We all know that rising sea levels will devastate low-lying islands and coastal cities, but it can be hard to visualise what that looks like at an individual level. Boris Maas demonstrates this clearly with a chair whose legs have been raised to keep us above the 65 centimetres predicted rise in sea levels by 2100. If we could sit atop it, it would feel vertiginous as the chair towers above us.

Opposite this work, and opposite in outcome, is an imagined picture of the Earth if all the oceans and seas dried up and this terraformed planet looked more like Mars than the blue marble we inhabit.

These two works are part of an exhibition titled ‘A World of Water’, which examines our relationship with the water that covers most of the Earth’s surface. The exhibition is at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich as part of the ‘Can the seas survive us?’ season.

Visitors will inevitably see this exhibition through the lens of climate change, and while that is referenced in the show, it also takes us further back through history. Historical maps are on display, including some of the earliest of the Anglian coast and many showing how close this part of the UK is to the Netherlands, which ties into several Dutch artists’ inclusion in the show.

The Anglo-Dutch relationship also extends to a salon hang of historical paintings by Dutch and British painters, including a work by Hendrick van Anthonissen that revealed a beached whale when it was carefully restored a decade ago. In truth, I’ve never given much thought to this link across the sea to the Netherlands, but given how close they are, it makes sense.

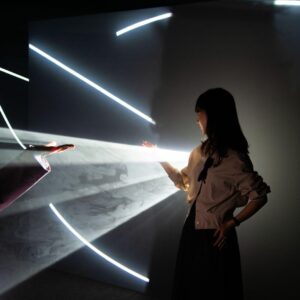

The show includes big names, like Maggi Hambling and Olafur Eliasson, but lesser-known artists mostly overshadow them. The exception is Eva Rothchild’s hard-to-miss red-and-white seawall, which cuts across the largest gallery. Detritus is piled up against it, just as human architectural interventions act as accumulation points for natural and man-made items.

I was drawn to Claire Cansick’s vast seascapes, which make you feel like the waves could roll right over you. They feel like they could be from any era until you spot the wind turbines on the horizon – proving that even the open water can’t avoid humanity’s footprint. Julian Charriere also looks into human expansion into the deep oceans as his images of what’s termed ‘the midnight zone’, an area being considered for deep sea mining, are teeming with life despite the name suggesting otherwise.

It’s a show that asks questions about our relationship with the ocean and encourages discussion rather than providing answers. This is aligned with the gallery’s multi-year programming intent of fostering discussion on broad topics that impact us all.

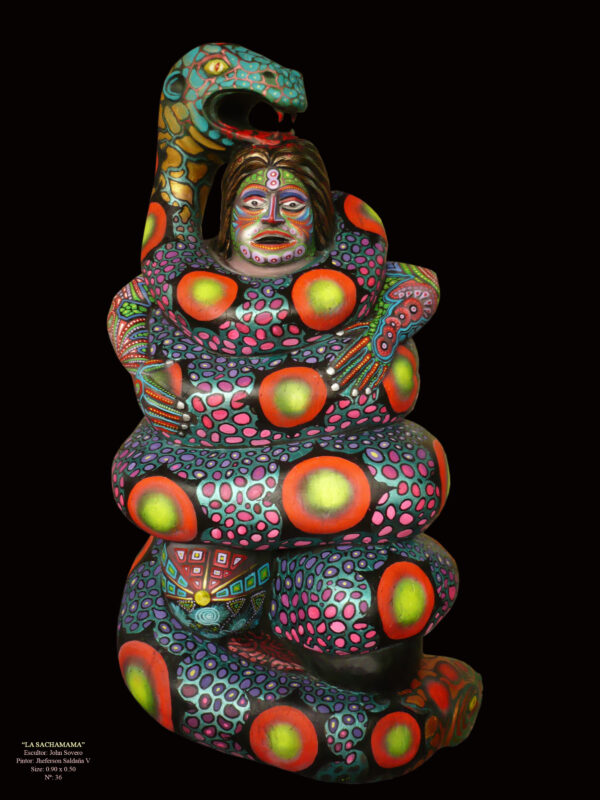

‘A World of Water’ runs concurrently with Yuki Kihara’s Darwin in Paradise Camp exhibition. It’s a fun show with a tropical open hut in the centre, films with drag actors, biological specimens, and a painting by Paul Gauguin. The exhibition redresses Western views of the Pacific Islands by examining how Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings may have been inspired by Samoa’s landscapes and how Charles Darwin changed his research on specific species to fit into the heteronormative view of the world that existed in Victorian times.

It feels completely separate from the other more extensive exhibition, but they work well together. Yuki Kihara’s works and their tighter focus complement the broader ‘A World of Water’.

Together, the two exhibitions ask important questions about our relationship with the seas and ask us to form our own views on whether the seas can survive us. I’m still unsure whether I think they can, but it’s great to consider this in these two sea-worthy exhibitions.

A World of Water and Darwin in Paradise Camp: Yuki Kihara run until 3rd August. Entrance to the museum is on a pay-if-and-what-you-can basis. It’s part of ‘Can the Seas Survive Us?’ season, which runs until 26th October at The Sainsbury Centre in Norwich.