Inigo Philbrick, darling of the London artworld and fraudster extraordinaire, has something to teach us about how we deal with art. Orlando Whitfield has recently published his memoir, All that Glitters, detailing his friendship with Philbrick, which began when both were art history students at Goldsmiths. Having read the book, I’m more convinced than ever that we need people in the artworld who genuinely care about art and less who are in it for the money.

On the surface, Philbrick is just the kind of golden boy the artworld loves: handsome, confident, British-born and American-raised, well-heeled and well-connected with an intoxicating mid-Atlantic accent. At age 19, his privilege had landed him an internship at White Cube – which is impossible unless daddy is a client of Jay’s or your family is otherwise connected at the higher echelons of the artworld, which Philbrick’s is – thus beginning a professional relationship with Jopling that would lead to both a secondary market gallery and various private sales. From the moment privilege opened the door for Philbrick, he glowed like the hottest star in the galaxy, and then he worked hard at throwing it all away.

Philbrick was an enigma when I worked at White Cube. Whenever he visited the gallery we’d turn to one another and whisper in salacious gasps, “Look, it’s Inigo!”, as if Michael Jackson and Brad Pitt had entered the room. He was the chocolate on your cappuccino, he was the olive in your martini. I once engaged him in conversation about Theaster Gates and, although he was supposed to be out of bounds for us mere mortals, he was lyrical and passionate in the way only a true fraud could be.

His crimes began with the ambition of a boy who had never heard the word ‘no’. Whitfield recounts two occasions on which, while still a student, Philbrick conspired to acquire and sell Banksy’s that he had no right to: the first was on a door in Hoxton, which Philbrick convinced Whitfield to attempt to buy from the building manager, and the second was on the outside wall of a building in Clerkenwell, which he seemed to think they could arrange to have lifted off in the dead of night. Both plans fell through but they paint a picture of the type who will push the boundaries to make a sale.

Whitfield resists the temptation to paint Philbrick as a hapless chancer who got in too deep. He was a menace, driven by greed, spurred on by a confidence that can only originate in privilege. In one instance, while managing an art fund for billionaire, Marc Steinberg, he bought for $300,000, plus a finder’s fee of $150,000, a Rudolf Stingel painting that was so water-damaged beyond repair that the artist declared it destroyed and had ordered restorers not to work on it. Philbrick then sold the painting, which he documented as being acquired from Stingel’s studio, to Steinberg’s fund for $1.75 million, thus paying off the initial cost and pocketing the difference. Steinberg had never seen the work and certainly knew nothing of either the water damage or the fact that it had been struck off by the artist himself; indeed, the one time Steinberg sent an auditor to check on the fund’s holdings, Philbrick left the Stingel wrapped in polythene in its crate so the damage could not be seen.

Nervous that Steinberg would want to see the painting one day, Philbrick arranged for a joint venture to purchase it from Steinberg for $2.5 million. At this point, none of the buyers or sellers had raised issue with the fact that the work had now been sold on three occasions for less than its market value. One of those parties was Jopling, who, as part of a consortium with Philbrick, bought the work sight unseen from Steinberg. With Steinberg out of the picture and Philbrick now $2.5 million in profit, he told Jopling it had been held up in customs in New York, which brought him enough time to conduct the restoration himself, which he did in a garage in Mayfair less than a mile from White Cube. Following a period of obfuscation and tension while the work was going on, and then having magicked a condition report that testified to the work’s pristine condition, Philbrick and Jopling got in the region of $3 million for a painting that shouldn’t have existed.

In another instance, while also working for Steinberg’s fund, Philbrick falsely claimed to have bought a Felix Gonzalez-Torres work, Untitled (Welcome), that consists of a stack of everyday welcome mats. Having pocketed the money he’d been given to buy the work, Philbrick presented Steinberg’s business manager with a stack of mats he’d bought from a hardware store. Whitfield also reports an insanely convoluted situation towards the end in which Philbrick wanted to sell a Wade Guyton and a Christopher Wool that he co-owned with Jopling, who was not keen on setlling, so he claimed to have sold it for an irresistible sum to a fictional client, which played on Jopling’s weakness for a hefty profit, thus keeping taking control of the artworks only to sell them on again without now having to share the profits with Jopling.

And these are just the golden lies he told, the tip of the iceberg.

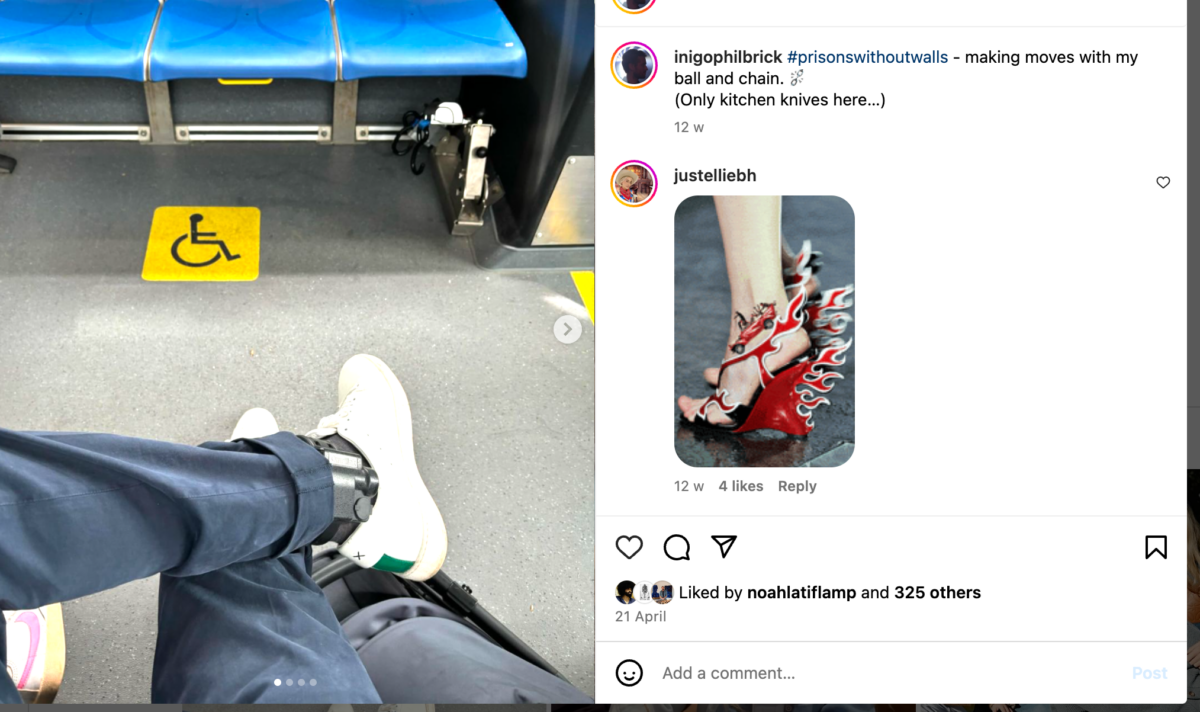

It all came crashing down in October 2019 when Philbrick, having relocated to Miami some years prior, defaulted on a $14 million loan. He fled the United States and went into hiding in Vanuatu, where he was arrested and extradited in June 2020. He was convicted of wire fraud in 2021, ordered to pay $86 million in restitution and sentenced to seven years in a New York jail, of which he served four. Philbrick’s crimes include selling more than 100% shares in artworks to multiple buyers, selling or using as collateral artworks without their owners’ knowledge, and falsifying documents such as condition reports in order to facilitate sales and inflate prices. When asked by the judge what motivated his crimes, Philbrick, suddenly honest to a fault, replied, “For the money, you Honour”.

The remarkable thing about Philbrick’s crimes is that they germinated from the quotidian sketchiness that the business of art thrives on: as an unregulated market that generates billions annually through the smoke and mirrors of handshakes, a world without contracts and awash with secrets, the artworld has created the optimum conditions for somebody like Philbrick to exist. The great surprise is that there were not significantly more before him. Nonetheless, art dealers and gallerists, despite operating in a misty world, tend to be honest and decent enough, more out of self-preservation than morality; if one little Inigo Philbrick, who mostly operated as a lone agent, can lose $86 million, imagine how much a big Larry Gagosian or Jay Jopling would stand to lose. In that sense, the art market is partially self-regulating.

Philbrick’s downfall, which differentiates him from many of his victims, such as Kenny Schacter, who lost $1.5 million, is that he never really cared about art. To be sure, and I know this from experience as well as anybody, there are plenty in the artworld – from dealers and gallerists to PRs and influencers – who don’t care about art as much as they care about the money it can make them, and while the artworld has made itself attractive to these people, and in some cases it has spawned them, most are not like that.

There is no denying that the artworld is driven by and obsessed with money, but the case of Inigo Philbrick shows just how wrong it can go when that’s all there is to it. Take that damaged Stingel as a case in point: somebody who valued it as art would have abided by the artist’s wishes because they would have understood that authenticity is not in the eye of the beholder, whereas Philbrick acted as if it were a mere commodity to be glossed over and stitched back together. He just didn’t understand art at all. Imagine if we were all like that – art would cease to exist.

At one point, Philbrick was making so much money – lunching daily in Scott’s or the Berkley, dining with £5000 bottles of wine, having Mayfair tailors and dealers on speed dial and travelling the world in business class – that even Jay Jopling told him it was too much, at which Philbrick balked. Like a petulant frat-boy who’d been told not to walk on the hot coals, he took of his loafers and socks and, with his Made in Chelsea girlfriend and unbeatable self-belief, strode out into oblivion.

Orlando Whitfield, All that Glitters: A Story of Friendship, Fraud and Fine Art (London: Profile, 2024) is available now.