The paintings of Francis Bacon have never failed to provoke a sense of unease. Exhibited currently in the National Portrait Gallery at a stunning scale, a wide collection of Bacon’s portraiture is being displayed in his posthumous show ‘Human Presence’, gathering over fifty of his works that memorialise and pay tribute to his closest friends, lovers, and his shifting relationship to his own body. His characteristic cultivation of the uncanny endures through the works on display, magnified by the density of his art on the gallery floor, and creates a palpably tense atmosphere in both a rare and richly affecting experience.

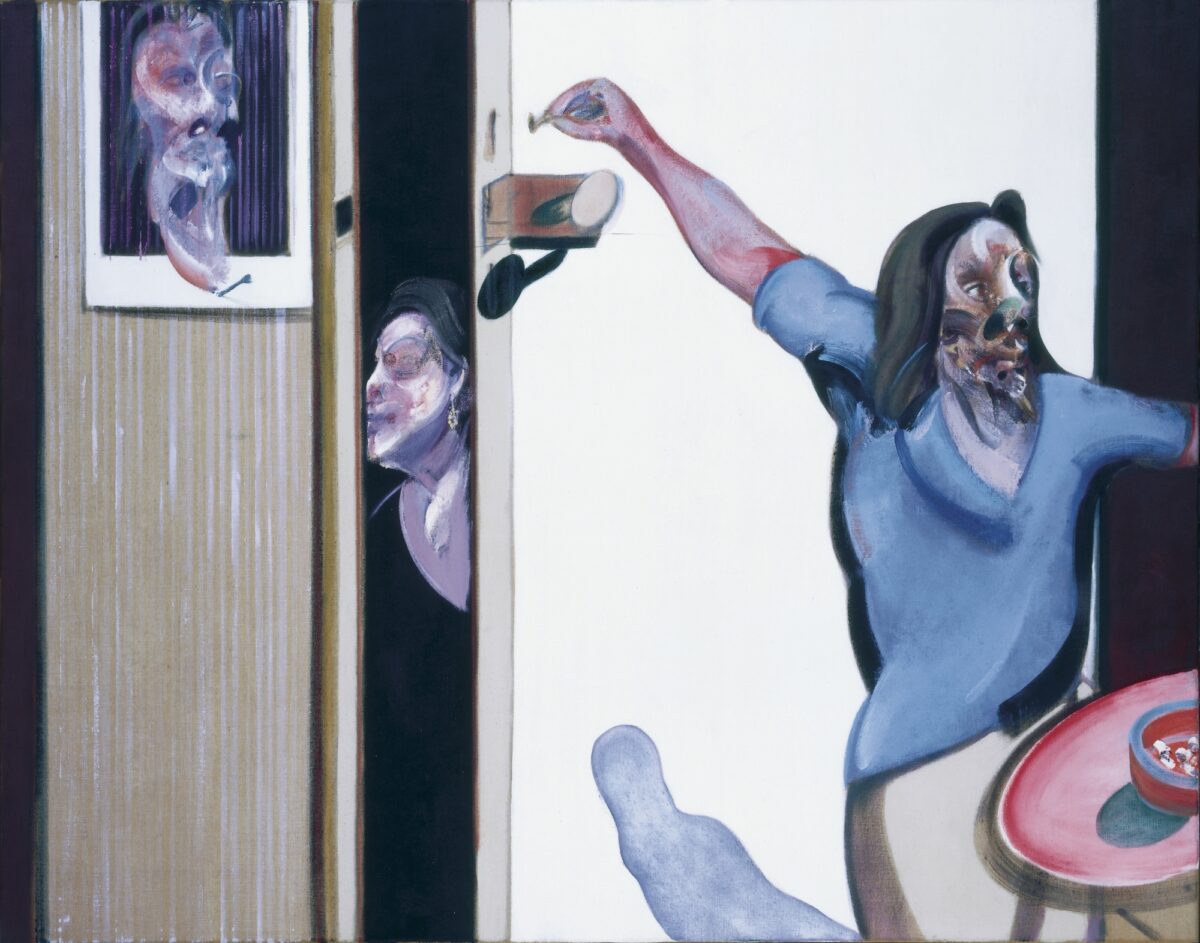

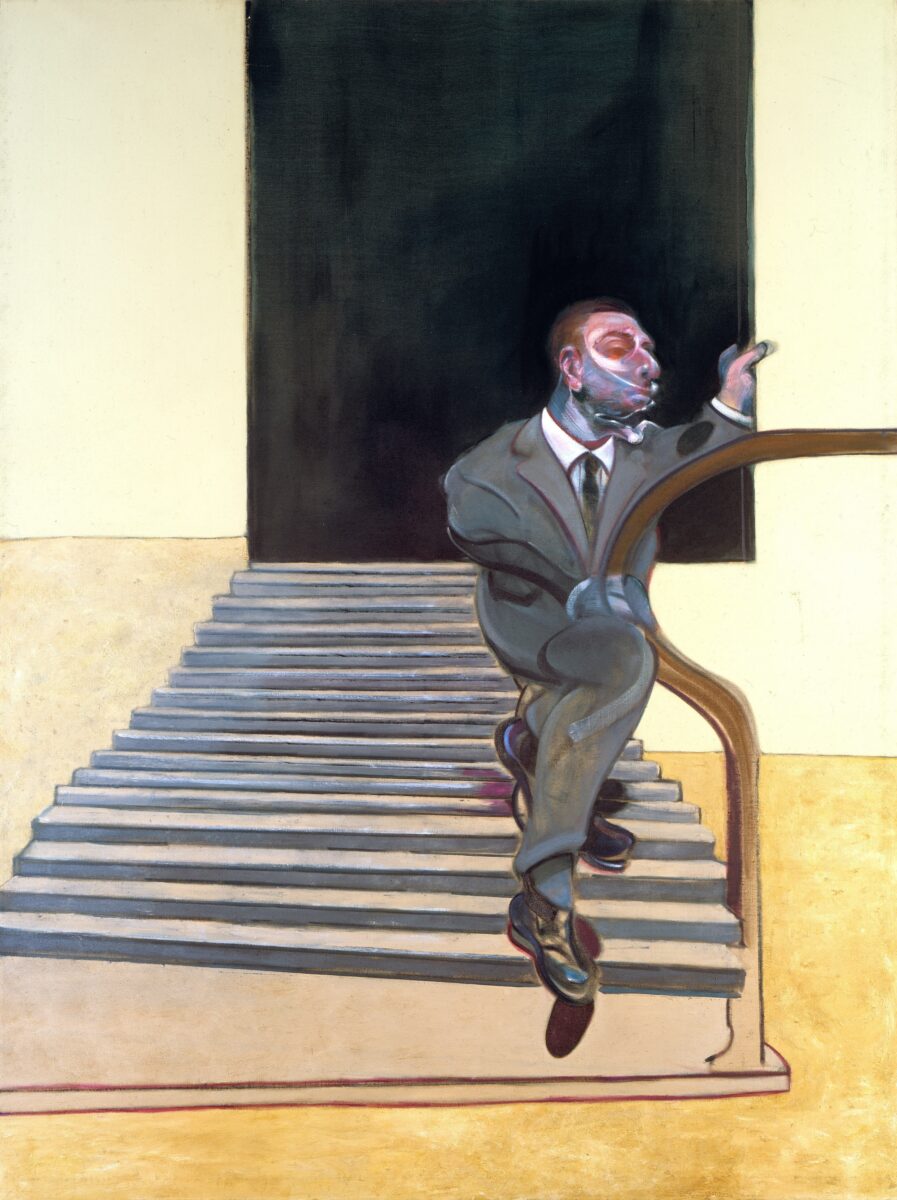

Despite the prolific number of figures adorning the gallery’s walls, the first thing visitors will notice is the lack of human faces amongst them. Exploring a work of Bacon’s, tracing the contours of the bodies depicted, from the gritty paints blended with sand to the bold swipes of colour that both form and distort their images, what stares back is usually closer to the face of a monster than a person. There are discernible features, lips, eyes, hairlines, but in every instance the face itself has been obscured, destroyed, and blurred as if caught in motion. There’s an inherent drama to the obfuscation at work, each smear of paint threatening to collapse the illusion of verisimilitude yet at once constituting the very forms that make up human faces, and this tension lends the paintings their power to captivate and disturb.

The violence of Bacon’s personal life is deeply interwoven into his mythology as an artist. Drawing on his tumultuous relationships, his work has been extensively covered for its obsessive motifs that take a shared orbit around the body being wrought out of shape. The subject of a force that has invaded the canvas, smearing these images of Bacon’s closest compatriots, at times nearly destroying them, his painting has been likened to both an act of violence and a showing of terrible vulnerability of behalf of the artist. To concede a sense of wholeness, of stability and recognisable identities, takes a tremendous act of courage, one that is seated in an ability, and a willingness, to allow oneself to be shaped by something outside of their control, and Bacon embodies this motion wholeheartedly.

In this respect, it’s hard to imagine Bacon as the orchestrator of his own work; it more closely resembles a kind of channelling. Though static, his paintings capture a sense of movement, a transformation, from one shape to another. Moreover, as they document Bacon’s own movements before the canvas, they delineate a history of translation, from the artist’s own perception to his embodiment of what he experiences. What emerges is the sense that he isn’t directly controlling the work, but speaking through it, marshalling its pigments and textures, allowing what he has felt to flow through the act of painting and simultaneously sharing this process with his audience.

Above all, Bacon’s portraits speak to the idea that he isn’t entirely in control, not of his subjects, not of their force, not even of himself. Swept up in a tide, a thick and viscous wash of emotion, this is undoubtably the source of the show’s uneasy atmosphere. The aura contained by the paintings, that seeps out of them, is accessed by a shared sense of permeability, both in the artist and his audience. Just as force enters Bacon, his paintings enter those who view them. A quality unique to his portraiture, it informs us of our own vulnerability, how easily we can be shaped, and how we share ourselves involuntarily with our surroundings, whether we want to or not.

Francis Bacon: Human Presence – 19th January 2025 National Portrait Gallery