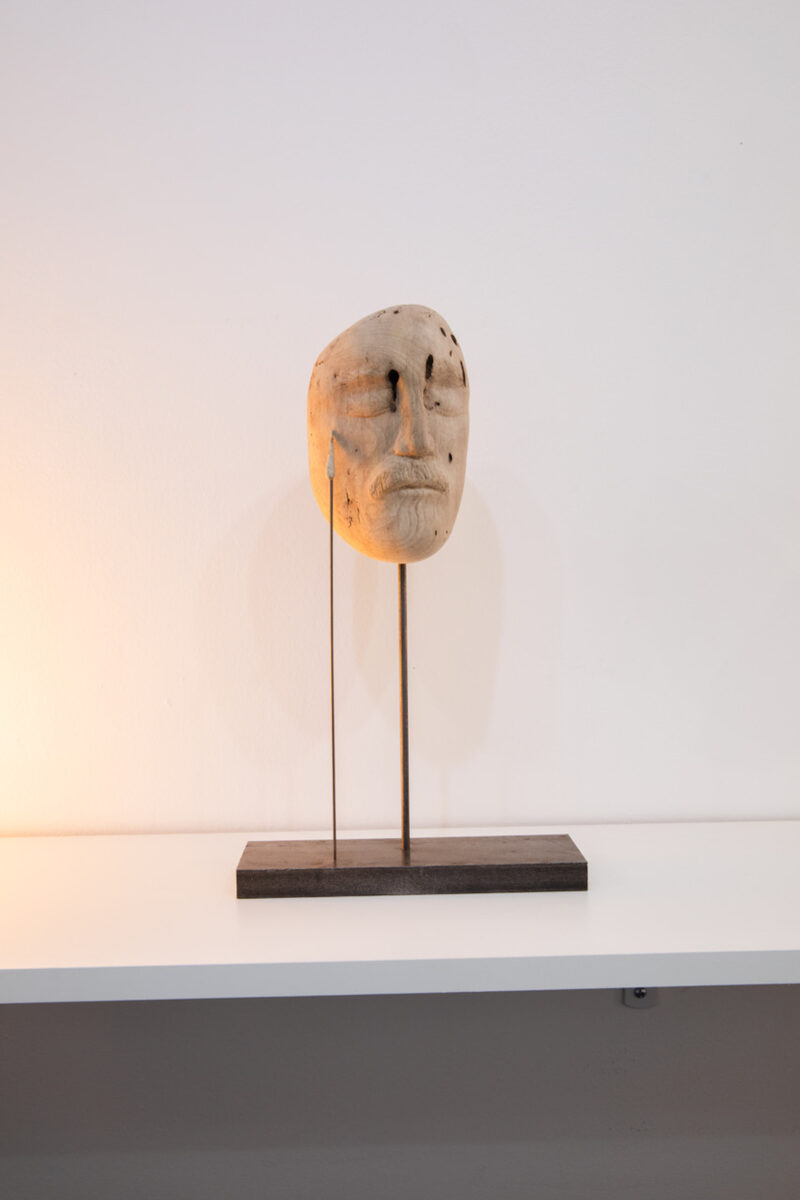

Schlomer Haus Gallery is presenting James Cherry’s San Francisco debut exhibition ‘Listening’, featuring a collection of driftwood carvings and buoyant lamps. For Cherry, the juxtaposition of light and earthly materials act as metaphors for the human experience, while the driftwood he found along Highway 1 since moving to the West Coast four years ago represents an organic amalgamation of friends, relationships, and loneliness.

Cherry’s lamps created from recycled materials have garnered attention from art and design collectors and are created using salvaged fabric mesh stretched across bulbous, amorphous or angular shapes. His driftwood sculptures play on the idiosyncrasies of the organic forms, and the interplay with the light sculptures strikes a balance between the pristinely refined and delicately handmade, with the lamps illuminating the driftwood sculptures and, in turn, the sculptures grounding the lamps, drawing the light and the eye.

James Cherry (B. 1996 Chicago, Illinois) received his BFA from Bard College and currently resides in Los Angeles. His work examines the relationship between personal and public information through material manipulation, while primarily practicing within sculpture and drawing. Meditative and repetitive processes are applied to both present and disguise intimate symbols of the human experience; transforming found objects to reveal private truths.

Lee Sharrock spoke to James Cherry for FAD Magazine.

Listening at the Schlomer Haus Gallery is your first San Francisco solo exhibition. Schlomer Haus Gallery say they are “committed to providing a platform for next-gen and mid-career queer artists, amplifying diverse voices and perspectives through the compelling works of underrepresented and emerging artists”. Is the ethos of the gallery what attracted you to exhibit with them?

I think I definitely appreciate when a gallery feels inclusive and approachable. I love that Schlomer prioritises diversity in its program, but I think it’s important to acknowledge the gallery’s placement in the castro of San Francisco. This has inherently allowed my work to live within a queer audience/ neighborhood. That type of direct connection with a place that is so enriched with gay history and life is a unique opportunity I’ve been really grateful to experience – it really drew me to wanting to work with the gallery.

Listening features a collection of driftwood carvings exhibited with the lamps that have become collectable items, which are made of complex manipulations and recycled materials. What made you decide to juxtapose two seemingly disparate styles of art: lamps with carvings of organic materials?

I like to work in opposites. I get bored in the studio pretty easily if I’m forcing myself to make just one type of work for too long. My way of pushing past this is to introduce something drastically different, but still in response to the last thing I did. And then sometimes I’ll work on them side by side. I have been working on these wood carvings casually for the last 4 years in between projects, trying to teach myself how to whittle and carve wood. Then when this show was offered to me, it really pushed me to finish them up and give them my full attention for a while.

When I was mounting them I started using a lot of steel, and that inspired me to introduce that material to my lamps after feeling a little burnt out on the carvings. I realized I wanted to make lamps that felt like they had a similar kind of character and impulsivity as the wood carvings, while respecting the steel material that now both the wood carvings and lamps shared. Even though the lamps and the wood are technically both made from “recycled materials” (the steel was salvaged from a nearby metal factories off-cuts, and the fabric of the lamps is recycled fabric I’ve held onto for years), I wanted the lamps to feel like the wood carvings synthetic counterpart. I think that contrast really lets each body of work breathe on its own, while relating each other with nuance.

You received a BFA from Bard College and through your artistic practice encompassing sculpture and drawing, you examine the relationship between personal and public information. What was your career trajectory after graduation through to your first gallery show, and do you have any tips for upcoming artists?

The trajectory was slow, at least in my mind. I saw kids I had gone to school with get solo shows a year after graduating, so I guess I felt insecure about that not being the case for me right away. I think when I stopped caring about that, I started making my best work— work I actually wanted to live with and wrestle with. I made my first lamp a month before leaving NYC to move to LA. It felt like the only thing I could make that wouldn’t impose on my shoebox apartment, but still felt like an honest expression of myself through sculpture.

I think my advice is to make work that feels like you’re being honest with yourself, because then you’re not afraid to be in conversation with yourself. You get to have a dialogue with the last piece you made that feels exciting to respond to, and in doing so, the work becomes more and more idiosyncratic. My work that is the most personal has always seemed to resonate with the most people, which leads to shows sometimes! But a lot of that I owe to just plain old luck because I don’t come from money or art world connections. Sometimes the right person just happens to look at your work.

What draws you to select the driftwood you find along highway 1?

I like wood that is light and feels properly dried out first and foremost. After that, it’s really all about the form, texture, and color of the wood. I’m not afraid to drag a log two times the size of me into my car if I know that it has character, if it has something about it I know I’ll want to highlight and respect. I’ve never been good at working from a blank canvas, so I really like picking pieces of wood that have that special thing about them for me to respond to, instead of trying work from a log that feels a bit lacklustre. It’s intuitive and more like a conversation in that way.

Do you react intuitively to the form of the wood you find, or do you have an idea in mind and work the materials to suit?

It’s definitely a mixture of both. I’d say 75 percent of the time I see a stick and it immediately tells me what it wants to be, but I’ve noticed that the more I look at driftwood the more personal the images I see in the wood become. I guess it’s like looking at the clouds, at first you might see a dog, but after 30 minutes you might see a mother rocking a cradle or a lizard surfing. Freud would have a field day with me at the beach.

Do you design your own narrative; is your inspiration purely derived from the creation of the organic abstract form?

Umm it’s definitely a conversation between my own personal narrative and trying to respect what the wood is asking for. Sometimes the decision to make something it’s subconscious. Sometimes I don’t quite understand my impulse at first, but it feels important enough to have faith in understanding it later. And then other times I feel like I create with complete certainty, at least until it feels done. Although I think I’ll always look at my finished work questioningly and very critically— work is boring to me if I don’t feel that.

What determines your choice of material used to wrap around the driftwood?

Sometimes I add my fibre clay (a blend of wood, paper, coconut husks, dust from my studio floor and other natural fibres). It dries like wood, it carves like wood too, I like that it mimics the wood in those ways. I don’t think sculpting with wood has to be reductive necessarily…I like the idea of making wood carvings an additive practice in this way. Sometimes the wood tells me it wants a little more material in a certain direction.

By using a light’s colour temperature, warm or cold tone, combined with the material, the light is filtered through impacts directly on space and environment and emotional response. How do you arrive at these choices, and is colour temperature a consideration?

It’s very rare that I add color to my work. I try to make decisions that respect the form first. With the lamps, I’m always thinking about how to hold a specific form I’m trying to achieve. What do I need to do to the fabric or clay or armature to allow this shape to become physical and permanent? Often times that is what governs the way light is diffused. How much wood glue, how much resin, how thick of fabric, how much sanding will it take to achieve the form I’m looking for— these are the questions I’m asking myself while working.

That said, I am sensitive to warmth— i like an object that feels welcoming and unpretentious, so I prioritize decisions that will make that happen with any object I want to make.

Do you manipulate the driftwood, sculpt it to your design, or do you keep true to the form you find?

It depends on the piece but I always manipulate it in some way, always.

By recycling found things that by definition have their own story, does your work intend to question what that story is, or are you reimagining the materials to your own narrative?

I think that recycled materials have a story embedded in them already, and it’s an opportunity to respond to the cues they’re already giving you. Recycled materials already had a life of their own, and there’s an opportunity to really highlight that through reuse. Sustainable design has the opportunity to tell stories that feel rich and reflective because of this: it feels like joining a conversation rather than trying to start one, which is more humble and natural in my opinion.

I don’t think so much about whose story it is that I’m telling (mine or the woods, the recycled fabric, the clay’s, etc), I’m more so trying to give way to the story that I see whether it’s mine or the woods. I like the ambiguity of who that story belongs to, and it takes the work outside of myself in that way which feels relieving for me, like trying my best to be a vessel for something else, but knowing a part of me will always be there.

Are you trying to say something about the environment through your work, or is it purely a material you use to react to create forms?

I think as a person I am very conscious of the environment and have a lot of respect for nature and supporting it. If that shows in my work it’s not necessarily intentional or something I’m actively trying to push, but it’s a part of who I am, so if it shows then I’m happy about that. Recycled materials are the materials I feel most comfortable using. I think the biggest freedom in using recycled materials is a lack of preciousness in our approach with them.

Getting to that point of confusion, where you look at material and can’t recognize what it is anymore is one of the most important things in my work— and I can only get there using recycled materials. There is a lot of freedom in using a material that has already been discarded. You get to experiment and take risks without it being so calculated and considering cost and waste as much as you normally would. This lets me play with material with a very childlike curiosity, it lets me try to push a material to the outer edge of its breaking point until it becomes something totally unrecognizable.

Where did your passion for abstract geometric sculpture come from?

I don’t think I’m passionate about abstract geometric form necessarily. Personally, some of my lamps feel quite the opposite of an abstract geometric form. Maybe they’re expressionist or abstract sometimes, but to me they’re usually very literal depictions of moments in real life, personal truths, personal demons, and conversations with myself, others and God.

Who or what is it that inspires you to create such organic and ergonomic geometric forms?

Sometimes it feels like the only way I can examine a big question in my mind is by making it into a physical object: a symbol. I think about sexuality, God, my friends, my family, love. These days my work feels very much about gayness and accepting that aspect of myself, and exploring my relationships with other gay men as friends and lovers, being part of a community that struggles in similar and dissimilar ways, what the edges of those struggles feel like, what certain types of discomfort and hatred look like, what different feelings of intimacy look like. I guess that’s just where my head is, especially for the work at Schlomer in the castro. I know it sounds nonspecific, but the everyday questions of life are my biggest inspiration for everything i make. And I’m in a heated pursuit of making these questions physical while I’m here on this earth.

What projects do you have coming up after the San Francisco exhibition?

My debut San Francisco solo show Listening is at Schlomer Haus Gallery until 27th April. In the fall I have a show with Tiwa Select in NYC, as well as a show of lighting in Portland with Spartan Shop. I’m also currently doing a series of sconces for an architecture firm I really love, Charlap Hyman & Herrero. I’m super excited about it all! it’s a busy year already, and I feel very blessed for that.

After this show in San Francisco with Schlomer Haus, it will be the first time in about a year and a half that I don’t have to immediately begin prepping for a new show. After my debut show in LA last year (with Noon Projects) I immediately began working on a solo show I was offered in Naples Italy with Galleria Solito, and then after that I did a huge series of lighting for an LA design company called Lawson Fenning. So now for at least a month or two I will be able to tend to my waitlist of commissions finally, and hopefully have some more room for new discoveries in the studio.

James Cherry ‘Listening’ – 27th April 2024 Schlomer Haus Gallery