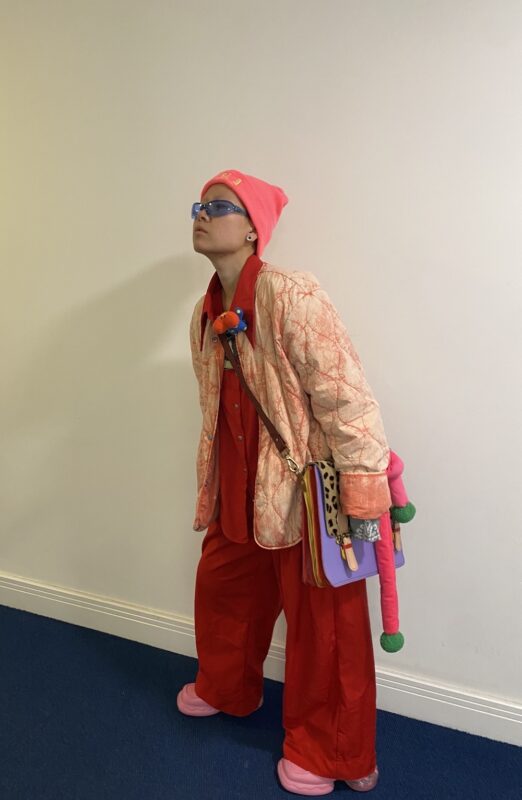

Residing and working in London. Miranda Forrester is a figurative artist with a BA in Fine Art from the University of Brighton.

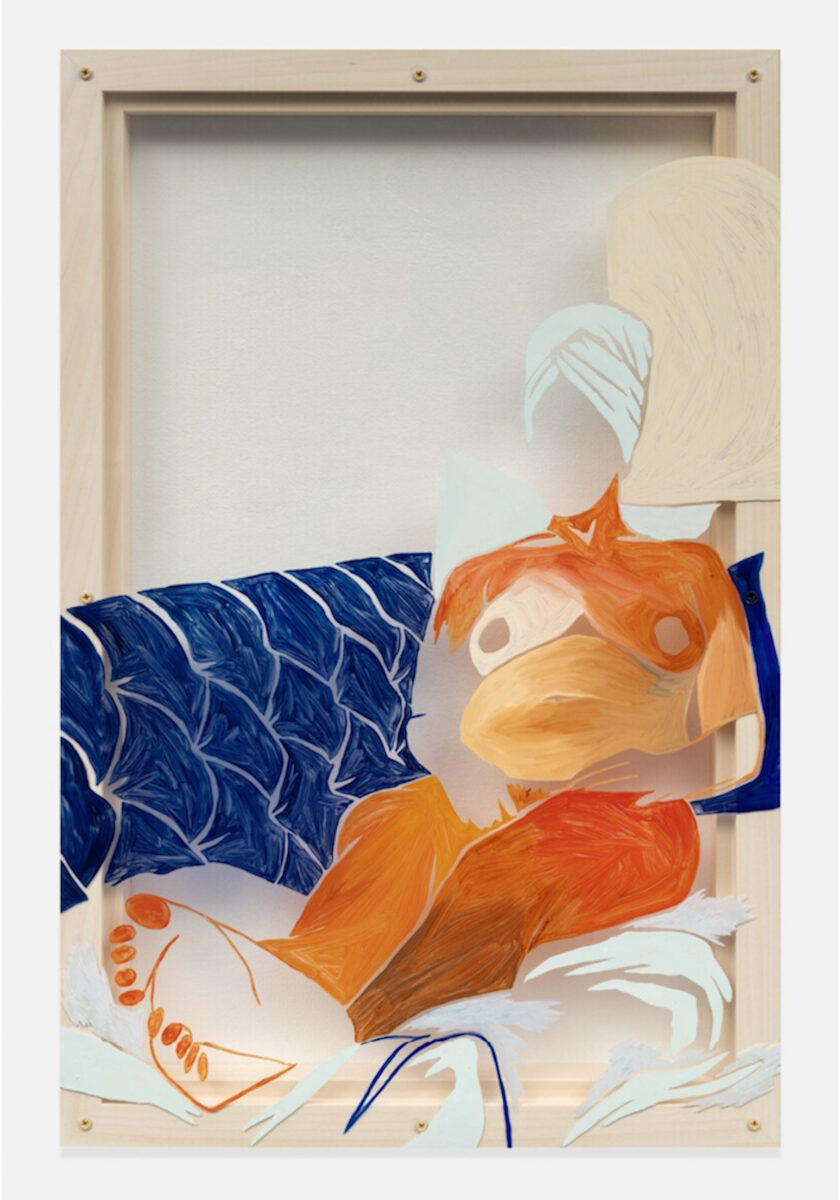

In her recent solo exhibition, Arrival, at Tiwani Contemporary, Miranda Forrester intimately delves into her journey as a non-birthing mother. Throughout the show, we see responses to the uncertainties she encountered as a new mother. By using a vivid and soft approach, Forrester captures the intricate complexities of motherhood and challenges traditional perceptions ingrained in society.

Chard Adio: The first thing that caught my attention in this show was the use of polycarbonate, but before we delve into it. Let’s talk about your use of PVC since it’s been a part of your practice for a long time.

Miranda Forrester: PVC is an interesting material because, during the early days of my practice, I was looking for plastics that could stretch—like canvas. When I first used PVC people were so confused. They would look at the work, and ask me, “How did you do this?” And I would say to them it’s the material’s tensile strength—it’s similar to canvas but translucent, and you don’t have to prime it.

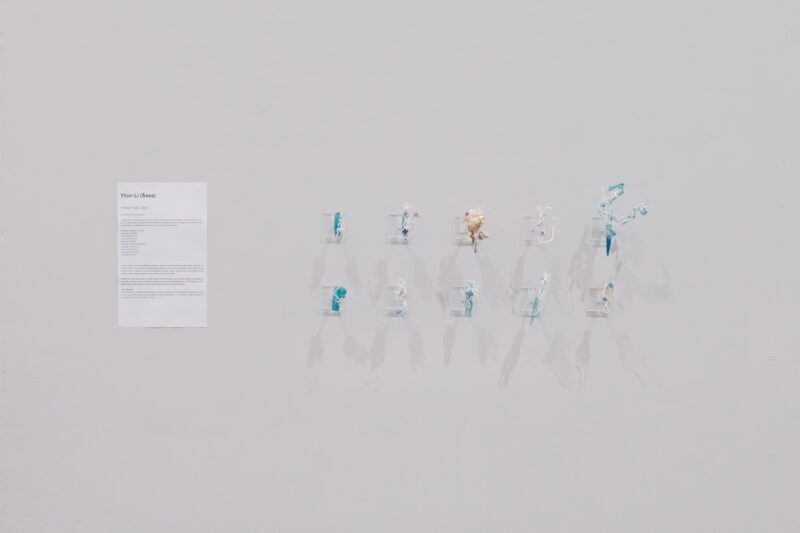

CA: I see! So why the eventual transition to polycarbonate because when I look at your contemporaries, I rarely see other artists use it—it’s such a unique material. Also compared to PVC, it’s transparent.

MF: I’ve continuously explored transparent materials in my practice, and I eventually pursued polycarbonate because I wanted a hard material that worked with bespoke framing. By shifting to bespoke frames, it allowed me to experiment with different types of wood. With polycarbonate being a harder material, there’s instantly this contrast between the composition’s softness and the work’s physicality—the work now has this 3D element to it—you could even say it’s a sculpture. Shadows also appear in the work too, so you immediately see this second image. Also, with polycarbonate being such a reflective material, you can now see a painting within another painting along with yourself which I also like—you as the viewer are part of the work.

CA: Compared to previous exhibitions, how was the process for this show different? How would you describe the build-up to Arrival?

MF: Arrival was the first time I made a large body of work without being interrupted. Because before, I would make work in groups of threes or fours; the work would be sent off, and I would move on to something new. But with this show, it was different—my focus was just on this body of work. In a typical group show, I would just make one large-scale painting, but for Arrival I made so many—I definitely feel more comfortable painting at a large-scale—in previous shows, I would scale up the small-scale paintings. In terms of build-up to the show, I didn’t feel overwhelmed; I felt very calm making the works because I had all these ideas stored up from when I was spending time with my daughter after her birth. So when it was time to return to the studio, I knew what I had to do, and everything just came out organically.

CA: If we look at the work, we are presented with these domestic scenes which are personal and intimate—it beautifully captures family life. Was this intentional?

MF: When it comes to the work I create, it needs to reflect my personal experiences. I wish I could create work about other subjects because I’m often inspired by other things. But I can’t—I don’t know how to do that. Retrospection is vital to the work, and with this show, it was my first-time doing self-portraits. Initially, I didn’t want to take a cliché approach and make paintings of babies. People would often ask me during the lead-up to Arrival, “Is your daughter the focus of this show?” Or, “You’re a mother now, so the baby must be the focus in the art…” There were so many questions surrounding my daughter and the work, and I wanted to fight against this implied ‘trope’. I didn’t want people to look at the work and say, “Here we go again… Another artist turned mother…” So I looked at a personal moment in my life, and coincidently I became a mother at that time, so it was impossible not to incorporate this new chapter of my life into the work. So this idea of exploring motherhood with domestic scenes started with a few paintings for the show, and then suddenly morphed into all the paintings, and it happened in such a natural way. I liked working with the domestic scenes because it involved our family home, and for me a person’s home is their most important place—home is where you feel free—it’s your own sacred space.

CA: Since becoming a mother, what’s the dynamic like being both an artist and a mother?

MF: The dynamic has been interesting; the two have similar energies because your paintings are your babies. But honestly, it’s been a huge privilege to do the two because I’m able to make work and be a mother to my daughter. If you look at the past, artists had to choose between the two, and only a handful did the two—there was so much discourse around this topic. But I think today we’re in a different landscape, and society’s views on the idea are somewhat changing.

CA: It’s an interesting point because one artist I immediately think of who did the two was Sonia Boyce. A contemporary artist who is seen as one of the greatest female artists to come out from the UK has been a mother for years, and back then she was seen as the minority. But you’re right, things are changing, and to be an artist and a mother is seen less as an abstract or new concept.

MF: Exactly! And I think it goes without saying, things have been challenging at times, there has been a lot of trial and error, but it’s natural especially when you have a new-born. When our daughter was born, my partner and I were both off from work—I gradually returned to the studio, part-time and then eventually full-time. So having that flexibility as an artist also adds to that great privilege.

CA: In the piece Do you love me? you address the initial insecurities you faced being a non-birthing mother. How did this piece help you during that period, and what did you think about?

MF: Do you love me? helped process my emotions after my daughter was born. The piece reflects those first six weeks in particular. It was a very intense period; I was extremely sleep deprived, and as a result, my emotions were heightened. One time during a night waking, my daughter was crying and wouldn’t settle with me. She wanted my partner who was breastfeeding. At that moment, I felt a huge sense of inadequacy; I thought I was not the preferred parent. I can laugh about it now since babies have a strong survival instinct—she was hungry and knew her milk wasn’t coming from me. But I think when you are a non-gestational parent, there is initially a sensitivity about bonding and roles, particularly because of the judgement you face externally, and due to the lack of visibility and examples of queer families.

CA: Arrival also touches upon societal prejudices towards queer relationships and families, how do you navigate that intersection of personal storytelling and advocacy in your work, especially on topics that challenge ingrained heteronormativity within society?

MF: Art is my language, it’s how I succinctly communicate my thoughts and personal experiences. Without it, I would struggle to communicate those ideas. So the only way I know how to discuss queer relationships is through the work. Within society, I think there is a huge lack of awareness of queer families. Queer families face so many obstacles, for example, accessing public health services like the NHS. As a mixed Black, queer woman in an interracial relationship who is now a parent, there are so many obstacles I face on a daily basis, and it can be exhausting. So that’s why the work exists, and that’s why you have Arrival; I wanted to challenge people’s notion of what a mother is. I think people are confused about queer families because they can’t comprehend the presence of two mothers in a family; people only see a mother & father in a typical family, and perceive the roles as entirely different from each other—I think a vast majority of heterosexual couples uphold this dynamic. As a society, we unconsciously see this polarity because it’s all we’ve ever known up until modern times. Queer families don’t have any rule books or blueprints, so the work is there to document such relationships. As someone who has a child with another woman, we both assume the role of mother because we are still women. The way I feel about my daughter isn’t different from my partner; the parental roles within my family doesn’t need to adhere to this polar model we’ve traditionally seen.

CA: This is a great point because it leads to my next question. Within Arrival, we see some references to other artists who also explore queer relationships. In Two mothers, one scar we see Sola Olulode’s work, and in Babymoon you pay tribute to Catherine Opie. Why was it important to include these other artists?

MF: I’ve always been invested in paying homage to artists who have paved the way for individuals like me. Representation in the arts is so important, and I looked for that representation during this show. I had to include Catherine Opie, because her work and how it discusses queer families is still poignant to this day. Self-Portrait/Cutting is the piece I referenced in Babymoon, when it was shown 30 years ago, there was so much controversy surrounding the piece. What’s also intriguing but crazy is the conversations that were happening back then about queer families are still happening now. With Sola, I wanted to showcase a black perspective on queer relationships since that conversation barely exists within the canon of art history. So referencing Sola also made sense: she’s my friend, my peer, and there’s synergies in our work.

CA: Nature is also something we need to discuss because throughout your work it has made multiple appearances, from the earliest paintings to now. From what I see, you don’t just incorporate nature; you incorporate its essence because the colour tones in the work are warm and earthy.

MF: Nature is also an important aspect of the work because it symbolises growth, and in the case of this show, I see nature as something that represents a child’s development. Plants grow, and so do children; plants adapt to their surroundings, and so do children. In an enchanting way, the two are dependent on you for their survival. But beyond that comparison, I also see similarities between nature and life. In life you carve out your own space to co-exist with other people—like a plant—you spread out your roots and form these connections with other people you meet.

CA: Lastly, within this show, we have the furniture piece, Conversation Piece. This was a collaboration between you and furniture designer & maker, Mandie Beuzeval. How did this collaboration come about?

MF: Mandie is a friend and the only woman I know who works in woodwork and furniture design both of which are very male-dominated industries. So when I was coming up with ideas for the show, I just saw an opportunity to collaborate with her. I wanted to highlight her work since it uses sustainable materials. I designed the fabric, and Mandie designed and produced the chair. I think the furniture is a great addition to the show because it creates a sense of warmth and homeliness, people can sit on it and interact with it—it’s a physical representation of what you see in the paintings. And even with the mural you see in the gallery, it’s a similar thought process—an additional feature that makes the show a bit more dynamic and takes my visual language out of the frame into something you can engage with.