Lin has performed for several years in storytelling events around London, including at the Moth StorySLAM, Bloomberg London Toastmaster, and Storytime London. She most recently performed a story with the theme of ‘elbow grease’ at the Moth at Richmix on September 11th. She has won competitions with her live stories about her unusual childhood growing up as one of four children under the One Child Policy in mainland China. She is currently working on writing a book about these experiences.

Xuetao Lin is an innovative writer and performer who weaves together traditional Chinese culture with contemporary narrative techniques. Her journey as a performance storyteller, filmmaker, Chinese tea ceremony performer and guzheng (Chinese harp) player shows her versatility as an artist. This background in a variety of artistic mediums has given her a storytelling style that is deeply rooted in sensory engagement and immersive experience.

As a storyteller, Lin unapologetically celebrates her cultural identity. She incorporates her native Hokkien dialect and Chinese artistic practices into her work, including music, poetry and the ancient art of the tea ceremony. Her storytelling is rooted in her personal experiences: she grew up in a tea-trading family, where stories were shared by the hundreds of guests who visited their tea table. Her practice draws on this communal yarn-spinning tradition, emphasisingemphasizing drama, humour and the outlandish.

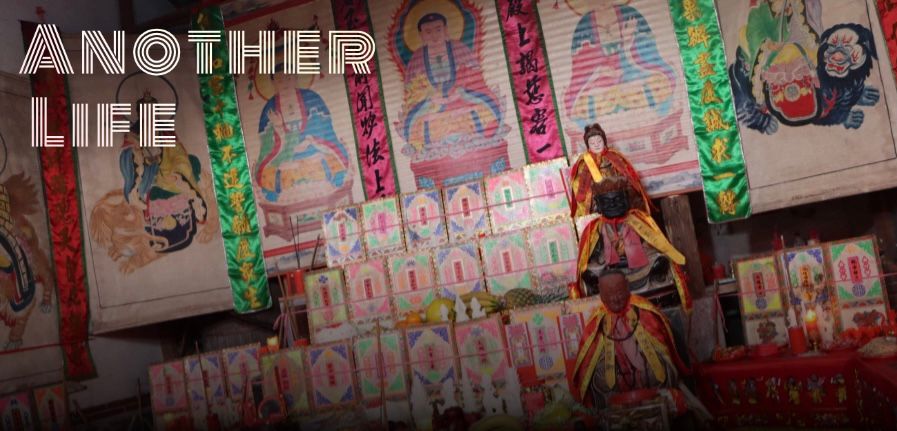

In her storytelling performances, she avoids flowery language and focuses on action and place to draw in the audience. Her past experience in documentary filmmaking has influenced her storytelling, giving her a talent for visual elements. Her documentaries, God’s Land and Another Life, explored ancient Chinese religious and funeral traditions – arts that are dying out in modern Chinese culture. Her passion for these traditions, like the tea ceremony performance, are also present in her storytelling, as she seeks to preserve and share knowledge about them with Western audiences.

One of the most surprising aspects of Lin’s storytelling is the way her portrayals of Chinese people break away from the outdated Asian stereotypes we are familiar with in UK media. Rather than characters who are passive or meek, her stories feature independent, strong-willed individuals who courageously push back against authority. Her stories often feature her non-conformist parents. These stories are personal but touch on universal themes like courage, family, and love that resonate with diverse audiences.

Like her parents, Lin also doesn’t conform to stereotypes. It is unusual to see outspoken women from mainland China on stage, especially one like Lin who swims against the tide, and she is blazing a trail in the live storytelling world.

You first experienced storytelling as a child at your family’s community tea table. What role did your upbringing play in shaping your creative expression today?

I was born into a tea family during the strictest one-child policy era in the mid-1990s in China. I am one of four siblings – forbidden children. My childhood was filled with uncertainty and I was sent away to live elsewhere with relatives several times. But I spent some significant years with my family, especially my parents and my sister. One thing I remember was the tea table – my parents have run a tea business since they were married. It was a lot of fun for me as a little kid. Our house was like an open tea market; every day, starting at 5 a.m., my parents were busy dealing with sellers and buyers, bargaining and closing deals. People came and went, and on the busiest days there might be a hundred or two hundred people.

People would sit at our large wooden tea table, helping themselves to different types of tea. The tea table fostered an organic community. People from different parts of China would sit and chat, often sharing interesting or bizarre stories. Our tea table was like an information hub. People shared information with each other – their business contacts, if there was a house for sale, how to get their kids into good schools, or where to find suitable partners for their adult children. I would brew the tea for people and listen to all the stories. Some were funny, some were boring, and some were so engaging that people lost track of time, holding their breath as the storyteller revealed the ending.

From a young age, I noticed that some people had a talent for telling stories. They could draw vivid pictures with their words, capture attention, or use dramatic body language and facial expressions. I learned about pace, flow, structure, playing with people’s expectations, and that ending with a strong punchline always works.

I developed a strong affinity for people. I wanted to understand why they said certain things and why they chose not to say others. Chinese social etiquette is all about saying what you want without saying it directly. The art is in the subtlety – the art lies in what hasn’t been said. You often find the answer there. A famous saying in Chinese culture is “It can only be understood intuitively, not explained in words.” This captures the essence of communication in Chinese daily life.

I was like a sponge, immersed in this natural storytelling club with fresh ideas and stories every day. I began to learn, to build my own style of storytelling, leveraging my strengths, including body language. My father is a well-known and dedicated tea master and taster, famous for his expertise in tea. His tongue is invaluable, he’s treated like judge when it comes to determining tea quality. People often brought tea to him to get a price quote – his opinion became a benchmark, earning him respect and reputation.

Naturally, he passed on a lot of knowledge and skills to me through daily teaching and apprenticeship. During summer holidays and weekends, I watched him gauge tea, interact with people, and persuade and influence them. It was like a masterclass for me. I was deeply drawn to it.

Later, when I left home at the age of nine, I discovered my passion for the traditional Chinese harp, the guzheng. In ancient Chinese culture, intellectuals often associated tea with music. Someone would play the guzheng or guqin to create the right atmosphere for drinking tea. It was a very ancient artistic lifestyle pursuit, different from modern Chinese culture.

I started practising with a professional guzheng artist and teacher when I was nine, and I still do today. The guzheng has 21 strings, and when I first heard my teacher play, I was amazed. I paused for five minutes, simply appreciating the music. The song was called (Battle Against the Typhoon), about how people protect their homes during an awful hurricane. The beginning was strong and intense. It made me feel nervous and serious but also determined, like those people. Later, the music became soft and tender like water once the hurricane had passed – feminine and beautiful. I was captivated. The guzheng created a strong emotional experience for me, which became another form of storytelling.

As an adult, I pursued storytelling by studying Media Communication and Journalism at university—the only major that allowed me to practice creative writing and storytelling at the time. I hope one day my writing and stories will be on screen.

You’ve performed at The Moth several times and won best story. What storytelling techniques do you use for these short storyslam competitions?

I believe storytelling is not about telling, it’s about showing – just like in music or tea performance, you have to evoke the five senses: smell, taste, texture, sound, and sight. If you say something is big, it doesn’t mean much. How big is it? Big compared to an egg, or compared to a giant ship? Detail is everything.

In my storytelling performances, whether I’m trying to bring my audience on an emotional journey or describe an event, I always do my best to integrate what I’ve learned from music training, tea performance, and storytelling techniques.

In your stories, the characters don’t seem like typical ones associated with Chinese people in Western society, where they are often portrayed as quiet, obedient, and collectivist. Your characters are independent and determined to pursue what they believe is right. How do you explain these differences?

I read news from different outlets, both Eastern and Western and politically left and right. It’s very polarized and stereotypical in my opinion. I’m often confused by what is reported in the media versus what I experience in real life – they are not the same. What is the truth? Independent journalism is rare these days.

I have a passion for writing my own stories and expressing how I see China, and what I’ve experienced, in a creative way. These life events are dramatic, full of tension, and rich in all sorts of characters. I feel they have value in presenting both contemporary and historical China. Life struggles, no matter where you’re from, reveal human nature and spirit. The expressions might differ across cultures, but at the core, they are the same, I believe.

Your documentary films have been on quite serious topics. God’s Land looked at religious practices, folk customs, beliefs, and rituals in China. Another Life was about life and death, documenting a traditional funeral ceremony that’s rarely seen in modern Chinese society. How does filmmaking influence your storytelling?

Visual storytelling is important; as the saying goes, “A picture tells more than a thousand words.”

In ancient cultures, life, death, and religion were intertwined, deeply influencing Chinese daily life, behaviour, and thought. It’s the root of Chinese culture. I want to dig deeper into it and find out more. To communicate with the West, I must first deeply understand my own culture and present it to the world as authentically as I can.

In Another Life, Buddhism and Confucianism are integrated. The monks were chanting to guide the soul to an eternal, peaceful place – heaven – while also recalling the soul to return and take belongings to the next life, ensuring they had enough to use in the next world.

Cross-cultural storytelling is an important part of your work. What do you see as the main philosophical differences between Chinese and British cultures?

The Taoist concept of unity between subject and object is important in traditional Chinese culture. In Taoism, the “subject” refers to a person and human consciousness, while the “object” refers to what the person observes (such as nature, the world, and deities). In Western thought, the subject observes, analyses, and transforms the object. In contrast, traditional Chinese culture emphasises unity between subject and object. It’s about mutual integration, intuition, and perception, forming a harmonious relationship with nature. As the saying goes, “When the eyes move, so does the heart,” and “Be a friend to the wind and rain,” “Be companions to fish and shrimp, and friends to deer.”

In Chinese thought, humanity and the world share the same principles and abide by the same “Dao” (the Way). This reflects the belief in “Heaven and humanity as one” and that the “Dao” follows nature.

In everyday life, Western culture tends to pursue truthful expression, valuing objective knowledge and precision. In contrast, Eastern culture often seeks goodness (in a practical sense, meaning usefulness). The focus is not on whether something is objectively right or wrong, but on whether it works – pragmatism. This attitude shapes Chinese people’s emotional characters: on the one hand, they are sensitive and emotionally rich, but on the other, there is a lack of scientific spirit – technological inventions exist, but the scientific ethos remains underdeveloped.

In your professional experience as a cross-cultural consultant, you work with Asian people who live or want to live in the UK or the US. How has your work trying to build bridges across the culture divides of these two places influenced your storytelling?

I think that ideology in the West is more about individualism and personal boundaries. In the East, there are more emphasis on collectivism, moderation and avoiding confrontation.

I would see my professional work as research for my artistic practice. Everyone has their unique story and upbringing, and everyone has their own life struggles with cross-cultural barriers.

Often Asian immigrant people find it difficult to form meaningful, deep connections with people from different countries. Or as an ethnic minority, we they can be ignored or neglected in social settings and professional settings. If you want to pursue a career in arts and culture or any other industry, it is hard to connect and sell yourself if you are not confident and are also being perceived in an unfavorable way.

I find that it’s important to help them find confidence and ownership of their own cultural identity and cultural heritage without feeling inferior to others or needing to conform to certain societal expectations in the West. It’s important to be confident enough to embrace who we really are and where we come from and fully accept that.

I think we don’t need to be leaning to any kind of extreme. Some people abandon their cultural roots to fit in or dismiss themselves to please others – but this is an expression of low self-esteem. Which in my view is not healthy and sustainable. I come from China. I love my family and friends, I love Chinese classical poetry and ancient wisdom, traditional arts and craft, I love the mountains and rivers and lakes in China, and I love Chinese food. And there are lots of good people like any other country, whatever you think of the politics.

If you ask about my ambition or vision, I’d say, I would like to start from me, myself, sharing my personal stories in my artistic practices, either through live storytelling, through my writing, my Chinese harp, or by performing Chinese tea ceremonies. I want to create a new narrative, and reframe who we are without any political filters. The cultural divides, differences, misunderstandings, hatred, and hostility whether covert or obvious – are increasing nowadays even with technology making information and understanding more available. My ambition is to leverage my storytelling and art performance to a global audience, put myself out there, and bring people to understand where we really come from in a personal and emotional way, that’s the impact I would like to manifest or have in my life.

You are working on a creative non-fiction book about your life in China, and you have performed several stories from the book at open mics. It seems that the audiences have responded positively to these unfamiliar stories, and to their emotional depth, even though the political context is alien. What role does politics play in your writing?

Well, I’d rather say these are human stories rather political critiques. I am not an expert in politics, and I have no intention to point the finger of blame. I rather let the audience decide and form their own judgement and have their personal feelings. It’s up to them to decide, I am not on a position to tell anyone how they should feel or think or force my opinions on others. Otherwise that would be a sort of dictatorship and narcissism on an intellectual level, wouldn’t it?

As a storyteller and writer, I don’t lie or make up things. And I don’t think we are defined by our struggles. As well as writing, I also love poetry and ancient traditional literature, and one of my favourite poet is Su Shi (also known as Su Dongpo). He wrote a famous poem, titled (Ding Feng Bo). Su Shi wrote it in 1082, during a low point in his career, while on a difficult journey with bad weather:

“A bamboo staff and straw sandals are lighter than a horse – what’s there to fear?

Let the misty rain fall; I’ll live my life as it comes.”

Despite his hardships, Su Shi has this carefree and optimistic attitude toward life, embracing hardships and challenges with equanimity and resilience. I find this to be the spirit of the characters in my book and my stories. There will always be a connection between contemporary China and historical China, as long as the spirit continues, and it is still alive.