I’d originally intended on spending the weekend in Miami for Art Basel —going from the focal convention center to the surrounding ancillary satellite fairs, attending art parties sponsored by credit card companies and high-end liquor brands, and trying to generally exhaust any available press-capital that my pass and virtual relationship to various PR art-people afforded me. But after I realized grades were due for my courses the Monday following Miami Art Week (meaning I needed to grade around 150 college Freshman essays over the weekend), I instead pragmatically opted to ride a bus from Orlando to Miami on Friday and leave late that same day.

In short, I spent around 16 hours in Miami Beach, going from fair to fair to write articles for two magazines covering Art Basel.

The Greyhound bus dropped me off at 6:15 am, a block from the beach, and after being denied entry to a CVS bathroom because it was “too early,” I walked to Miami Beach to see

“The Great Elephant Migration.”

The stunning installation was a life-sized horde of hyper-realistic elephant sculptures walking along the shoreline—constructed using lantana camara, an invasive weed in India that was evidently very sturdy, giving the sculpture a wood-like appearance. Already, it was apparent that “The Great Elephant Migration” was a crowd-pleaser, drawing onlookers before the sun had even risen. The sculptures had even brought unanticipated national press: A few days before, outlets reported that a couple had been caught having intercourse atop one of the elephants at night.

When I returned an hour later after sunrise, it had become a selfie destination, replete with influencer iPhone tripods and families posing in small units. The horde of elephants speaks for themselves on an immediate aesthetic level. They are technically impressive feats: mimetically accurate elephants (some in mid-step, trunks in the air), and the sheer size of the elephant group is awe-inducing. The elephants were available for sale, between $8,000 and $22,000, with all proceeds supporting conservation organizations and supporting rural villages in India.

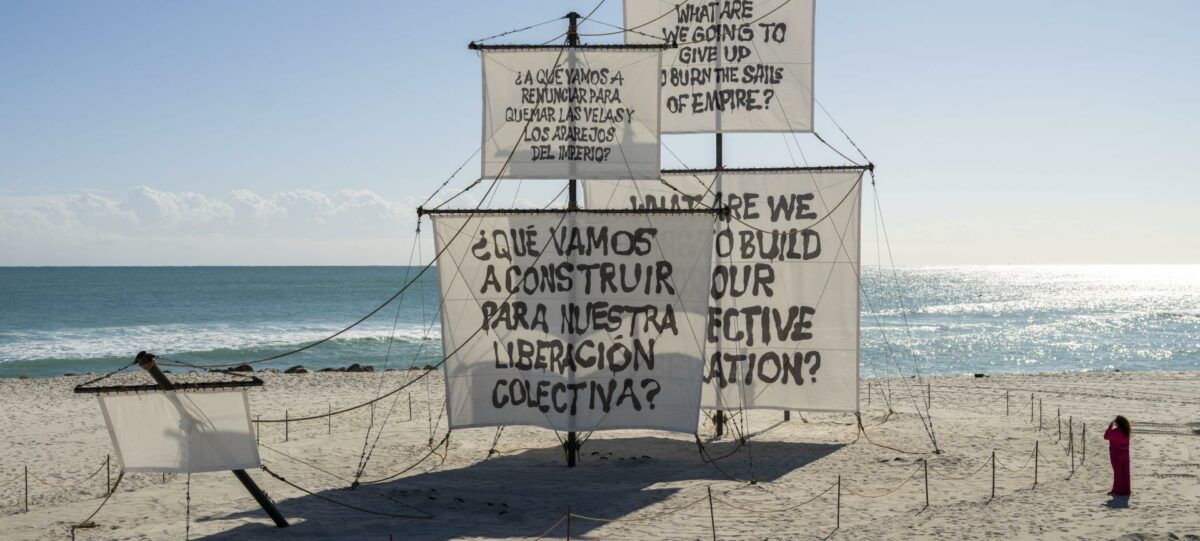

Next to the elephants was Faena Art’s large beach installation (sponsored by the prominent Miami Beach hotel), titled Seletega. The massive piece appeared to be a boat sunk into the shore, with only the wooden bow and the masts protruding from the sand. Using the masts as banners, the piece stated, “What are we going to give up to burn the sails of empire?” and “What are we going to build for our collective liberation?” in both English and Spanish.

While the installation’s text explained its significance, relating it to colonization and the American empire, the elephant sculptures remained the more popular attraction, for good reason—despite banners with revolutionary text held forty feet in the air, Seletaga seemed relatively banal next to the simplicity of the elephants.

Once I left the beach, I rode a Citi bike to the convention center to visit the weekend’s namesake fair, Art Basel Miami Beach. Inside, I wandered through neatly organized halls of the global galleries, shoulder to shoulder with the slack-jawed ultra-rich, stopping when a piece caught my attention.

In terms of sheer value, there were formidable pieces in this year’s Basel. Picasso’s Couple with Cup was Basel’s most expensive piece, estimated as worth $30 million. There were also pieces from American modern masters: Warhol, Haring, and Basquiat, worth millions each.

One of the most aesthetically compelling and conceptually thought-provoking pieces, in my view, was Self Portrait: Loyalty to the Past by Tavares Strachan. The piece is a powerful collision of cross-cultural and transhistorical images—with a photograph of the artist himself in a cosmonaut suit wearing an ancient African mask, astronauts in space, and a map of the stars in the background of the image. In the center of the piece are paragraphs in a small font, at times concealed behind other images, on disparate subjects such as archaic “astronomical computers” and the English philosopher Mary Astell, lending the piece a textual depth.

Although Self Portrait: Loyalty to the Past was certainly not the only collage in the building, but it was distinct in its clearly conceived deliberateness: reflecting on the (forgotten) past and its relationship to the future. The work enacted a collapsing of past and future—mythologizing a new time while reclaiming a past that had been hidden.

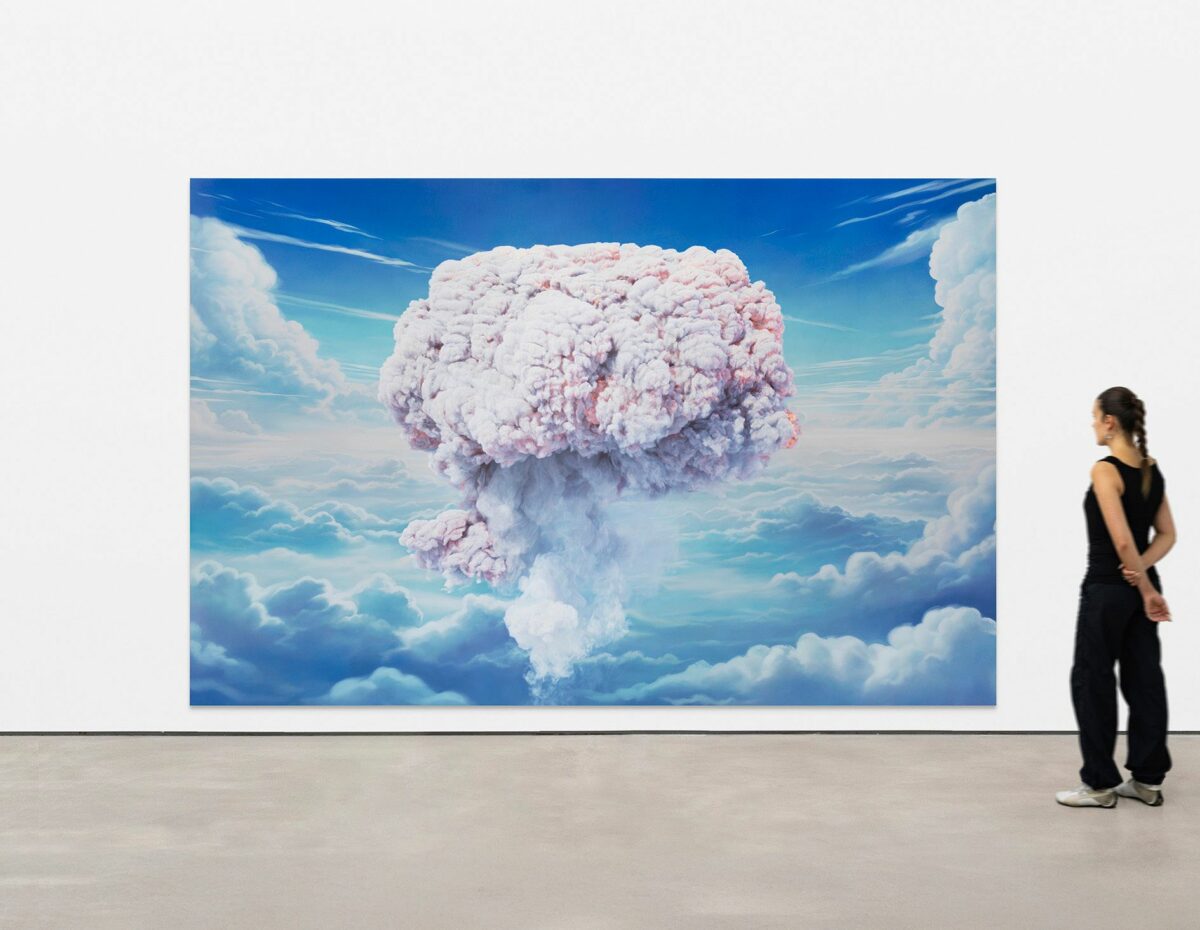

While Strachan’s collage was, conceptually, one of the most compelling pieces at Basel, another piece, which I returned to multiple times, was notable for its arresting formal elements. Untitled (1pm) by Anne Imhof is a large, detailed picture of a sky-view, with a plume of smoke rising above the clouds. At the margins of the above-sky plume are subtle, almost incandescent colors potentially indicating flames within the hidden interiority of the plume.

It was unclear what the plume exactly was, giving the painting an innate ambivalence: Was it a materialization of fiery divinity? Or was it a mushroom cloud from a nuclear weapon detonated on the Earth, with the carnage unseen outside the composition’s view? Either way, at a time when abrasive spectacle seems privileged over technical ability and beauty, a notable crowd gathered around Imhof’s painting.

Next, I went to Untitled Art Fair, a little over a mile away from Art Basel, directly on the shore of Miami Beach in an AC’d tent. Untitled Art, despite not having the same curatorial power as Basel, featured cogent work.

There were hundreds of worthwhile pieces, but one artist’s work punctured the noise of the exhibits—Alonsa Guevara. Guevera’s work was singular in the fair. The pieces, such as Welcome to My Garden, centered on the transcendence of nature: deep green foliage, citrus trees, a light blue-pink sky, and what appears to be an opening—likely referencing the entrance to the Garden of Eden. Like Imhof’s Untitled (1pm), Guevera’s paintings were a notable, and welcome, digression from the other work from the fairs.

With only a few hours remaining before my bus arrived at 10 pm, I went to Satellite Art Show.

Satellite Art Show was smaller than the major fairs, and the work was also the most varied—on the verge of disjointed and incongruous—but in a delightful way. The art and the venue itself were less self-serious and more sincere. In many of the exhibit booths, instead of gallerists, public relations representatives, and gallery assistants preoccupied on laptops (like the Basel fair), there were the artists themselves, happily discussing their work with visitors.

Satellite Art Show, an artist-run fair, represented the properly experimental and playful. There was nude photography next to straightforward landscape photography next to the unsettling final drawing by serial killer John Wayne Gacy (a clown waving goodbye) next to appliances staged in odd, non-utilitarian arrangements (such as a blender with rocks inside).

One immersive installation, behind a curtain, consisted of a fake gay nightclub with make-shift toilet stalls. Inside the stalls was a large “glory hole,” but instead of the expected appendage, there was a fresh ice cream cone—topped with whipped cream—proffered by an anonymous hand.

The most memorable piece was Vaper—Industrial Juice by artist Quinn Girard, at the entrance of the fair. The mechanized mixed-media installation consists of a disembodied head with wrap-around sunglasses and a hand gripping a vape—slowly, and perpetually, moving towards the head’s puckered mouth via an inner motor. Affixed to the bottom of the work were gas station sex enhancement pills that appeared to be complete non-sequiturs. Occasionally, the head blew out vape-smoke.

Although the sculpture is discrete in every meaningful way from a $30 million Picasso painting at Art Basel, it demonstrated, like the Satellite fair itself, that art’s origins are embedded in playfulness—all the artworks consisted of playfulness, just submitted through different forms and approaches.