If you didn’t already have FOMO for Berlin in the 1990s, then visiting Dream On — Berlin, the 90s, the retrospective at CO Berlin showcasing a textbook archive by East German photography agency OSTKREUZ of this unique transitional stage for the “reunified” German capital, should certainly change that.

The exhibition opens with short biographies of founding OSTKREUZ members; East German photographers who formed a collective following the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1990 modelled after the Magnum Agency.

One of the first images the viewer encounters is of five young people on route, seen from behind. Holding hands and carrying suitcases, they converge with a crowd of revellers seemingly headed in the opposite direction. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, millions of people – nearly 4 percent of the population of East Germany – migrated West over the ensuing two decades whilst about half as many spilt into the now nearly vacant half of Berlin.

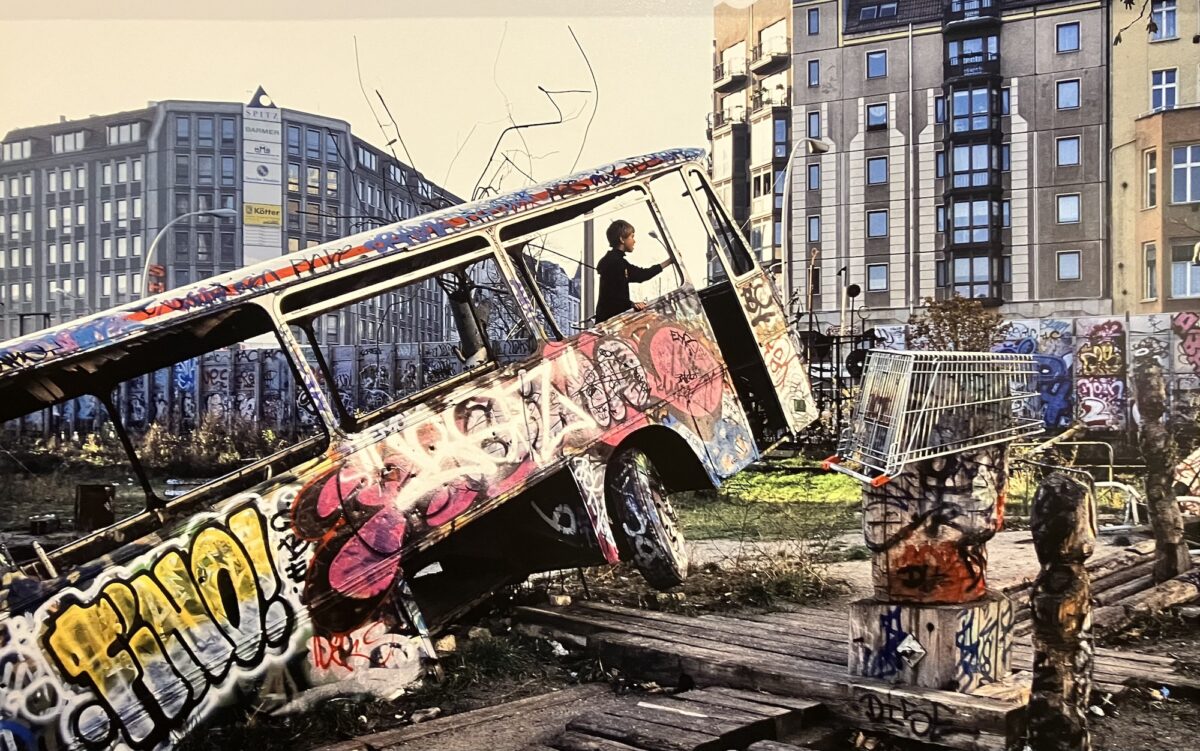

Ripe for the plucking, East Berlin had a surplus of emptiness. From vacant lots and abandoned homes, to disused infrastructure and the green area around the former Wall itself, the process of developing this largely unclaimed swath of urban territory would take years if not decades. In the meantime, the accessibility of space meant unprecedented potential for what the exhibition describes as “temporary initiatives” and countercultural trial and error.

Many have compared Berlin in the ‘90s to New York in the ‘70s: a heyday when the city was a burgeoning playground for art, night life, and un-categorisable experimentation. Both of the cities’ creative legacies were shaped during these “utopian” eras by empty spaces, subsequent squat movements, and activist street art, but what NYC never had was an unparalleled state of flux brought on by nationalistic restructuring; where a city that once existed virtually ceased to be, and the memory of a discontinued nation lived on in the cultural imagination as physical remnants fought for the right to endure.

This is seen in the first room of the exhibition in images of grocery store workers sorting inventory, either readying to close completely or making space on shelves for the influx of Western brands. One image depicts three slightly bewildered looking employees standing in an aisle of Spee — one of the few quirky East German brands that not only survived the transition from Communism, but weathered competition and went on to thrive in modern Germany, becoming the country’s third most popular laundry detergent.

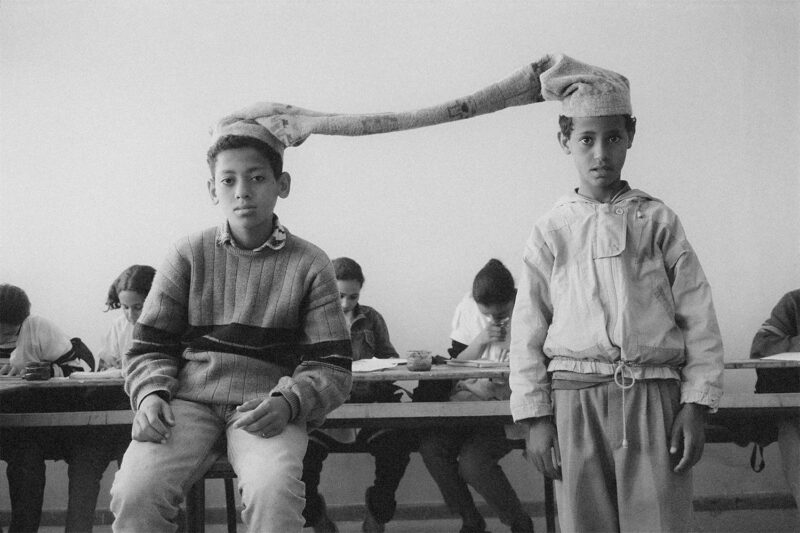

The sober observation of such elemental but ubiquitous tokens of daily life embodies an understated eye that is pervasive throughout the exhibition; the photographer is present, yet emotionally detached. Accompanying texts are informative, yet distant — not elaborating into personal narratives but also not neglecting to provide a basic level of context, almost as if to be intentionally broad.

The style is eloquently utilitarian and lends itself to a characteristically GDR photographic aesthetic — one that OSTKREUZ cofounder Ute Mahler has described as “reserved, quiet, and intense with a touch of melancholy.”

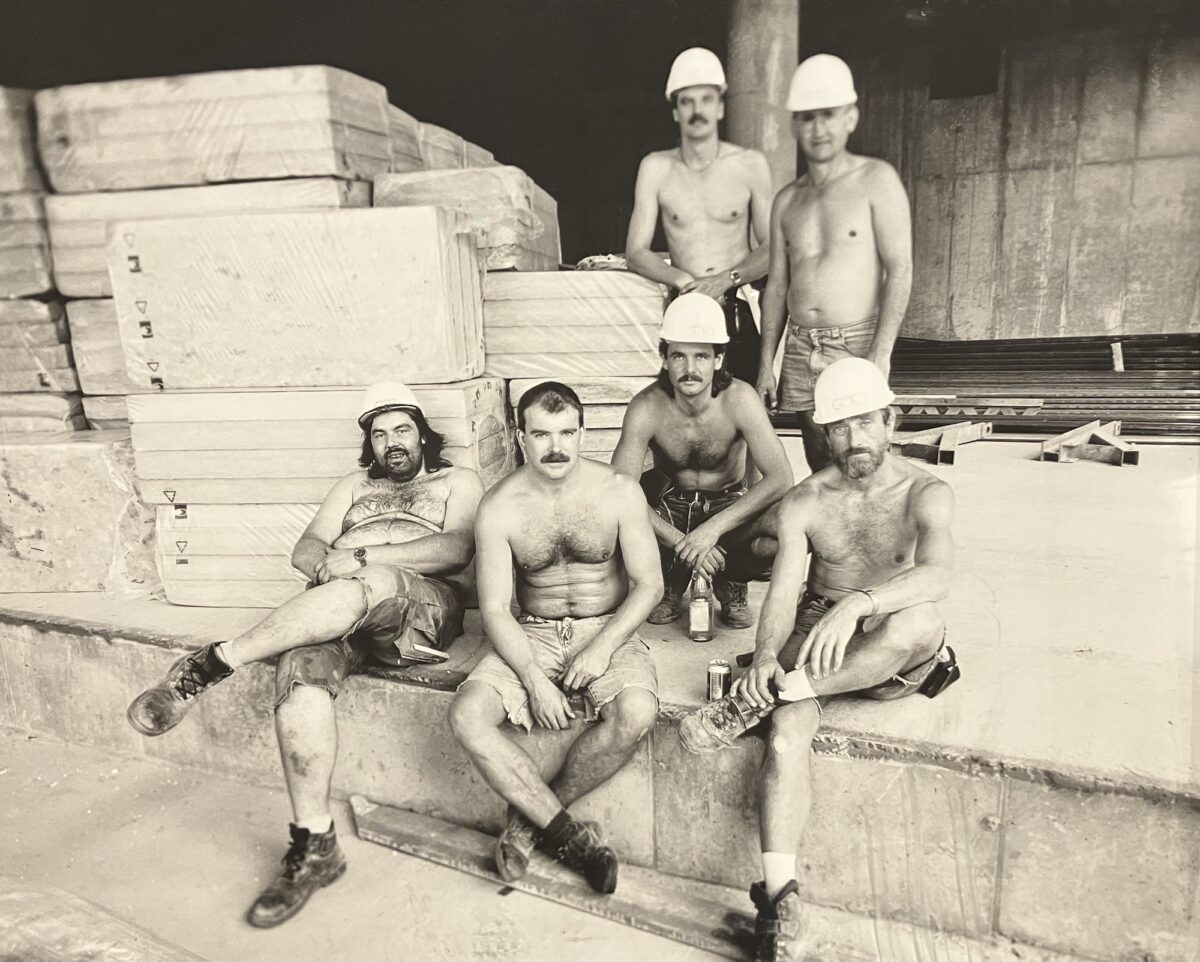

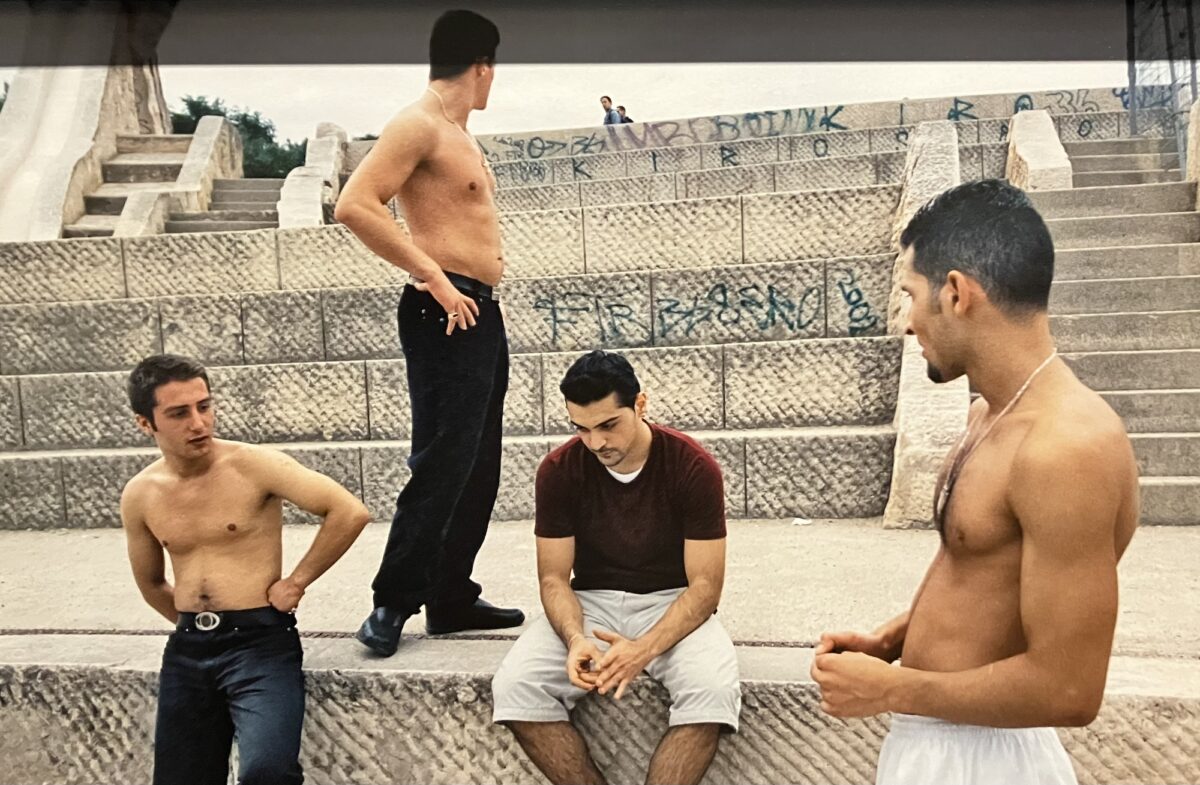

Another GDR photographic tradition prevalent in the collection is the custom of taking portraits of workers. From shop staff to construction crews at the site of the ever-evolving Potsdamer Platz — which symbolised the city’s new centre and hybrid zone that blurred the boundaries between municipal and privately owned space — these group photos of work teams convey a humanised documentation of the labour force.

Berliners and visitors familiar with the city will delight in rarely seen iterations of public transit; growing pains in the form of discontinued trains from a city whose map expanded overnight. White and cherry red carriages look foreign compared to the contemporary mustard-maroon colour scheme, and tear across a cityscape that, compared to today, looks veritably naked.

Art buffs will recognise Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Reichstag from 1995. But while the canon has sufficiently disseminated images of the legislative building encased in 100,000 square metres of polypropylene fabric, what fewer people might have seen is the images of the two-week long open air party that took place on the lawn adjacent. Talk about FOMO!

Despite the potential for hitting at heartstrings, the exhibition keeps it pretty topical. There’s a lot of potential for emotional triggering with this topic; from the more modern dissipation of Berlin’s free space to the dissolution of a country that no longer exists. But that’s not the objective of OSTKREUZ, whose incentive is to convey an accurate and humanistic outlook of events as they occurred.

Nowadays, a lot of people think Berlin retains only a faint whisper of its 90s glory, with developers and foreign investors compromising creative freedom. Iconic clubs like Griessmuehle, Bar 25, and Tresor (to name a few) have closed their doors as neighbours pop up like Google and Amazon. Vacant lots become fewer and farther between as the city expands outwards beyond the borders of its former self, falling victim to intense urban development, gentrification, and globalisation.

Having arrived in Berlin in the early aughts, I saw what I believed to be the residual aftermath of what looked to have been a pretty magical time. It used to be normal that one would attend what they thought was an art opening, only to arrive in a curious room that simply could not be described. Was it an art gallery? Was it a bar? Was it someone’s living room? All of the above.

What struck me most about a lot of the images in the exhibition is how many times I looked at a photo and thought, that could have been taken today. Considering how much has already changed, many of the images harbour a timeless quality that is easy to latch onto and reminds us perhaps how much the city still has, for better or worse, to change.

OSTKREUZ agency’s last major retrospective, Ostzeit, was exhibited at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 2010. Now comprising 25 members, it has since become Germany’s most important and best known photo agency, its members working both as photojournalists and as independent artists as well as having founded a private documentary photography school with the same namesake that opened in 2004 in Berlin’s Weißensee neighbourhood.

Dream On—Berlin, the 90s Sep 14th, 2024 – Jan 22nd, 2025 C|O Berlin