year. She lived to be 99. I’d stay in Bridlington for about a week and I’d always draw her, always. I’d say that it might be the last time I see her, I don’t know. And I still have them all, I kept them all. That painting, I own it, it’s just lent to Saltaire. I’ve kept all the pictures of my family the only one I let go was to the Tate, because they wanted it, but I do keep lots and then I’m going to give them away to museums and so on.

One of the things that I’ve always loved about you and your work is that you seem to be totally oblivious to criticism. Is that impression true? Or has any criticism ever hurt you or forced you to reconsider your work?

utrechtnik, posted online

No, it hasn’t. Most criticism is not much at all. If you took notice of critics, you’d be mad. I never cared about Brian Sewell, he always attacks me, he attacks every contemporary English artist, but he’s just a joke really. I never took him seriously. Yeah, I’ve always been able to just ignore it. I’ve always had a lot of confidence actually. When I got to the Royal College of Art, people used to mock me: “Trouble at t’mill, Mr Ormondroyd”, stuff like that. I didn’t take any notice, but sometimes I’d look at their drawings and think: “If I drew like that, I’d keep my mouth shut.” But I never cared, it didn’t matter. When I was first in London, I just assumed that everybody would be really good in London, but within being two weeks at the Royal College, I’d sized up a lot of things. I could see, “Well, they’re not that good.”

I always had confidence, because I could draw. I was aware I had a talent; I knew that from an early age. I used to think: “Well, if times are bad, I could always draw portraits in the Coupole, in Paris.” There used to be a little man who drew portraits and I’d think: “I could do that as well.” It gives you a confidence if you think you can always do this or do that.

You always have been a passionate man: now that you’re older, what is the role of love in your life? Has it changed?

tri2002, posted online

I love my work. And I think the work has love, actually. I’m living alone now. Well, I live with JP, but we’re not lovers. I’m certainly open to romantic love! I’m always open to it! But I’m not expecting it now. I’ve had enough, I’m reasonably happy here. I’m not unhappy. I’m working, that’s all I want to do, and there is love in my life. I love life. I write it at the end of letters – “Love life, David Hockney”. When I’m working, I feel like Picasso, I feel I’m 30. When I stop I know I’m not, but when I paint, I stand up for six hours a day and yeah, I feel I’m 30. Picasso said that, from the age of 30 to 90, he always felt 30 when he painted.

What do you say to those non-smokers who are particularly sanctimonious about your habit?

georges1, posted online

One time, I was walking in Holland Park (I was sitting for Lucian Freud), and I stopped to watch some black rabbits playing. So I sat on a seat watching and then some magpies came down, black and white birds, and they looked rather good. I was sitting there having a cigarette and three girls come running by, jogging and see me and come: “Ow, ow… ” [wags finger]. And I sat there and thought: “They think they are very healthy, but they haven’t seen the rabbits.” And I thought: “Well, I’m healthier than they are.”

People are mean-spirited, yes they are. They are mean-spirited and dreary. Dreary! I use the word dreary, because I think lots of people are dreary and I don’t care about them actually. They are dreary. Too dreary.

Do you think that through your art, you have changed people’s attitudes to homosexuality and, if so, how important is that to you?

WolfHome, posted online

Probably, which is a good thing, I think. Yeah, I knew when I was very young that gay people hid things and I didn’t want to do that. I thought: “Well, I’m just going to be an artist, I have to be honest.” You have to be honest. So that was it, I just was gay and it didn’t worry me. And I always used to say that we lived in bohemia and bohemia is a tolerant place. There was a bohemia then. There isn’t now, because you need cheap places for bohemia, don’t you? Paris was once a bohemian city, it isn’t now, too rich. New York is becoming like that. I don’t think there’s much of bohemia in New York now.

You have a fondness for east Yorkshire and as I’ve lived here all my life too, I wonder do you prefer Filey or Bridlington fish and chips? Personally it’s Wetwang.

Chris Whitlock, Beverley

Oh, I know the shop in Wetwang. We often had lunch there, the Wetwang fish and chip shop. It’s very, very good. If we were out near there painting or something, we’d go have lunch, always delicious. Very big pieces of fish, but they are always cooked just for you and the batter is crisp and marvellous, soft haddock. Delicious! You have to eat them when they are cooked, fish and chips, you do, even taking them home is not so good. They lose their crispness. We had fish and chips a lot: JP used to go and he’d make sure the fish was kept separate from the chips, he’d ask for that. Ha ha! And then they were better, because the chips would make it a bit soggy on the way back.

Who makes you laugh the most?

Una Barras-Hargan, Kuwait

Well, we always like to have a good laugh at least once a day and there’s plenty to laugh about. But I think people are losing their humour a bit in England and America. When people sit for me, I’m not talking to them much. And if they talk to me, I can’t really hear it, so we are not having conversations. This is the deafness again. I don’t hear it.

If you could have any one painting from history hanging in your bedroom, which one would it be? And if in 2,000 years’ time only a handful of your paintings were still to exist, which one would you most like to last?

spum, posted online

There’s a drawing by Rembrandt, I think it’s the greatest drawing ever done. It’s in the British Museum and it’s of a family teaching a child to walk, so it’s a universal thing, everybody has experienced this or seen it happen. Everybody. I used to print out Rembrandt drawings big and give them to people and say: “If you find a better drawing send it to me. But if you find a better one it will be by Goya or Michelangelo perhaps.” But I don’t think there is one actually. It’s a magnificent drawing, magnificent.

For mine, 2,000 years! That’s a very long time, I don’t think they’ll be much by then. But I do paint my pictures to last actually and they are painted correctly, meaning they are painted fat on thin [allowing lower layers to dry to avoid cracks on the surface], the paint stands up. The first thing I did when I got money was buy better canvas and better-quality paint, because I knew you needed it and I can look at those pictures from 50 years ago and they are still OK. If I had to pick one, I’d say the portrait of my parents. But I don’t know whether it would last 2,000 years. They might, but they only last if somebody really wants to see it; if they are put away in storage, they will crumble.

Who was the most beautiful person you ever kissed?

Peter, Exmoor

Peter Schlesinger perhaps. I met him when he was 18, I was 28. He was a very, very, very sexy boy and he was a bright boy as well. I’d met sexy boys before, but they weren’t very bright. He was bright, a different kind of person.

There have been some critical articles about your belief that artists in the past used camera obscura and camera lucida. How do you react to the slightly snobby disdain for technology being used in art?

abominablevole, posted online

The book I did, Secret Knowledge, can’t be dismissed. I know it can’t be dismissed. And actually it’s gaining more and more now, more people believe it, understand that perspective itself comes from optics. It does. It can’t come from anywhere else, if you really think about it. The Chinese didn’t have a glass industry, so they never developed optics, so the Chinese never had a vanishing point. Art history has been a bit mad on that subject. Art history isn’t that old, it’s only 150 years old really, and they missed things. But we are going to correct it. Nobody can actually say it is not true at all, I know they can’t. I know I’m right.

If someone compliments you on having written The History Boys, are you tempted to murmur “How very kind” and move on?

Georges, Brighton

Ha ha, yes. Well, I’ve never been confused with him, but Alan Bennett told me once that he’d signed my name after someone told him: “We loved your opera work.”

ARTISTS ASK THE QUESTIONS

I have a sense that as I get older, I want to make happier and happier art – what do you think, David?

Grayson Perry, artist

Good question, yes. Well, it’s playful, there’s a lot of playfulness. I don’t know whether it’s happy, but I don’t think it’s unhappy. The mood you are in always comes out in your work. Actually, if I’m very down and unhappy, I don’t work at all. That’s not that often. Mostly, I work seven days a week, that’s all I do now. I’m what, 77, and I feel I’m just still exploring things and I’m exploring perspective in some new way at the moment. Well, that’s interesting for me.

I’m not a miserable artist! No, I’m not. Art should be about joy. I haven’t seen the Matisse exhibition [the Tate’s Cut-Outs show which has moved to the US] yet, I shall go next week when I’m in New York, but I’m looking forward to it. It’s just pure joy that, Matisse. Young and old love it, don’t they? And I think for my show at the Royal Academy they had young and old, so that must be something.

Do you think we should allow fracking in our country?

Cornelia Parker, sculptor

I suppose you’ve got to say yes, because you can’t stop it really. They needed coal, they needed oil, we can go on and on about oil, but if there wasn’t any, what would happen? On the Wolds they are beginning to build wind turbines. I know one place where for 200 years there were these trees, I painted them and then one day they were all chopped down. I was horrified. But then I thought: “Well, I have a pencil, and pencils are made of wood, so somebody has to chop them down.” Ruskin said: “Why build bridges between Manchester and Liverpool just to get the businessman there quicker?” A hundred years later they want to keep the bridges and things. It’s always like that, isn’t it really?

How would you describe the place where the things you’ve read and the music you know enters the pictures you make? I look at your landscapes and somehow they look to me like… Beethoven. Is a form of synesthesia at work?

Ali Smith, author

I don’t know about synesthesia. Someone said I was a synesthesiast, because of the colour I used in the stage designs I did for opera years ago, but I don’t think so really. But Beethoven, I might have been listening to Beethoven sometimes when I did a landscape. I remember in the car driving on Woldgate, I would play Glenn Gould’s version of Franz Liszt’s version of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony on the piano. The car was the last place I could listen to music really, because it was a good car, it had 18 speakers.

How did you come up with such a good way of dressing? Was it deliberately thought-out or a chance experiment that worked well?

Bella Freud, fashion designer

It was chance experiment! I don’t know, my father was a dandy. He always wore suits and they were always made for him. He didn’t earn much money, but in those days, people had suits made. He just had them made in Bradford. Now, I have about 10 suits and that’s all I wear really. Fallan & Harvey in Savile Row made them for maybe 20 years or something. And I paint in them, there’s ones that are messier than others. But that’s all I wear.

When you are a young artist, you want to attract attention. You need to, but once you’d attracted attention that was it. I don’t really think about it much, I just put on something. Today I put these newer trousers on. Well, they are newer than the old ones.

Do you have the same passion for making artwork that you had when you were younger?

David Shrigley, artist

Even more. I’m working more now than I did 20 years ago, producing more. Probably because I’m surer of things. I’m quite confident about what I’m doing. I know it’s interesting. I know because I see other people’s work and I know, mine is different. I know I’m on my own really a bit. I like [your] work, I saw [your] show at the Hayward. Very, very good, I thought. A memorable show.

Do you still draw in the more traditional way, in the way you first did when you left the Royal College?

Paul Smith, fashion designer

Yeah, I draw, I do. In 2013, I did about 30 portraits, charcoal drawings, quite conventional really, but not that conventional. They took two days to draw. From the age of 16 to the age of 20, all I did was really draw, because I was at the art school in Bradford and in Bradford you could be in the school from nine in the morning to nine at night, because as a full-time student, you could go in the evenings and you’d have a life class then. So I drew for four years. Well, you get better if you do this, anybody would, but not many people even try it now, that’s the problem. I did and I got better quickly.

I don’t know what art schools are like now, but I’m told they don’t do drawing. That seems a bit mad to me that. Drawing is going to be needed in the future. Video games and things, that’s people drawing. It’s always back to the drawing board. Always. Even on the computer, it’s back to the drawing board.

When are we going to see you? When can we take you out for dinner?

Sir Peter Blake, artist

I don’t know, but I’ve no plans to go back [to the UK] yet. I’m a bit reluctant to travel really. First of all, it’s a bit difficult travelling alone, because you have to hear things. And I’m working here, I’ve no reason to go to England at the moment. It’s probably over now, Bridlington. It was a very, very good inspiration, I didn’t plan to go to Bridlington, I just went there in about 2004 and I began doing watercolours and things. Peter’s nice, he’s an old friend, but I’m just going to stay here. Why give up work here?

How is drawing different using the iPad? Does drawing with the iPad give you the same feeling as drawing on paper?

Yinka Shonibare, artist

Well, no it doesn’t, because you are drawing on a sheet of glass. But on an iPad you can draw for ever and you can’t on a sheet of paper. And on an iPad you draw a bit differently, but that’s all you do. Drawing is 50,000 years old, isn’t it? I think it comes from very deep within us actually. When all those people in the 1970s were trying to give up drawing, I did go and see them and they said: “Oh, you don’t need to draw now.” And I did point out: “Well, why don’t you tell that to that little child there? Tell them you don’t need to draw and see what happens.” Young people draw, they start making marks, everybody does.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.