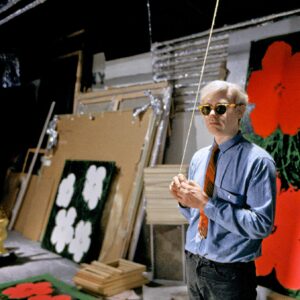

Gagosian-repped, YBA pedagogue, and Commander of the Order of the British Empire — one gets the impression that Michael Craig Martin’s many accolades could presuppose him. However, in the face of the kinds of lofty expectations that accompany a survey at the RA, the Irish-born artist puts humour before sobriety.

His retrospective opens quietly with early conceptual work. Radically minimal and theoretically complex, challenging pieces like Box That Never Closes and his well-known An Oak Tree – comprising a glass of water and a poem – set the stage for the rest of his oeuvre with existentialist reflections, prescribing the viewer with what is perhaps the most artistic feat of all: the philosophical enquiry.

After this requisite introductory review, the show becomes increasingly loud, unfolding as a progressively colourful and playful installation that incorporates Burlington House’s palatial interior architecture. Entire rooms are swathed in fields of vibrant magenta, cerulean, and a hue-shifting aquamarine that seems to change shade depending on where you stand.

Line drawings blown up to comical scale frame the historic architraves, as though the doorframe itself had been hallowed from the man-made, manufactured subjects. Other rooms remain white, allowing the canvas’ thick black tape silhouettes and acerbic colours to emerge from the wall with an emanation of confidence.

The streamlined and stylised subject studies continue, including a self-referential exploration of art history through a collection of replicas of Old Masters and a collection of Word Paintings: by developing a visual alphabet, letters are overlaid with corresponding images to create optical puns.

Visual elements converge towards the end of the gallery, where an immersive digital work engulfs a cordoned-off space. The twenty minute-long animation and corresponding soundscape includes over 300 objects collected over the course of four decades. Basking in the work feels like falling through the dark cracks of the artist’s portfolio like a tiny fly tumbling through a dizzying kaleidoscope of images that fall down into an offscreen abyss — recognisable, multifarious, and psychedelic.

The show has received a degree of mainstream criticism, but for reasons that seem to not only be uncharitable but also inattentive. Some local reviews have lamented the banality of his subject matter, suggesting scissors and lightbulbs are not interesting enough, implying that value lies not in the essence of thought but in the degree of immediate stimulation – as if to subject art to a higher standard of salience than life itself.

Lamps, ladders, and filing cabinets have been described as “everyday”, and “ordinary”. However, a crucial distinction the artist points out is that, humdrum as the objects may appear, what they are intended to be is familiar. It is familiarity that he plays with, using familiar objects to generate unfamiliar experiences — which, unlike formal object studies, are entirely subjective.

“People have strong emotional attachments,” he explains, “both positive and negative – to certain images, and these paintings bring that out.”

Familiar they are, and perhaps mundane, but only to a certain milieu of audiences. Who else would be so bored by these objects than those who have been burdened by their abundance? Whether boredom is an innate human sensation or just a malady of the modern world, being disinterested by pictures of iPhones and headphones indicates a degree of commodity-saturation and object desensitisation more than it does artistic deficiency.

Listening to Craig-Martin speak more about his work, it’s clear that his drawings are not even of unique objects per se, but rather representations of Forms.

Mixing his various drawings together to create compositions, he rarely draws the same thing twice, despite motifs being repeated continuously across both canvases and sculptures.

“Once you’ve drawn a safety pin, why draw it again,” he explains. “If I draw a safety pin, I draw it once. I use the existing images like templates — you will see the same image repeated over and over again.” In this way, his drawings are not drawings at all, but rather a set of symbols used in various compilations like a language, or systematic representations of Forms.

Plato first proposed Forms as the non-physical essence of things, or ideas of things. As Craig Martin suggests with his familiarity triggers, perhaps what is even more interesting than ideas or even ideals of things are the feelings that people carry around inside themselves about these things, and what this says about them, their life, and the notion of casting a gaze.

Much in the way Plato’s Formal essences remain unchanged, so do Craig-Martin’s symbols — created once and endlessly repeated to serve a purpose – that being to convey information, to represent a physical object, but necessarily to be interesting. In this sense, criticising the paintings for not being thought-provoking enough is almost as absurd as ignoring the privileged position from which such objects are ordinary or commonplace to begin with.

Setting aside the double standard in art — whereby some artists are celebrated for their glorification of quotidian objects and others condemned for it —perhaps it would be helpful to consider the uniquely visceral nature of object-oriented ontology. Or instead of pointing out what objects are ordinary, a better question would be what even is ordinary, and what makes it universal?

Michael Craig-Martin, 21st September – 10th December 2024, the Royal Academy of Arts

Main Galleries | Burlington House