On the occasion of Edinburgh Art Festival, Toby Üpson got carried away in the threads of Chris Ofili’s exhibition with Dovecot Studios.

To start with a bold statement: I do not like ‘the make of’ type exhibitions. Not moving nor sublime, wall texts and reportage never provide the romantic materialist in me with the space to get all wayward and dreamy; what I seek in exhibitions is never an ‘“interesting” …[full-stop]’. Chris Ofili’s exhibition, The Caged Bird’s Song, at Dovecot Studios (Edinburgh, until October 5, 2024) unravels that perspective. The Caged Bird’s Song soul focuses on Ofili’s 2014–2017 artwork of the same title — an artwork commissioned by The Clothworkers’ Company and first installed in Ofili’s 2017 exhibition at The National Gallery, London. As an artwork, The Caged Bird’s Song is a seven-metre long, three-metre tall, triptych tapestry in the altarpiece style. Hand-woven over three years in Edinburgh by five of Dovecot Studios’ master weavers, the exhibition marks the tapestry’s first public display in Scotland (hoorah!). More than just a detailed account of the weaving process, and a chance to see The Caged Bird’s Song in proximity to Ofili’s workings, the exhibition accentuates what I see as one of the work’s most poetic messages: how the realisation of a world space, one more vivid and vital, is a collective labour of love.

My enthusiasm for this exhibition, and the thing I call poetry, is wholly bound to the fluidity of Ofili’s work. Known as a painter, one who pushes against the formalities of this medium, Ofili often pictures figurative dream worlds which ooze technicolour futurity — a sense of hope and possibility, which Tina M. Campt has described as “the power to imagine beyond current fact and to envision that which is not but must be”. In its formal, functional and fictional details The Caged Bird’s Song drips with such passion.

Ofili’s working sketch for the tapestry is ambitious and allusive. Formed through freewheeling pools of watercolour and charcoal, here a moon-soaked beach shimmers into view; it is a setup all chicory-blue and silver-flake-green, violet and yellow, one infused with the spirit of Ofili’s chosen home in Trinidad. Floating central in this scene, two lovers recline. Boneless in form they curve in time with the haze of their surround, one plucking the strings of a guitar whilst the other sips a cocktail-like concoction. Ofili’s devil-may-care handling of his pigment echoes through these figures’ carelessly-cool facial expression; intoxicated by their surroundings, their downturned eyes deny my gaze, creating a sense of desire, pulling me past Ofili’s painterly fourthwall and deep into his liquid imagining. In something of a mise-en-abîme, this pair, and the panel they reside within, is flanked by another couple — the same couple perhaps; to my right, a male figure stands holding a caged songbird, my left a female lulls, entranced by the scent of a twiggy flower. With an echoing nonchalance, these disparate lovers pull back a theatrically thick curtain, revealing, if only for a moment, that beach-scape reverie. Again, with downturned eyes, these figures resist my looking, demanding that I become enwrapped, wanting of Ofili’s flowing vision.

The exhibition’s opening wall text states that this work is a continuation of Ofili’s ‘interest in classical mythology and contemporary demi-gods’. From what I know, these are often picturesque narratives with a moral sting in their tail — a sentiment expressed here through the dot-dash presence of Italian football player Mario Balotelli weeping high in the central panel’s bruise-coloured sky. Alongside these references, Ofili weaves cultural tropes particular to Trinidad into the tapestry’s design; the lush vegetation an obvious example, the caged songbird that gives the work its title a more pointed allusion — the keeping of songbirds being a popular convivial hobby on the island, something akin to the way football brings people together in the UK. For Ofili, this implied chirping acts as a metaphor for liberation and constraint, for the tensions innate to human life. Talking in a 2017 BBC documentary about the work, he asks “is the sweater song the song of the caged bird or the uncaged bird?”. At once this rhetorical musing has a simple answer: the uncaged bird, obviously. Reflecting, however, to live a truly sweet life surely one needs to be in the confines of friends and family, to be in the braces of a world abundant and vivid.

This sense of being held, welcomed into a space of equality outside-from common sense understandings of life, sits central to the futurity visioned in The Caged Bird’s Song. For Campt, the practice of futurity entails an interweaving of refusal and counterintuition; it involves going against the grain of a reality where certain lives — black, queer and female lives in particular — are actively devalued and denied a social existence. Ofili’s work fulfils this remit. With their downcast eyes and lulling posses, his figures sway in excess of any allegory, just glimmering from a world unencumbered, inviting me to dream that which “must be”.

Housed within a small cuboid chamber, the watercolour workings for The Caged Bird’s Song rest at, and as, the heart of the exhibition. Circling this space, somewhat typical constellations of photographs, informative vitrines, working mockups and mediating text panels ‘bring to life the process by which Dovecot’s master weavers transformed the colours, myths and magic of Ofili’s watercolour design’, to quote from the press release. Witnessing this material translation, I am blown away. Five weavers, 6,921 hours, 35kg of yarn, (at least) 2012 cups of tea drunk; bringing Ofili’s vision to life — 800 times larger than the original sketch — was a commitment, an utterly collective endeavour. This sense is further conveyed through video interviews and via vinyl wall quotes, which together paint a textual portrait of the tapestry’s emotive becoming. Indeed, by threading together the voices of the weavers’ alongside Ofili’s, the curators at Dovecot communicate a common belief bound deep within the tapestry’s very grains.

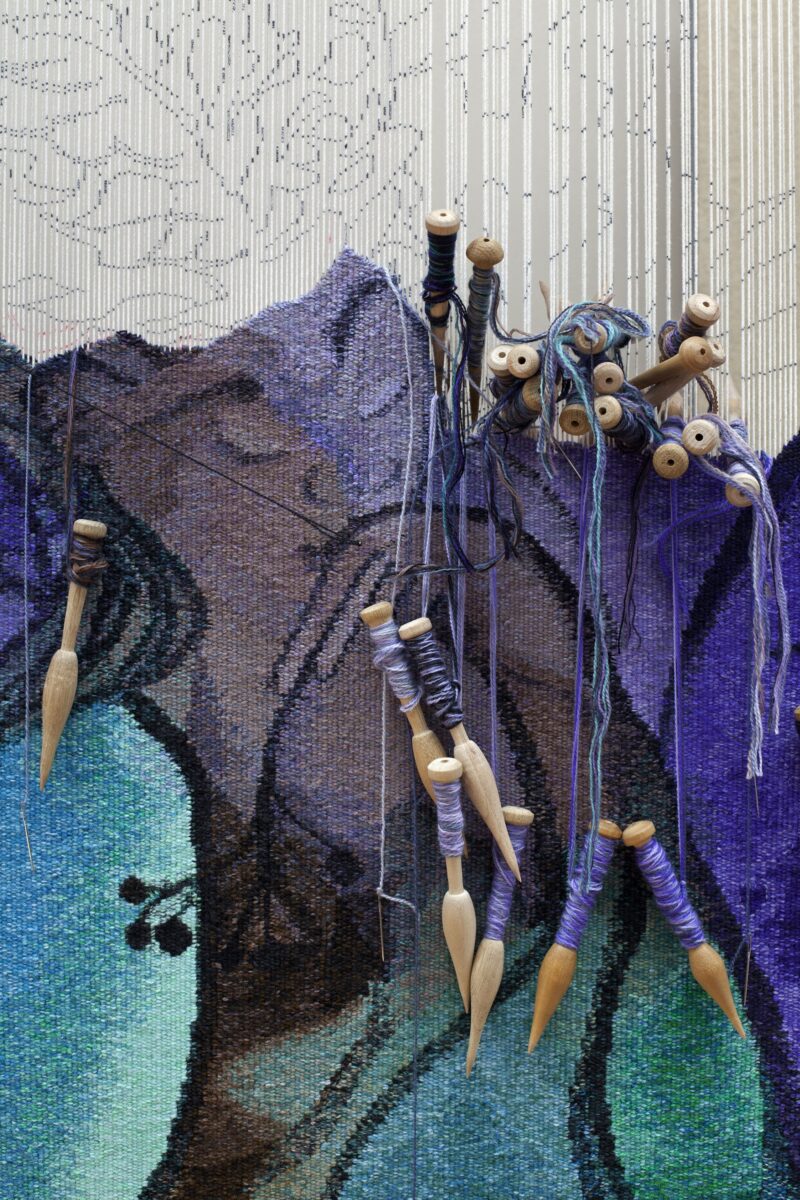

We get an incidental view of this conviviality via the in-process photographs of the tapestry that dot the exhibitions walls. Here, threaded bobbins, all brilliant in colour, drip over the becoming weave, recalling in my mind Ofili’s formal handling of weepy watercolour. It’s more than an interesting rhyme. As with his broader painting practice, for this commission Ofili set out to challenge the formal weaving process — the use of watercolour as an unstable media for the design is indicative of his sly ambition. Inevitably, it is through this meeting of incongruous worlds — the painterly and the quasi-mechanic, Trinidad and Edinburgh — that the profundity of The Caged Bird’s Song arises.

An act of trust, Dovecot’s weavers’ abilities to interpret Ofili’s design has allowed “that which is not” to live as a haptic vision of hope and possibility. The final tapestry hangs proud in a room of its own, all spotlit and magical, sheening like the finest of fine sublime apparitions. Sitting before the work I am left silent, wayward and dreamy. If Ofili’s design is misty and moon-soaked, the master weavers’ response is full on sun-splash. With over 250 different shades of yarn being used, in an array of colour and density combinations, the weavers have not only managed to echo the formal bleeding of the watercolour medium but to accentuate its painterly affect. With each thread and grain taut with its own vital energy, Ofili’s figures become so light and fluid; unfixed, they sojourn through their surroundings. And, as they weave, these lovers’ sound to me, guiding me into their paradise: a space, once a momentary myth, now a place which “must be”, one realised through loves’ labouring hands.

Chris Ofili, The Caged Bird’s Song until October 5th, Dovecot Studios