The most significant sculpture ever created by Leonora Carrington will be offered at Sotheby’s this November during the Modern Evening Sale. Steeped in the artist’s rich visual language, La Grande Dame (The Cat Woman) is an ambitious and imposing work capturing the essence of Carrington’s creative exploration in the 1950s, touching on themes of feminine power, mythology, and spiritual symbolism. Appearing at auction for the first time in almost 30 years, it is one of the most valuable works by Carrington to come to auction.

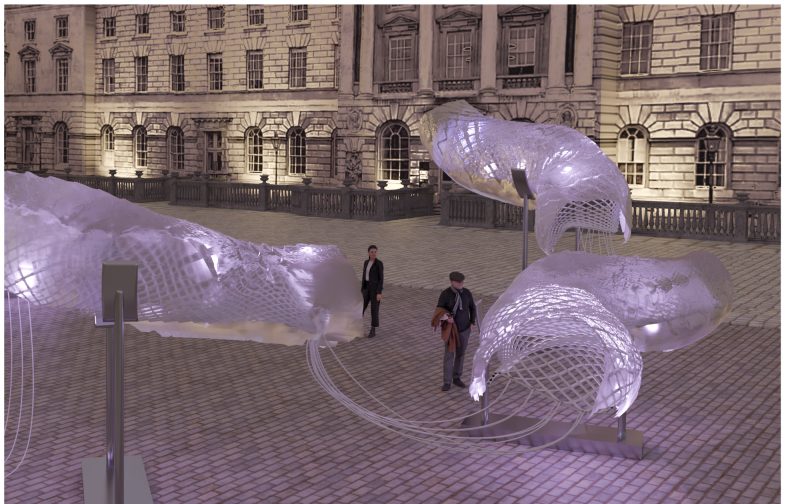

Born from a collaboration with the artist’s friend José Horna, the larger-than-life sculpture is adorned with bright, narrative vignettes painted by Carrington in her rich surrealist style, echoing both ancient and modern traditions. From her butterfly-like face and placid expression to her balletic arms and long, elegant fingers, La Grande Dame’s form includes a rich tapestry of cultural references, including ancient folklore and witchcraft, and evokes the Modern sculptors of the European avant-garde, through its gleaming finish, geometric forms, and masterful use of negative space.

In recent years, Carrington’s work, like that of many women artists of her generation, is finally experiencing market growth to levels that parallel her male peers, with Les Distractions de Dagobert, achieving $28.5 million at Sotheby’s in May. This marked a significant increase from her previous auction record of $3.3 million, set only two years earlier, establishing a new benchmark for the artist and affirming Carrington as the most valuable UK-born female artist, as well as one of the highest-selling Surrealist artists in history.

In La Grande Dame Carrington masterfully weaves together iconographies of the divine feminine from across the globe; her kaleidoscopic references touch on cultures ranging from the ancient Egyptians and Celts to modern Mexico. She makes reference to Bastet, ancient Egyptian goddess of protection, pleasure, and the bringer of good health, who is often depicted as a cat – echoing the grandeur of Ancient Egyptian statues with its imposing size, geometric stylization, and vivid symbolism. Below the goddess are two bound figures allude to the history of witchcraft, peacefully situated in a lush grove with flowers and animals emerging from their chests, symbolizing rebirth. Surrounding them, creatures from Irish and Mexican lore – foxes, skunks, rabbits, and birds – represent spirits traversing between realms.

La Grande Dame was long held in the collection of storied Surrealist patron Edward James; in years since, it has been widely exhibited across the globe, featuring prominently in exhibitions at the Serpentine Gallery and Tate Modern in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice among many others. Its prominence follows a resurgence of interest in the long-overlooked women artists associated with the Surrealist movement.

About the artist

Born in 1917 to an upper-class Catholic family in rural Northwestern England, Leonora Carrington’s upbringing was shaped by strict social expectations and the magical folklore – first introduced to her by her Irish grandmother and nanny. After a rebellious youth and several school expulsions, Carrington began studying painting with Amédée Ozenfant in London in 1936. That same year, she met Max Ernst at a dinner party, igniting a romance that led her to Paris, where she joined the Surrealist circle. Known for her sharp wit and dedication to painting, Carrington quickly made her mark with vivid, gem-like works populated by fantastical creatures, culminating in her participation in the Exposition International du Surréalisme at the Galerie Beaux-Arts in 1938. By 1941, after a traumatic separation from Ernst and a period of confinement in a Spanish psychiatric institution, she married Mexican diplomat Renato Le Duc, who eventually brought her to Mexico City – her lifelong adopted home.

In Mexico City, Carrington found a thriving art scene that combined local traditions with international influences. The city’s avant-garde was dominated by two groups: the celebrated muralists, who helped shape a post-revolutionary national identity, and artists like Rufino Tamayo, Frida Kahlo, and Maria Izquierdo, who explored fantasy and folklore. Numerous European artists and intellectuals, including some from Carrington’s Parisian circle, sought refuge in Mexico during the 1940s, joining a creative milieu that embraced her vision. Unlike New York galleries, which often sidelined surrealist women, Mexico’s leading gallerist, Inés Amor, championed artists like Carrington. In Mexico, she grew close to Remedios Varo, Kati Horna, and Gunther Gerzso, sharing in Surrealist games and creative pursuits.

In her later decades, Leonora Carrington continued to delve into mystical and surreal realms, exploring themes of feminine power, mythology, and transformation that had defined her earlier career but with an even deeper resonance. She immersed herself in the burgeoning feminist movement in Mexico, and her work evolved to reflect her engagement with political, social, and ecological concerns. Even as her health declined, Carrington’s creative output remained dynamic, and with her final works and words, left an enduring legacy as a luminary of Surrealism and a powerful advocate for imagination’s role in reshaping reality.