A haunting spectacle from one of Britain’s great post-war painters, Frank Auerbach’s The Charcoal Heads at the Courtauld is a stirring reminder of how we can rediscover who we are in the wake of violence. As Head of the Courtauld Gallery, Dr Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen says, Auerbach’s charcoal portraits offer a new kind of ‘landscape’; one steeped in the smoking rubble of bomb sites, visceral human emotion, and a search for connection amongst the soot and debris of contemporary London. More than anything, the work exudes a will to life in all its forms, even those hewn from severe circumstances.

Auerbach’s main group of charcoal portraits on show date between 1956 and 1962, having been created alongside his landscape works of post-Blitz London. After studying at several art schools, Auerbach took his first leap forward as a professional artist during this time, working for extensive periods to sketch those closest to him, creating a series works which all bear his distinctive interpretation of charcoal sketching.

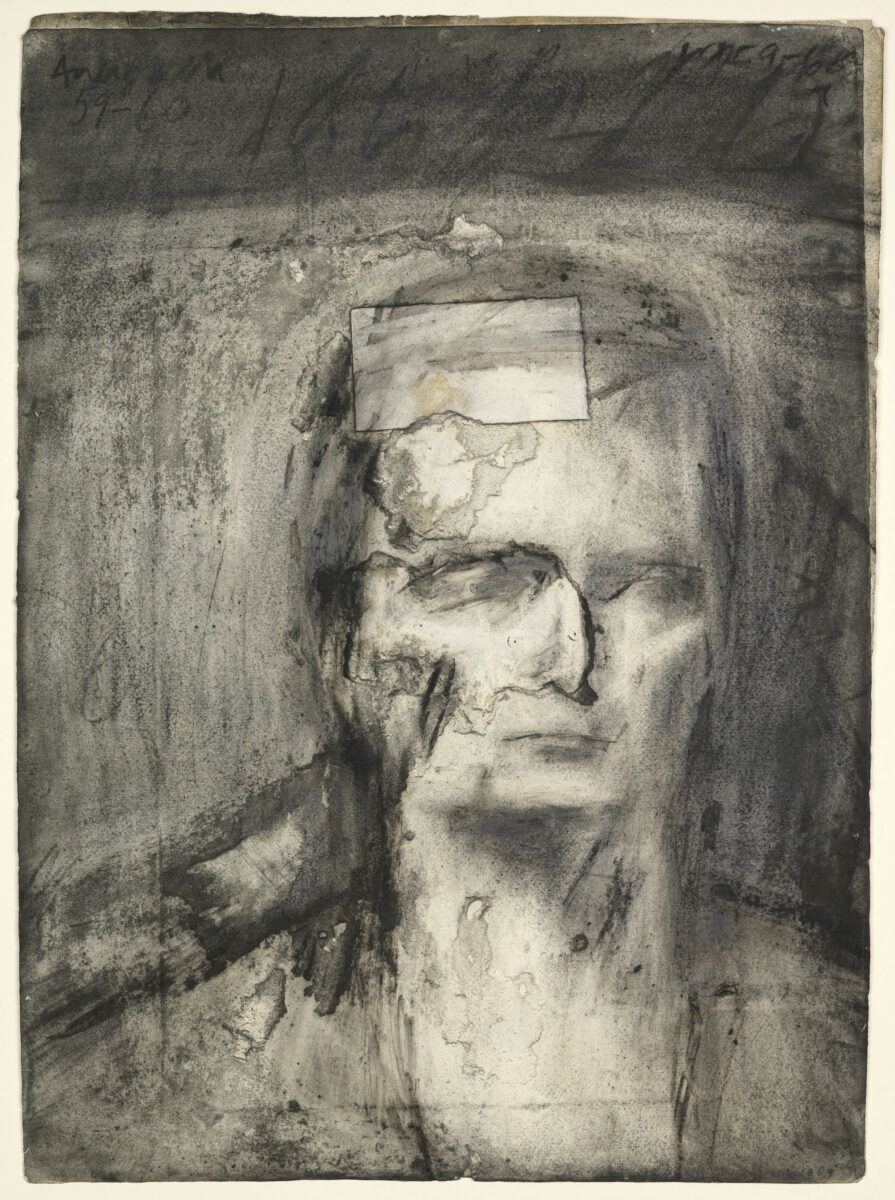

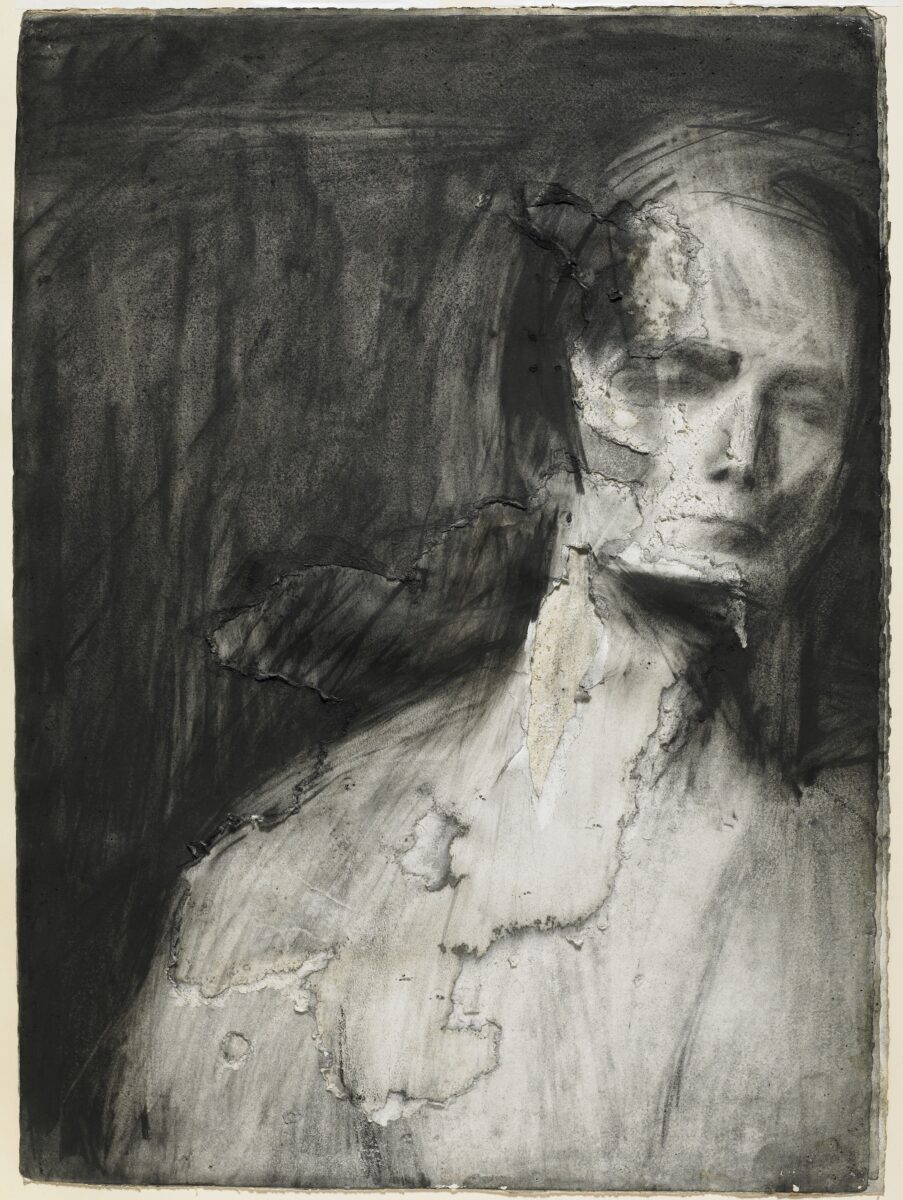

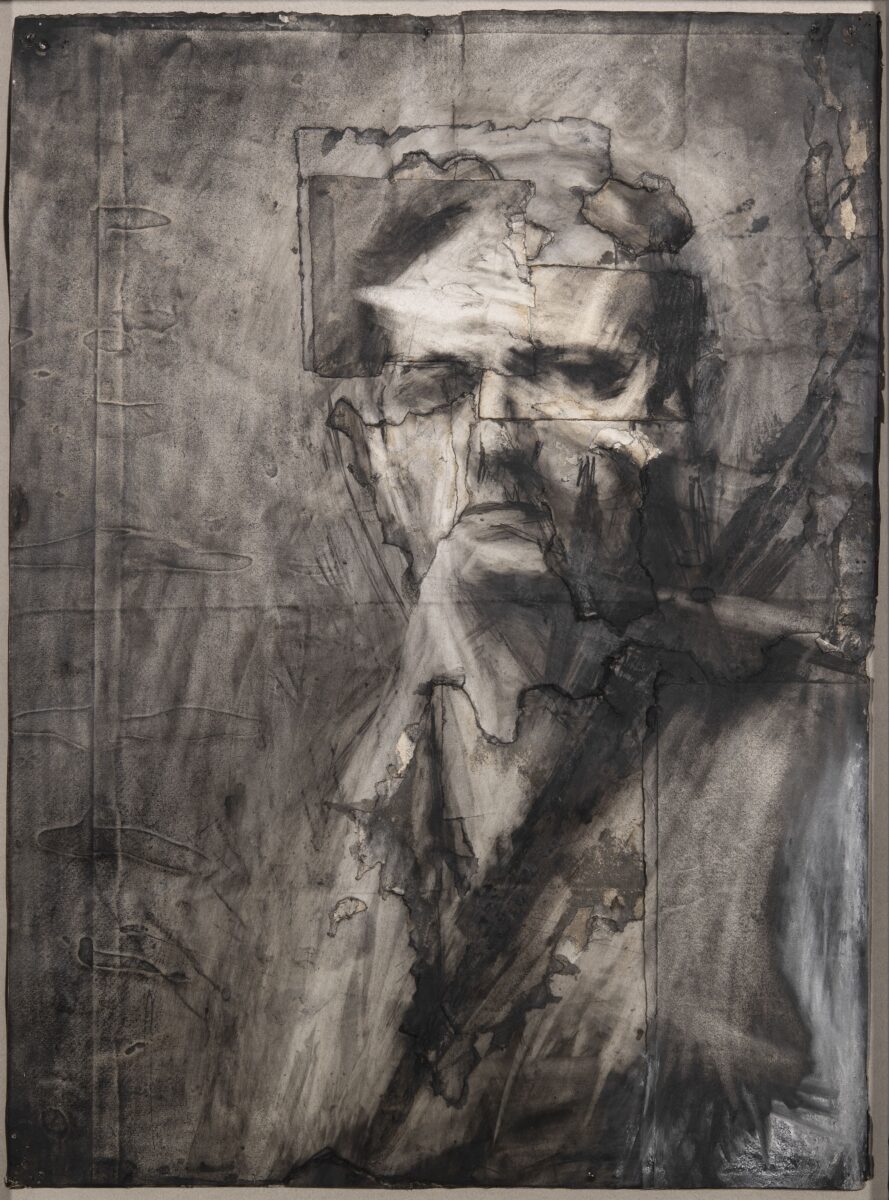

The majority of pieces exhibited depict Stella West, Auerbach’s romantic partner for many years. Featured in a variety of poses, West sat for the artist on innumerable occasions, often late into the night, only for the artist to remove much of his work by eraser. During the next sitting, Auerbach would then work with this already marked paper, on which rested the remains of what became several previous sessions. Over time, this relationship between sketching and vigorously erasing his drawings required new grafts of paper to be attached to each piece, building up complex and nuanced portraits of her through the energetic means by which they were produced.

The intensity of this process mirrors the impact of Auerbach’s final works, the images holding a ghostly yet immovable quality that lingers under the many layers of creative energy on show. A palimpsest that dictates the sum of human effort to create art, to capture a figure, and to render form despite all adversity, is a remarkable statement to what it means to create after conflict. The works stand as witnesses to terror, passion, and action, but most of all to the freneticism of his portraiture.

Despite the majority of works on show being monochromatic, there is a powerful vibrancy in each of Auerbach’s representations; particularly when considering the eyes. The figures’ lines of sight are largely downcast and fixed on some point other than the artist; a point that is beneath them. They are captured with an almost photographic quality in this way; as if occupied with other things, drawn into other thoughts, and imbued with a subjectivity that speaks to the full potential of the relationship between artist and muse.

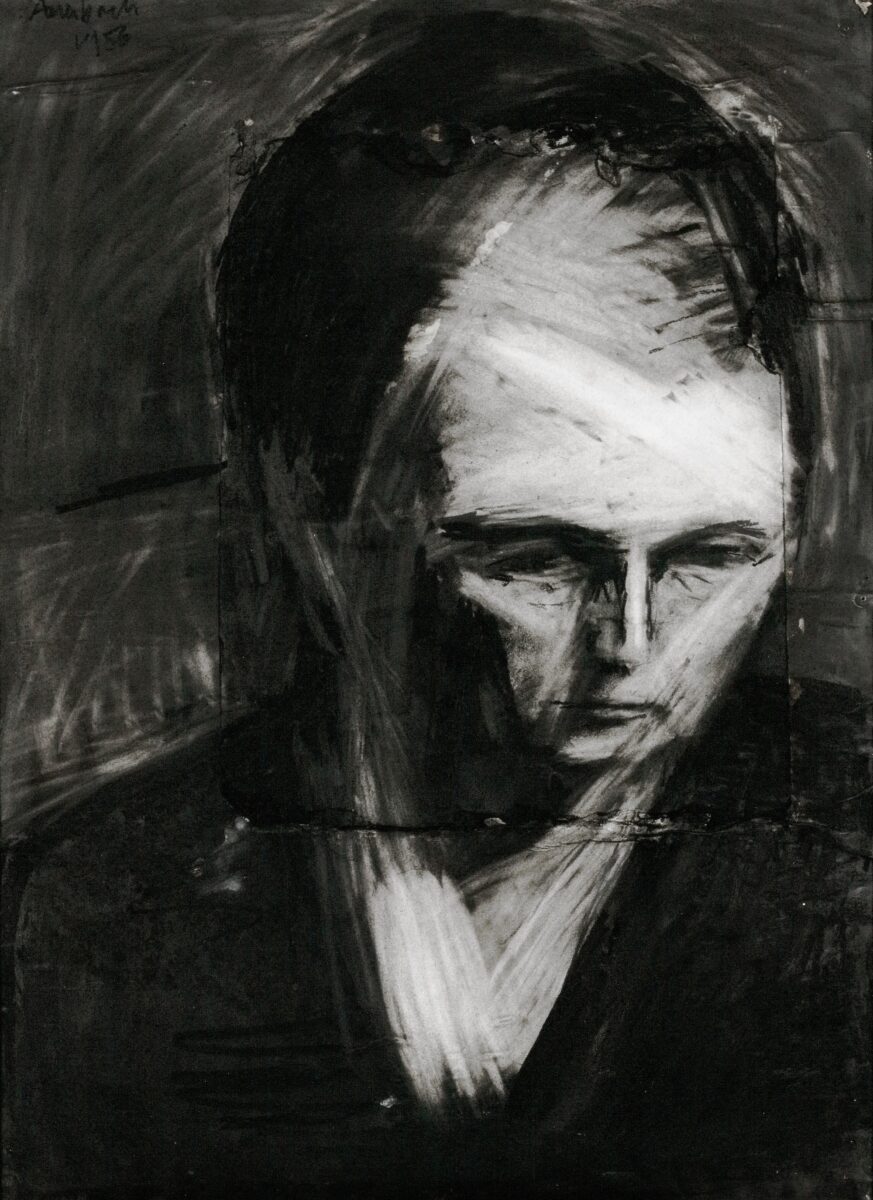

However, the great exception to this tendency can be found when Auerbach depicts himself, in his Self-Portrait from 1958. Here, the artist confronts the viewer, staring unblinkingly into their eyes, and wears his form proudly. Whilst the multiple layers of paper, endless drafting, and expression of his portrait highlight a certain fragility in the work; Auerbach’s scarred and marked representation glimmers as both a confrontation and embrace of circumstance, surmising The Courtauld’s show overall. An artist whose life and work reach through generations, whose charcoal features bear the marks of both, is ready to meet a new audience.

Frank Auerbach. The Charcoal Heads, 9th February – 27th May 2024, The Courtauld