Two minutes into my interview with Seffa Klien, granddaughter of Yves Klein, we are already discussing the dreams we had the night before—fitting for a conversation focused on the idea of an inner sky or “Un Ciel Intérieur”, the inaugural group show at the Musée d’Art et de Culture Soufis MTO in Paris. The show takes the concept of an interior sky from the writings of Henry Corbin, a scholar of Sufism. The idea? To find the divine essence in every experience. For an artist with an incredibly physical practice, Klein is also acutely tapped into her own inner landscape. Below, we talk about her practice, cosmic consciousness, and how everything is a technology.

The show is all about this idea of an inner life and inner sky. How do you see this? How does the title “An Interior Sky” relate to your work?

I mean, I think it’s a really perfect title. I always imagine that I have this kind of landscape within and, yeah, the sky represents what I’m basically for me, what I put my attention on, which is, you know, looking up towards the highest states that I’ve been able to experience, the kind of channels of energy that I feel like open the most doors for me, for my consciousness, as well as just like a sense of of focus and centeredness that grounds me. The sky grounds me.

How do you feel your work dialogues with Sufisim?

I feel like people would have known the element of infinity before math could have shown up to describe it. You know what I mean? I feel like there are these elements of reality that people, whether it’s through science and math or through dreams and meditation, can access this information and that’s why I think there’s such continuity. This idea of, like the 100th monkey, and these things that reappear throughout human history, seemingly without physical influence, I think it has to do with this idea of cosmic consciousness—everything being information that we can access. That’s really what the pieces are about: this idea of agency to be able to access everything in the universe, which is also, I believe, quite tied to Sufism and the idea of divinity being within, being accessible through the heart.

What role do your dreams and visions have in your practice?

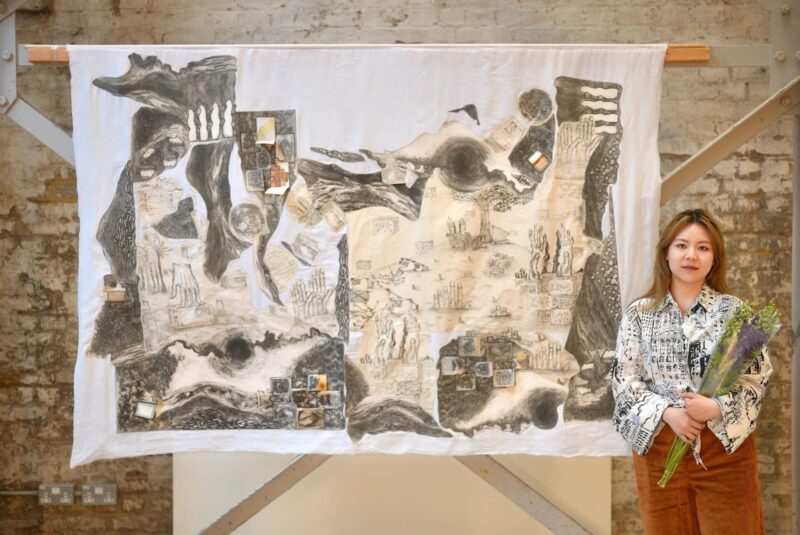

A lot of my work comes from dreams. So the works that are in the lower room are part of a series called Multiple Displacement Theory, which came from a dream. A name like that could only come from a dream. Honestly, it’s such a strange string of words it could have only come out of a dream. The way I make art is very rooted in my intuition and my dreams, and I like asking questions and receiving answers and interpreting my dreams. I have dreams and visions, both of which I use.

How do you distinguish between the two?

Dreams are when I’m really sleeping, and visions are when I’m like, partially awake, you know, or just falling asleep. That’s kind of the difference. They have different energies. Multiple Displacement Theory came from a dream and it was about how we travel through space and how our consciousness can travel through space using geometries. This dream was the beginning of this sort of technology that revealed itself to me. It has continued to reveal itself to me. If you think about everything, everything is technology: consciousness, language, spirtituality—these things are also technologies. So this way of thinking of a technology has started revealing itself to me around 2017 after this dream. Making the work has been a way of meditating on that intelligence and getting more information from it.

What is your definition of technology and your idea of spirituality as technology?

Technology is all of the things that we’ve developed to create society and allow us to transcend. I think one of the oldest technologies are spirituality and written language and those have really informed human consciousness. Technology is also the manipulation of space, time, ideas and matter to create a new way of being.

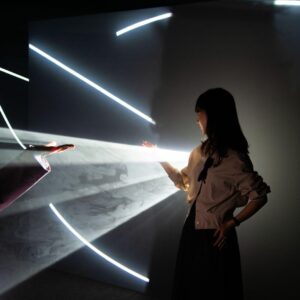

I love that Sufism emphasizes how spirituality is accessible to everybody. I think spirituality also changes and evolves over time throughout thousands of years of human history. I’m asking myself what it means to be pursuing spirituality today, in the information age. Everything is information and that’s what the pieces on the first floor are about, this idea of the equality of space and time and our place in that picture, where the circle is representing the infinite and the square is representing the finite. It’s seeing the way in which the two work together to kind of create these moments, these experiences of revelation and discovery. That’s a beautiful part of being alive, you know?

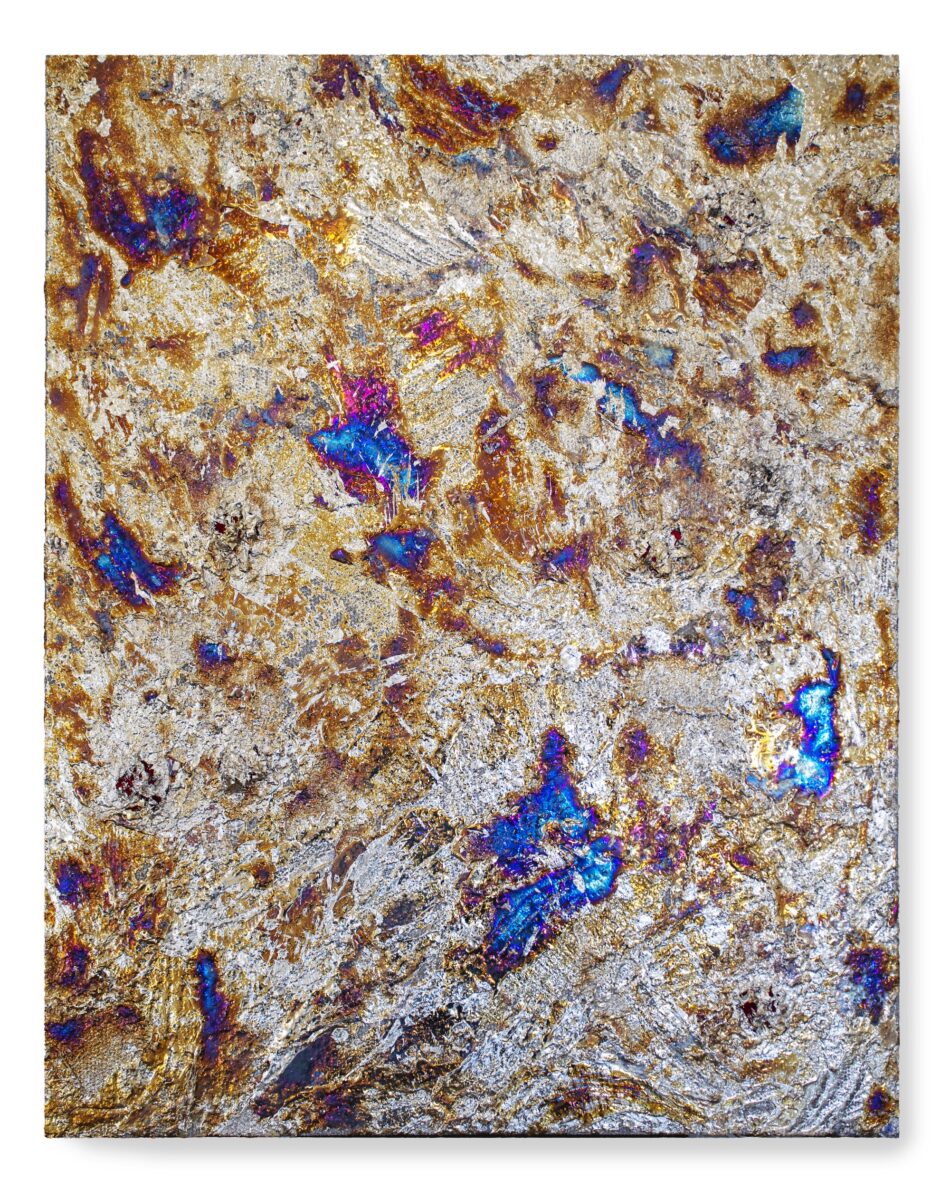

I always knew that the spiritual world was what I liked and where I needed my focus, since I was a teenager. Something that’s also really important to me, is engaging with the scientific, mathematical world and understanding nature that way, too. This is echoed in the fact that the work is made of this metal called Bismuth.

I was going to ask about Bismuth! It’s a material you’ve worked with for a while now and it’s a metal that has really unique properties, right?

Bismuth’s physical properties lend themselves to my ideas. By physical, I mean subatomic. Some of those properties include its ability to melt at a lower temperature, at a temperature that’s safe for me. It’s not as hot as, for example, silver. It doesn’t need a foundry. There’s a danger, but it’s very accessible to me and to my body. It also has this element of transformation, where all the colors and the piece are created through an oxidation process. I also love this kind of infinite expression within it. When I apply the metal, it’s silver and then all the colors that you’re seeing in the pieces have been brought out through the process of oxidation. So there’s a spectrum of colors kind of hidden in the intelligence of the metal itself. I think that’s such a beautiful metaphor for everything in life—there’s kind of like this infinite spectrum and everything that can be brought out.

When did you first start working with Bismuth and how did you come across it?

I came across it in 2017 and I had been working with this other metal called Gallium, which I came across from random research on YouTube. I also have researched a lot. I grew up in Sedona. I’ve been around a lot of minerals and crystals and those types of things. I’ve researched a lot of Astronomy and Astrophysics. I’m just very familiar with the periodic table. I’m really interested in where things are formed in the universe. I really understand the foundational elements of stars and different types of stars and how different types of elements and events are really unique—some of the highest energy events in the universe are very heavy. Bismuth has this hidden mystery element and it looks like it has that intelligence—like space energy.

There are seven artists in the show. Do you feel a particular connection to another artist’s work?

I really like that they specifically wanted all of our works to dialog. There’s this piece there that has these geometries mixed with flower drawings and it resonates so much with me, because I’ve also really studied the flowers a lot and tried to study them in terms of their geometric essence, as well as the energy held by them. So I loved that piece. I felt really aligned with that. That connects to pieces which have flowers in them encased by metal. On the upper floor, my work was curated next to Bianca Bondi’s. I think it was part of this idea of transformation. I’m not sure exactly what her process is, but she also uses oxidation. I definitely felt a kinship there with her work.

Nature is central to the new museum with the garden being a space for contemplative thought. How has your connection to nature informed your work and what is your relationship with nature?

I grew up on a farm and from a young age felt very close to nature. I was definitely influenced by the energy of being in a place that’s so beautiful, the energy of the desert, which is such a spiritual, quiet, intelligent landscape. I’ve just always been very, very close to nature. It’s super important to me. It’s kind of how I ground myself the best, especially through trees—trees and really heavy works of art. I’ve always been really interested in the idea of symbiosis with nature and investigating what it means to be human and how we can kind of imagine new states of being and fast forwarding human consciousness, as we’re interwoven with nature.

What do you want to communicate with your work?

I think it’s really just that sense of openness that I want to communicate, which can be felt by anybody at any age. A sense of access and openness—it’s a kind of inspiration, this little spark of, oh, there’s something to discover. So it’s that spark of inspiration tinged with desire and wonder. Something that is reminding you of a time when you felt connected to something larger. It’s experienced as something different by every person and it depends on their own spirituality, their internal landscape. It’s interesting to hear different people’s experiences with the work.

My goal from the beginning was to create an experience that can be shared by somebody who is, you know, quite versed in art history and quite developed spiritually, as well as, like a child, or, you know, an atheist, or somebody who’s just never heard of any of this. I feel like wisdom is something that does not require any qualifications other than openness.

Your artistic practice is quite physical, yet dreams and visions also play a central role in your creative process. Do you have to be in this altered state when you’re executing a piece or is it more grounded?

I’m working with hot metal, so I’m very focused. I actually love the physicality of the process of metal. When I’m coming up with the ideas, when I’m sketching and working that flow, I’m in this very soft state and I’m using gouache or graphite and it’s soft and immediate. When I’m making these multi metal pieces, I’m wearing a gas mask and there’s fire and it’s hot and it’s really heavy and it’s physically difficult. The physicality of that really grounds me in my body. I’ve always really valued hard work, and I grew up on a farm, and like the kind of feeling of doing physical labor, the way it feels in the body. There’s something quite profound about plugging these very esoteric, immaterial things into something that’s very physical and material and heavy. It’s funny, all my work is heavy. Even before I used this metal, I used to use plaster and those pieces are really heavy, too…It’s like I’m longing to ground these things.

My home is in the sky, my interior sky, that’s my home. My home is also these ideas and the home I live in, there’s an idea of sinking into the physicality of that. It’s like, well, I’m in this physical world and I need to ground myself. So, it’s this act of bridging. It’s that dichotomy. You can’t have one without the other, right?