Throughout a six-decade career, Jack Whitten’s work has bridged rhythms of gestural abstraction

and process art, arriving at a nuanced language of painting that hovers between mechanical automation and intensely personal expression. Focusing on Whitten’s paintings works on paper and sculptures from the 1970s, this exhibition showcases a juncture in the artist’s career, which saw him reject the gestural brushstrokes of abstract expressionism in favour of experimental processes and materials. Displaying Whitten’s long-standing interest in craft and woodwork, the exhibition also includes carved and assembled sculptures made by the artist during the 1970s.

The exhibition includes rare works from Whitten’s landmark, monochromatic Greek Alphabet series (1975-78), which was the focus of a dedicated exhibition at Dia Beacon, New York, from 2022 to 2023. This exhibition in London goes beyond the monochrome to also display Whitten’s experimentation with colour during this process-based period. In March 2025, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) will open ‘Jack Whitten: The Messenger,’ the first comprehensive retrospective dedicated to the groundbreaking American artist.

The black + white paintings have forced me to be cooler, imposed a limitation upon my work habit and

— Jack Whitten, December 1975

structure; forced me to tighten the visual concept; provided a personal framework of references plus a stamp of originality: THEY SAY WHITTEN.

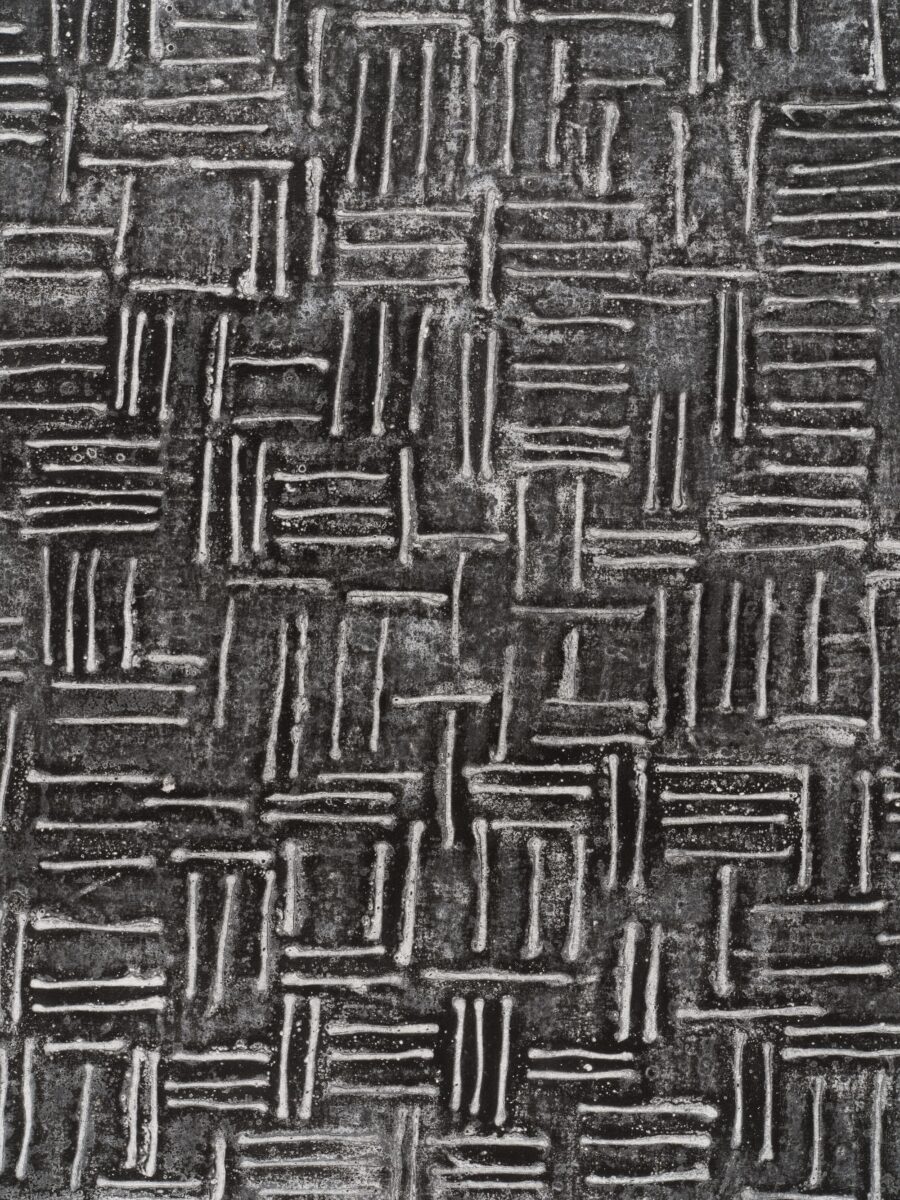

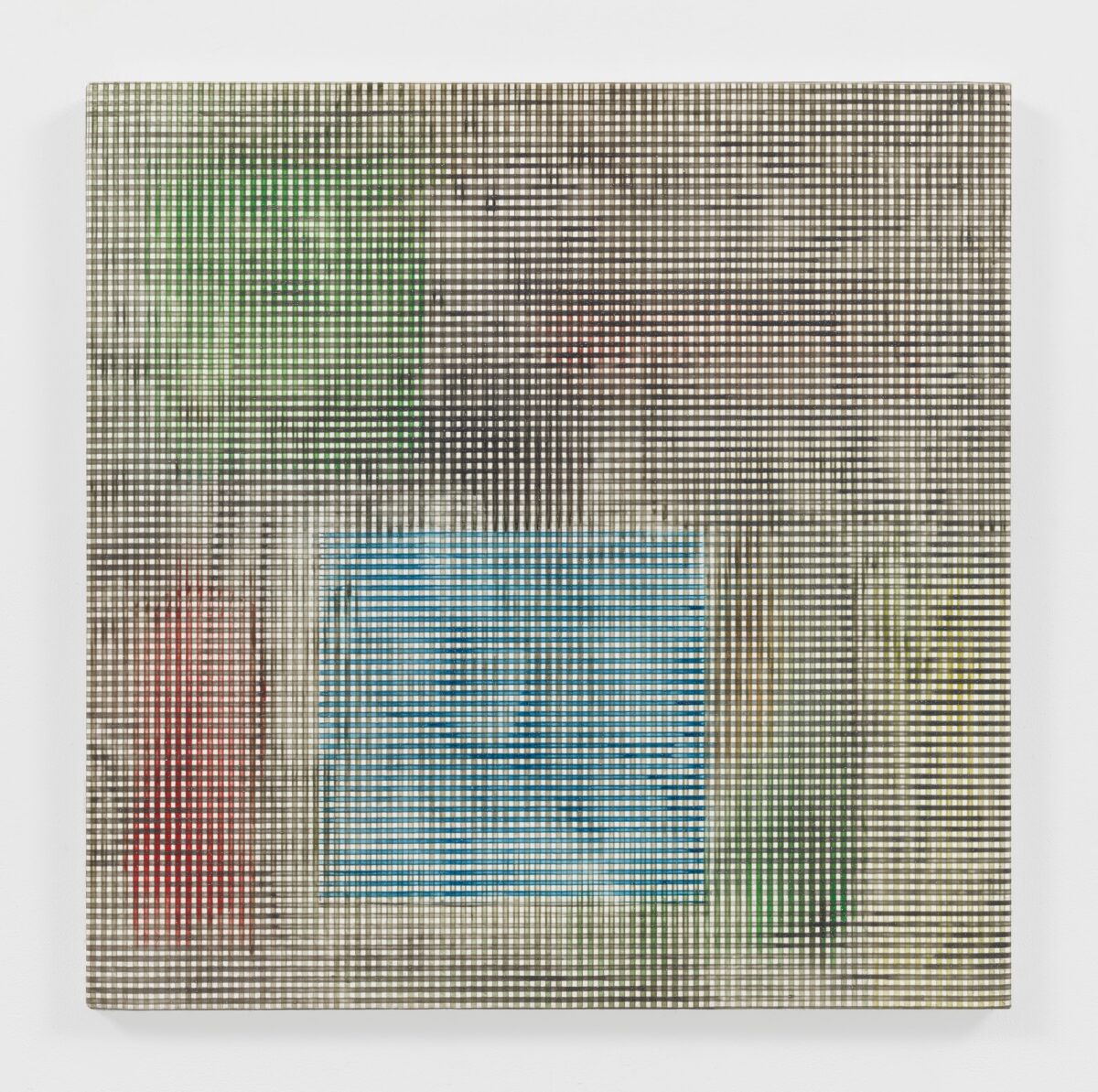

During the 1970s, Whitten made the conscious decision to remove all gestural mark-making from his work, switching gears to focus more on mechanical automation. At this time, the artist was inspired by his early training in craft and science—in particular, his ongoing research into quantum mechanics and contemporary imaging technologies. Removing the use of pens and brushes in his drawings and paintings, the artist instead made and used unconventional tools to create abstract constructions. As Whitten stated, ‘After several experiments, I built what I called the Developer, an analogy to photography, which was meant to rebuke the notion of touch.’ Employing rakes, rubber squeegees, saws and Afro combs, Whitten’s floor-based tool allowed him to spread and manipulate wet paint as he pulled the ‘Developer’ through the liquid surface. Working on the floor of his studio, the artist created a flat platform, the drawing board, on top of which he placed his canvas. Examples from Whitten’s DNA series (1979) are on display, where a painted, abstract background has been raked or combed to create a gridded pattern, a technique likened to deconstructing the photographic process, revealing—or in photographic terms, ‘developing’—imagery beneath an acrylic coating. A second technical innovation came when Whitten began to place a variety of flat found objects—metal sheets, pebbles or wire—beneath the surface of his canvas to generate ‘disruptions’ in the form of frottage. Reiterating the innovative nature of this period, Whitten said, ‘I like to think of my studio as a laboratory where experiments are conducted.’

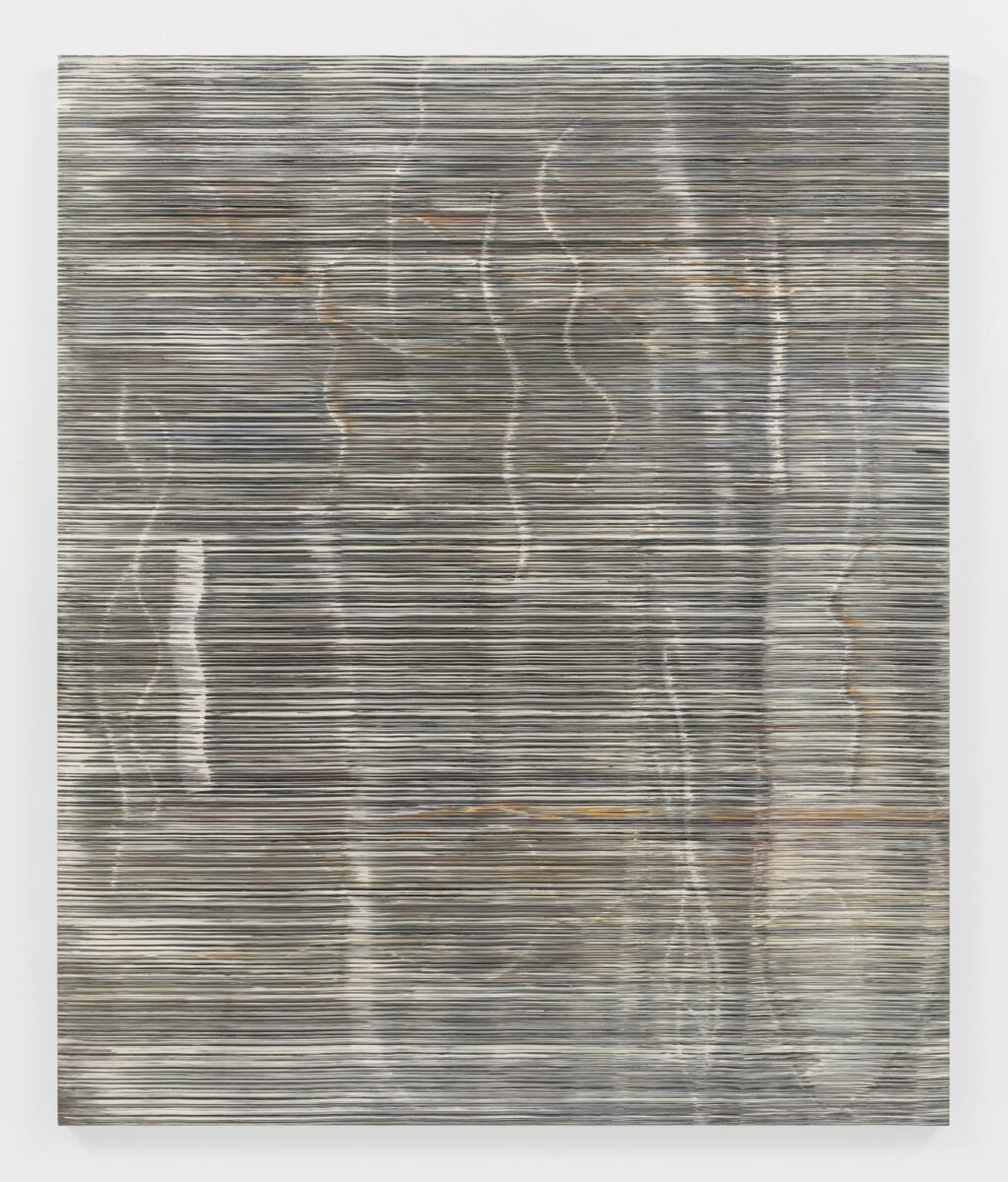

On view in the exhibition and exemplary of Whitten’s indirect painting methods are four works from the artist’s renowned Greek Alphabet series. Greece was an important influence throughout the artist’s career. Whitten’s wife, Mary, was Greek and the two first visited the country together in 1969. They would later decide to spend every summer on the island of Crete. Realized between 1975 and 1978, Whitten’s Greek Alphabet series consists of variations of predominantly black and white, abstract compositions ordered per the twenty-four letters of the Greek alphabet. Featuring repeated parallel vertical and horizontal lines that varyingly intersect, ‘Xzee III’ from this series recalls the complex meander pattern of ancient Greek art, inspired by extended periods of time spent in Crete. The ‘Greek Alphabet’ paintings, including other works such as ‘Nee II’ (1977) and ‘Gamma Group #1’ (1976), are not only technical and material explorations but deeply intimate works that speak to Whitten’s personal connections to Greece as well as his identity as a Black American. While making the series, Whitten studied modern Greek, which had an obvious impact on the work titles, many of which are phonetic spellings of letters in the Greek alphabet.

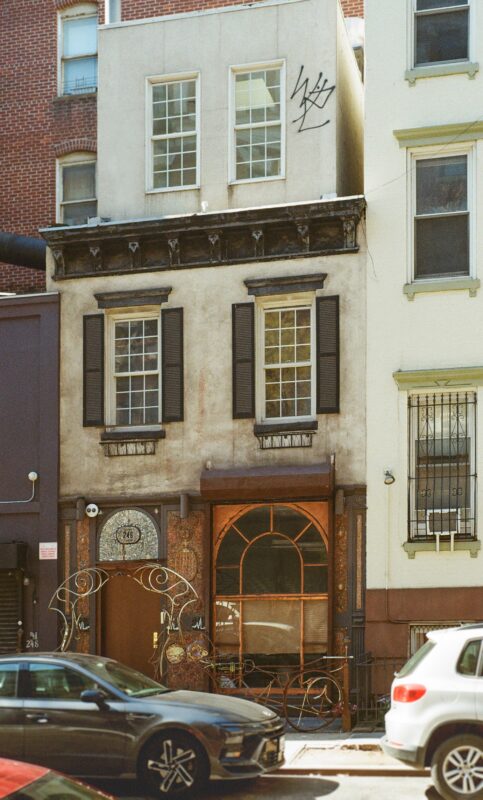

Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer © Jack Whitten Estate Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth

It was mainly in the Cretan village of Agia Galini that Whitten’s sculptural practice was carried out. Working in an outdoor workshop, these works consisted of carved wood, often in combination with found materials sourced from his local environment, including bone, marble, paper, glass, nails and fishing lines. Whitten’s sculptural works were private in nature, their creation an act of ritual as much as expression and were of great personal significance to the artist. This includes the sculpture ‘Reliquary For Orfos’ (1978) with an upright, slightly tilted posture recalling that of ancient Cycladic figures, made using black mulberry wood and housing the bones of the prehistoric-looking Orfos fish, which the artist hunted in underwater caves in Crete.

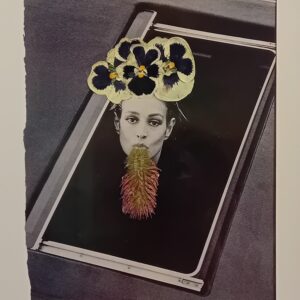

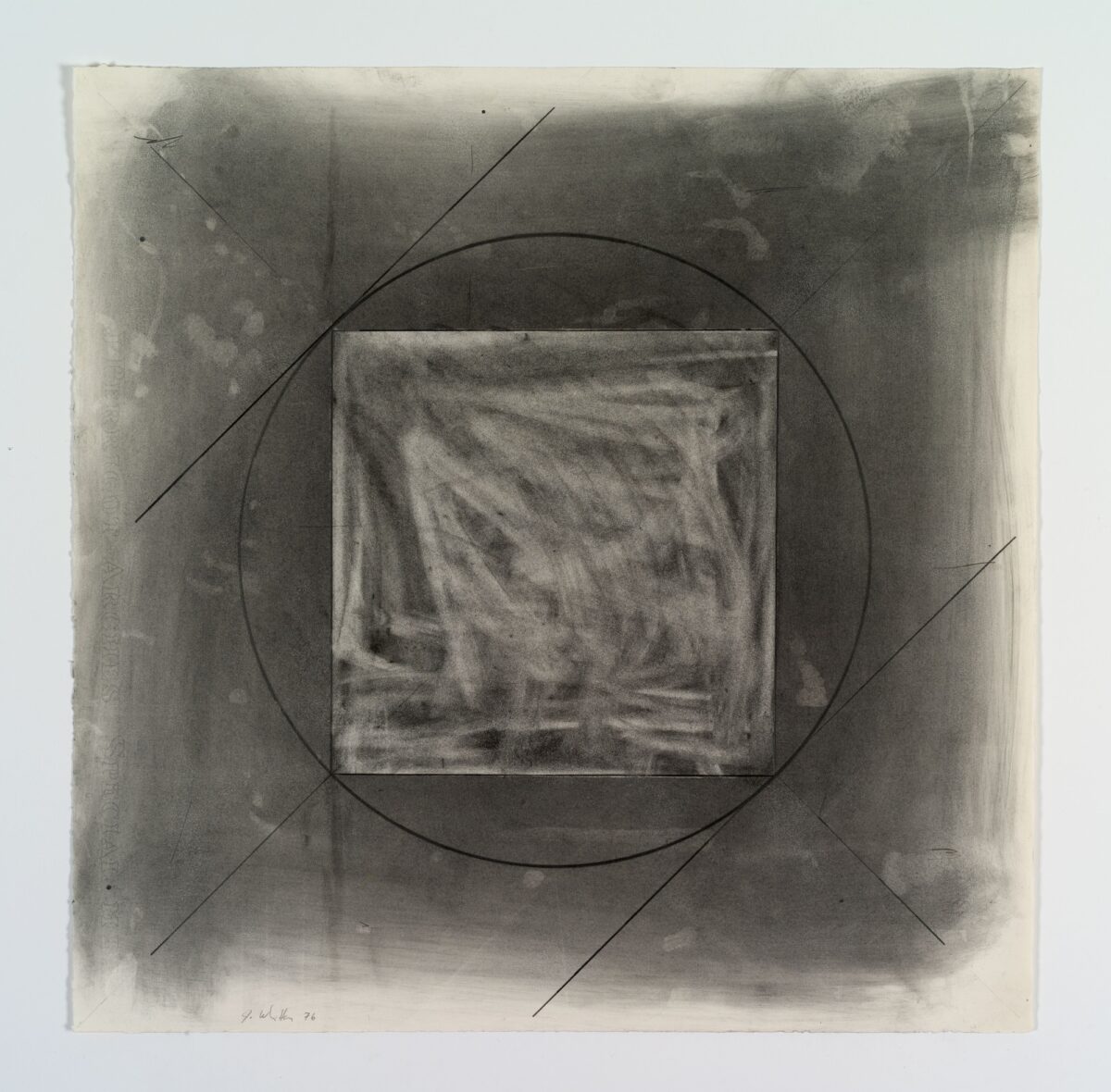

Whitten not only explored various artistic tools but also a range of mediums. Following a grant received by the Xerox Corporation in 1970, Whitten made a major discovery: dry pigment or toner needed no binder but was made permanent by applying heat. Relying heavily on the capacities of Xerox’s electrostatic printing technology, which allowed him to push traditional visual vocabularies and manipulate the idea of plane and space, the artist began applying toner directly to canvas and paper, utilizing heat lamps to set the images. With total abstraction and sophisticated restraint, ‘Xeroxed!, III’ (1975) is emblematic of Whitten’s investigative spirit of the decade.

In his paintings towards the end of the 1970s, he shifted from oil paint to acrylic. In doing so, the artist often mixed aluminium and metal powders into the paint to create different tonalities and to experiment with colour, visible in works such as ‘Formal Relay I’ (1979). Yet, his works of this period retained a pared down colour scheme in comparison with the bold and vibrant abstract expressionist works that came before. Citing this shift as a poignantly personal and political decision, he says, ‘I removed all spectrum colour from the studio … I reduced them down to black, white, and a range of greys. … you have to understand that in getting rid of all the chroma and taking it to black and white is not just a formal exercise. I’m very much aware of the meaning of black and white in American society, which informs who I am as an African American. The formal reasons for black and white are one thing but there are also the reasons coming out of the political situation, and I wanted to see if I could combine them.’ Mary Whitten highlights that despite works from this era being resolutely concept-driven and process-based, ‘Jack felt that the technical studies and experimentations were always working towards a goal of spirit and soul in the work. Never just the dry illustration of an idea.’

Jack Whitten. Speedchaser, 7th October – 21st December Hauser & Wirth London

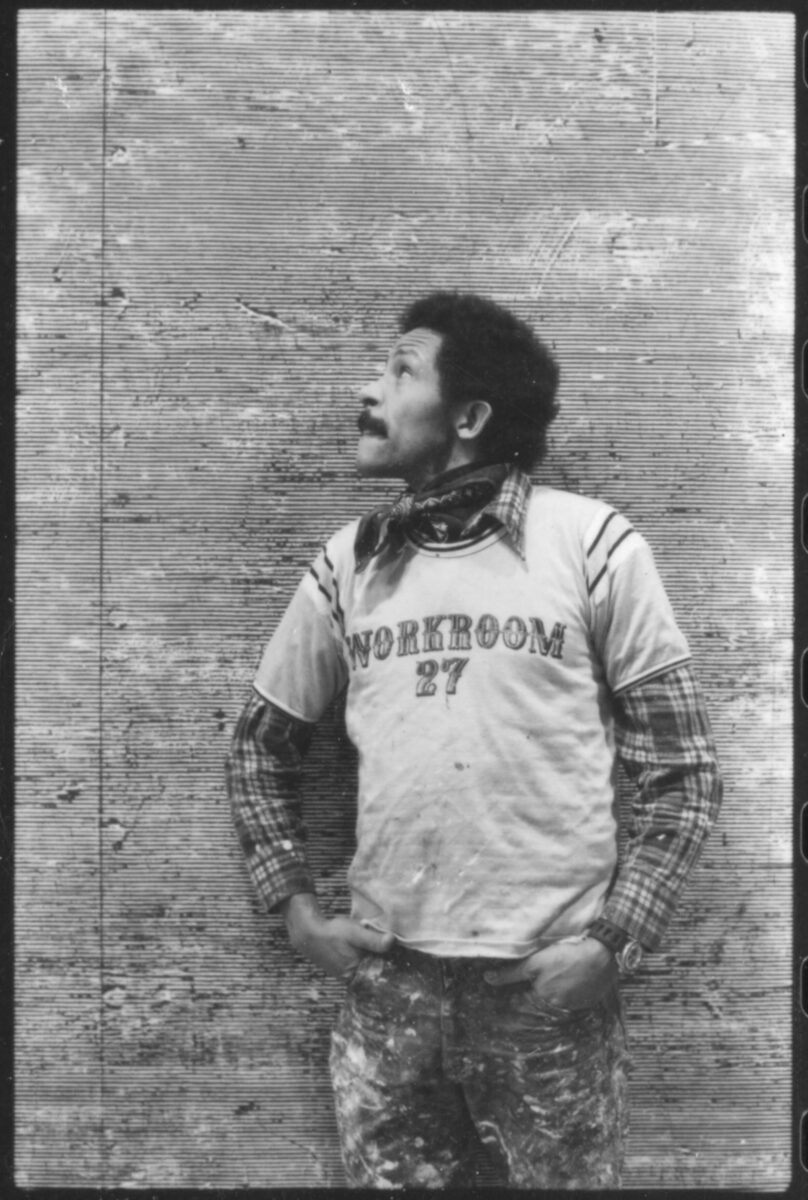

About the artist

Born in Bessemer, Alabama in 1939, Jack Whitten is celebrated for his innovative processes of applying paint to the surface of his canvases and transfiguring their material terrains. Although Whitten initially aligned with the New York circle of abstract expressionists active in the 1960s, his work gradually distanced from the movement’s aesthetic philosophy and formal concerns, focusing more intensely on the experimental aspects of process and technique that came to define his practice.

The subtle visual tempos and formal techniques embedded in Whitten’s work speak to the varied contexts of his early life. After a brief period studying medicine at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in the late 1950s, Whitten pivoted his attentions to art, first attending the Southern University in Baton Rouge before moving to New York and enrolling at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in 1960, where he earned his BFA degree.

In the 1970s, Whitten’s experiments with the materiality of paint reached a climax—removing a thick slab of acrylic paint from its support, Whitten realized that the medium could be coaxed into the form of an independent object. Whitten used this mode of experimentation to challenge pre-existing notions of dimensionality in painting, repeatedly layering slices of acrylic ribbon in uneven fields of wet paint to mimic the application of mosaic tessarae to wet masonry. Over the course of a six decade career, Whitten’s work bridged rhythms of gestural abstraction and process art, arriving at a nuanced language of painting, which hovers between mechanical automation and intensely personal expression.