Reading the exhibition text at Barbican’s RE/SISTERS, A Lens on Gender and Ecology, one could get the impression that environmentalism and feminism were cut from the same collateral cloth; two peas in the same subaltern pod that, because they are both marginalised, benefit from being surveilled unilaterally. The text goes on to cite the oppression of Black, trans, and Indigenous communities, and parallels with ongoing environmental degradation. For an institution to scrutinise any kind of oppressed people is a slippery slope to say the least, but the text makes the important distinction that this is a survey of systems, not a comparison of experiences, and most of all it is a female perspective.

The most resounding connection made in the ensuing wall texts, and the exhibition itself, is the relationship between ecologies and ethnographies to the greater economy—that being the inescapability of exploitation from labour. The element of labour; more precisely the flat-out prostitution of natural resources (what the exhibition describes as extractivism) highlights junctures between the erasure of fertile lands and expectations of the female body.

While there are undeniable intersections between the atrocities endured by women, the global majority, and the actual planet itself—raped and repressed by the same power structures and pioneering social order—the neat text succinctly brushes over the complex stratification of ecofeminist progress and the selective partition of various bodies, be they corporeal or terrestrial. What is not mentioned are the ways in which making headway in one of these sectors can often result in a regression for the other.

The most basic way I can paint this visual is with a quantitive aptitude equation featuring a cat trapped at the bottom of a well. As she climbs out, she slides down one rut for every two she gains. One misplaced foot causes the other three to lose traction. Much in the way that the cat continually writhes, recedes, and deteriorates as she advances, the exhalation of oppressed social groups and the environment can be similarly coupled with vestigial setbacks, sometimes exacerbated by one another.

The text asserts how notions of potency, pregnancy, and productivity continue to hold the propagation of social and environmental justice to unrealistic standards, attributing this to a colonial-capitalist agenda. An increasingly virile platform to observe this tension between the planet and the oppressed majority is the ruthless landscape of social media and its role within the sphere of reproductive labour.

One misstep by the cat and she may plunge deeper than where she started. For example, most of us are familiar with the iconic American businesswoman and television personality Martha Stewart. Having built her empire based on capitalising off of reproductive labour, her $400 million business ascribes to radical feminist movements, either directly or indirectly.

Earlier this year on a Swan Hellenic cruise from Iceland to Greenland, Stewart took to Instagram to flaunt a tiny iceberg that she and her crew had “captured” from the glacial water for the intended use of chilling their cocktails. While the casual cropping of indiscriminate bits of floating, severed iceberg is common practice on these kinds of arctic cruises, and the government allows a certain quantity of ice to be collected for tasting, the post incited outrage across social media for its alleged insensitivity to the climate crisis.

The reaction to Stewart’s ice harvest is just a small example of how cross-pollination between the movements can bring about unintended associations. Though Stewart did not get outright cancelled, she certainly ruffled some feathers, and managed to piss off environmentalists as well as proletariats in one fell swoop. But how much did it have to do with ice and how much to do with her persona?

As a domestic accessory, ice has become a status symbol, with entire social media channels centred on designer ice culture. “Icetok”—a TikTok rabbit hole dedicated to ice—depicts couture ice as a mega-trend, complete with different shapes, colours, additives, etc, in which case Stewart was just flexing her ice swag. Most people weren’t actually upset that she took the ice; they were upset because she glorified an unattainable standard that is inaccessible to most people, particularly women, who don’t have the luxury of capitalising off their undervalued and underremunerated reproductive labour.

The irony of ice as both a birthright and a proliferation of global warming is not lost on the international community. One top comment noted that the broken iceberg was already melting, in which case waiting for it to become water and then refreezing it would in fact be more harmful. Another commenter joked that “if you can’t find fresh icebergs for your cocktails, store-bought is fine,” which speaks more to Stewart’s status as a celebrity than as a coloniser of ice.

The thing is, the melting of ice is not only a repercussion of ecological degradation but an erasure of habitat for hundreds of thousands of people living in frozen geographies, especially indigenous people. In the exhibition, London-based artist and researcher Susan Schuppli’s film Cold Rights probes the politics of ice and its profound consequences, not only on global warming in general but for regional communities and national sovereignties.

The fourteen-minute single-channel HD video is exhibited on a moderately sized screen with headphones, giving the piece an intimate feeling of academic reverence. It provides a comprehensive narrative of a failed petition submitted by Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier on behalf of herself and 62 Inuit people in 2005. The petition, which advocated for the right of ice to remain frozen, or as Schuppli describes it, the right to be cold, was dismissed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

The film highlights with great detail and precision how corrupt legal systems and governments are directly responsible for gross negligence, motivated by access to oil and gas reserves. Meanwhile, the visuals weave together stunning air, water, and ground footage of frozen vistas and the changing material states of ice; something that is simultaneously beautiful and tragic. Again the notion of labour arises in the story of the Canadian government forcefully relocating seventeen Inuit communities in the 1950s, where not only were their traditional ways of life rendered impossible, but they were forced into working as an underpaid task force for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

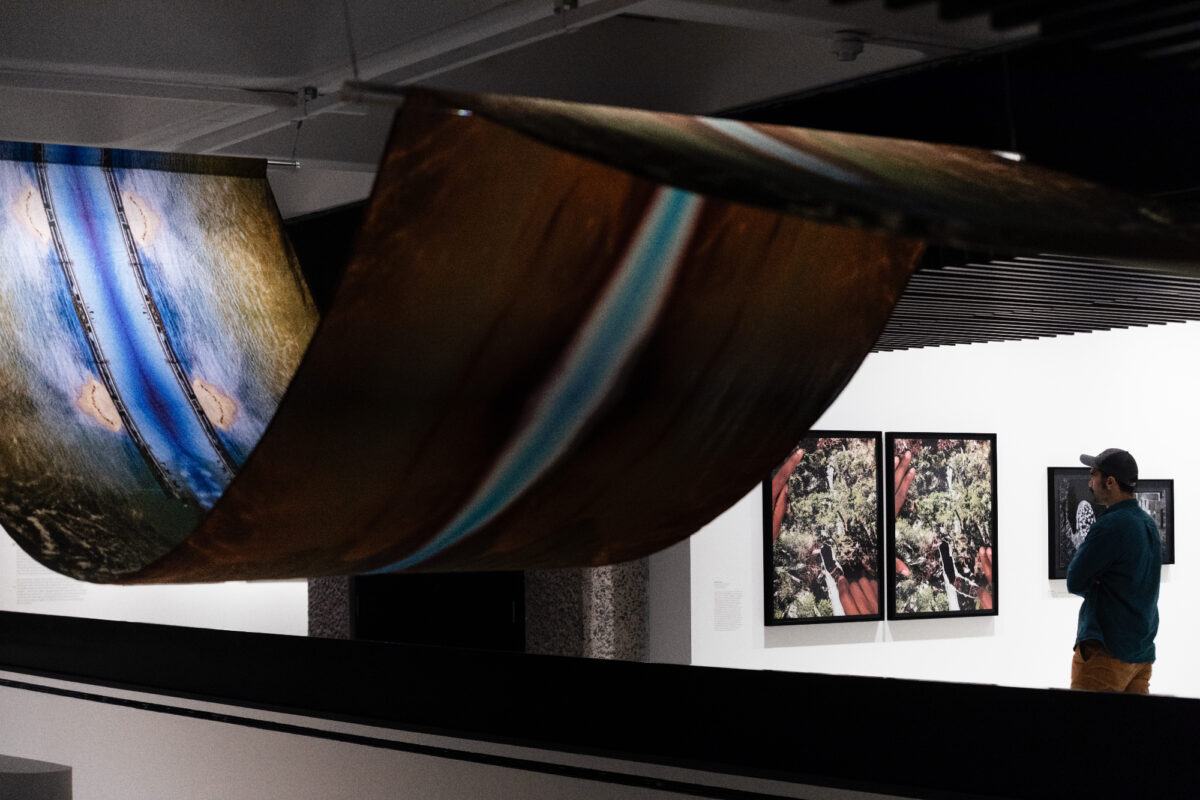

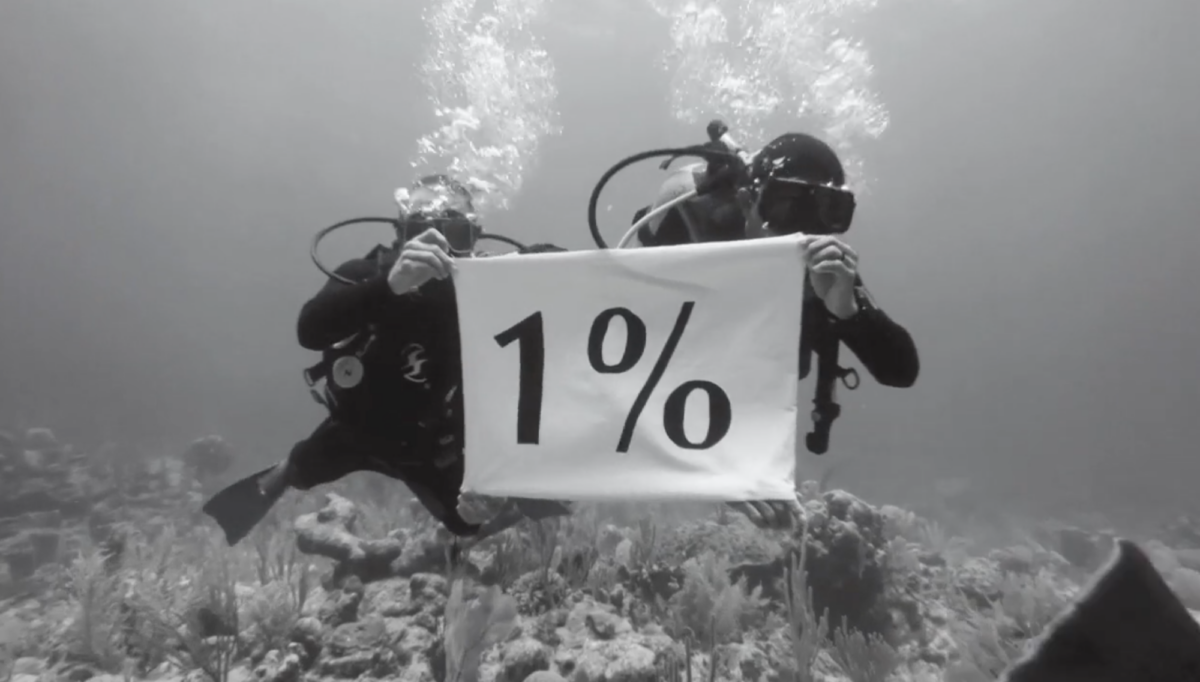

Delivering on its promise to unveil the colonisation of the deep seas, the installation includes a powerful projected film from the ocean floor titled A Draught of the Blue, 2013, by Mexican artist and activist Minerva Cuevas, who is known for her socially engaged, site-specific interventions. Though not completely silent, the muffled and abstracted gurgles give the single channel HD video an eery sense of despair. The ocean floor feels lonely and haunted. Less than ten minutes long, the video loops in a seamless underwater scape of silent protest.

Filmed off the Yucatán Peninsula, we see two rebel divers descend into the deteriorating Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, banners in hand. They are there to give a voice to those whose voices cannot be heard, including marine animals and the reef itself. The banners depict the words “IN TROUBLE,” “1%,” to reference wealth inequality, and “omnia suit communia,” which translates to all things are to be held in common. The sallowed palette is almost entirely grey, short of a handful of frames. When colour is present, the languid and slightly anaemic shade of blue feels like a pillaged ocean whose life force has been ransacked by greedy pirates.

Rarely exhibited video footage of Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ maintenance art practice, including Touch Sanitation, draws parallels to the devaluation of labour, accompanied by photo documentation of the artist shaking the hands of New York City’s 8,500 waste disposal workers from 1977 to 1984. Ukeles is seen hanging out with the sanitation worker crews, commending their dedication, and resourcefulness, and lamenting the lack of acknowledgement for what would now be referred to as “essential work.” As with reproductive labour, these workers are undervalued, underappreciated, and unseen.

Her intentions seem genuine enough, but Ukeles sticks out like a soar thumb. Her project was not meant to be didactic, but l wonder how much consent the workers actually gave, and how performative it was of her to play a role, like a touring politician in her in crisp, matching, salmon-coloured outfits against the staunch ubiquity of the workers in their actual uniforms. Yes, women are marginalised, but does that mean that every last one of them gets to compare themselves with the disenfranchised workforce, often immigrants, who have to do the jobs that nobody else will? After all, isn’t being able to afford to spend seven years pretending to be a city worker the pinnacle of privilege?

Funnily enough, Ukeles’ piece is exhibited for the second time at the Barbican adjacent to Agnes Denes’ Wheatfield pictures, in which Denes planted a two-acre wheat field in an empty landfill next to the World Trade Centre in the summer of 1984. Works from the same two series from Ukeles and Denes were exhibited in Barbican’s group show Radical Nature in 2009, which was subtitled Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet.

Perhaps they are just the go-to for Barbican exhibits about ecological art? One wonders whether the legacy of these two artists has become tokenised as well as which art historical boxes must be ticked for a survey to fit into the ecological canon sufficiently. Or, as my friend put it, “It means they can park feminism and ecocide for another five years whilst the Barbican returns to the white male able-bodied hegemonic status quo with blessings from the City of the London inner sanctum.”

In any case, the survey treads on thin ice and does it with a degree of success. What it perhaps misses in its quest to portray the interconnectedness of oppression is the tension between the advancement of social and environmental justice, not to mention the slightly trite allusion of woman as planet, or mother earth. This anxiety presents its own sometimes self-sabotaging dynamic which does not seem to be addressed despite its very real and unspoken urgency. What the exhibition calls comradeship I might call friendship. Or, at the very least, they’re frenemies.

RE/SISTERS, A Lens on Gender and Ecology —14th Jan 2024, Barbican Art Gallery