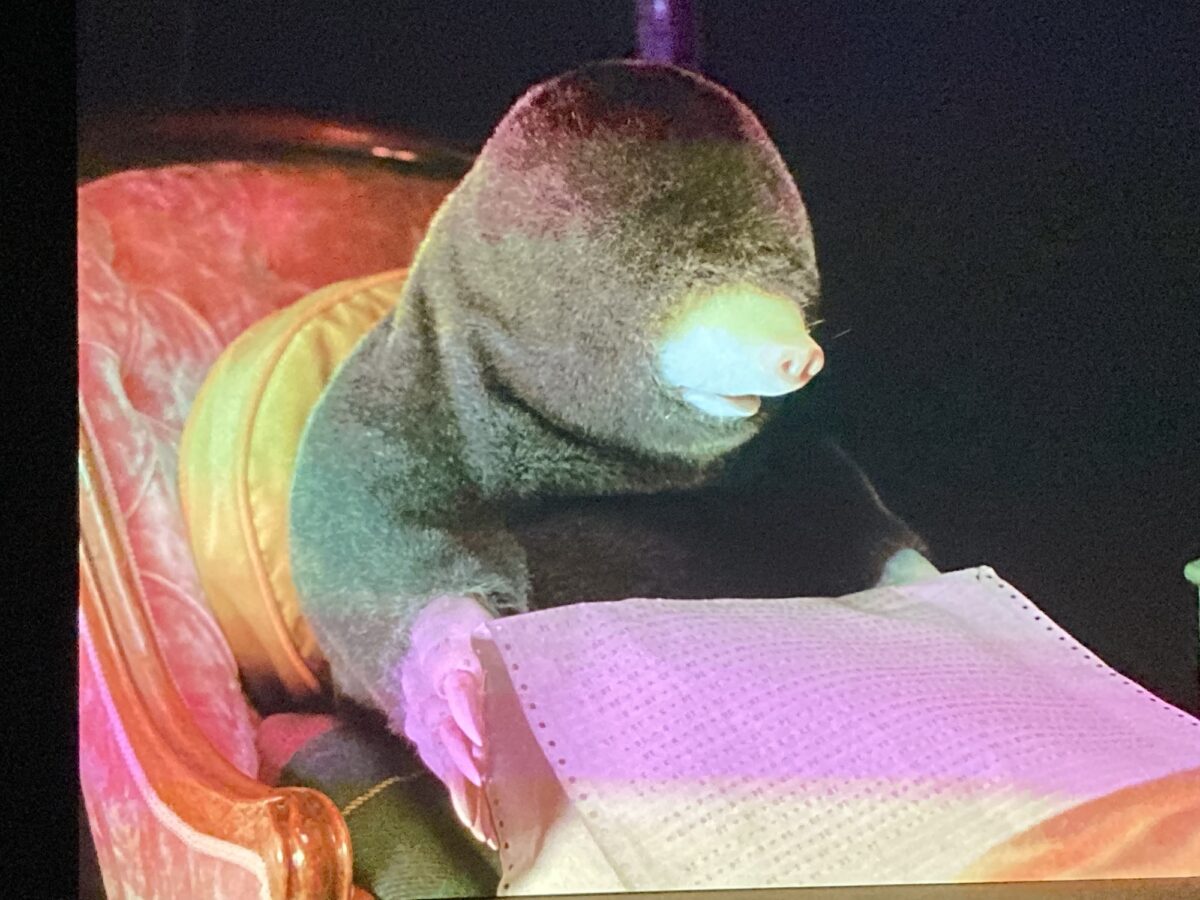

Four moles shelter in a fully furnished hollow. Two ailing children sleep, snug in their bed. They whistle and snore lightly while their parents huddle in the next room. A slow fire crackles in the corner as they converse, painstakingly reciting numbers back and forth from an interminable stack of printer paper that they clutch with their grubby mole talons.

What, or rather why the moles are counting is a good question, and probably one with no answer. When asked about the incentive for casting moles in his films, Italian artist Diego Marcon describes the animal as a character who chose him, and not the other way around. He says that while making a previous film, The Parents’ Room, the idea of a counting mole arose.

One does not need to speak a word of Italian to understand what the moles are saying; what’s more, the numbers can sometimes get away from them, and the exasperated intonations and careful calculations speak volumes beyond the words. The repetitiveness of the dialogue and the peculiarity of their behaviour is simultaneously comprehensive and blissfully bizarre.

Marcon is known for his structuralist cinematic approach, which uses repeating structural elements such as hidden codes, prop placement, and camera angles to convey meaning and support underlying narratives to the audience. These kinds of structural cues become a language in themselves, and render the actual spoken language – in this case a ceaseless string of numbers – less literally significant.

Every so often the moles reach a kind of numerical impasse; a mathematical disagreement, at which point they struggle over a sum. Each parent becomes exceedingly exasperated until finally, they start the count again from the beginning. It is because of this tiresome restart, the tediousness of the task itself, and the illness of the children that critic Travis Diehl notes the suffering shared by Marcon’s characters, and most notably his moles.

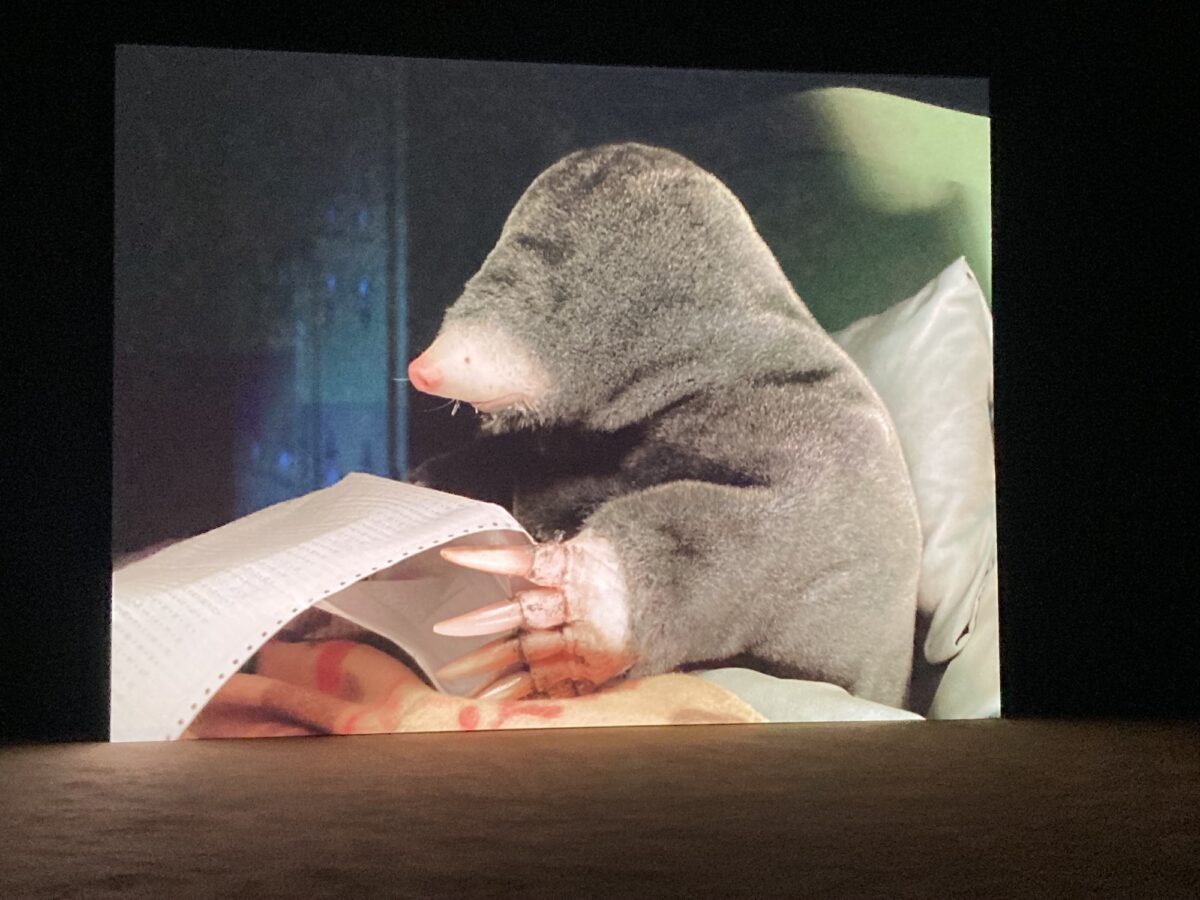

With each new round, I keep waiting for something to happen. Unlike me, the moles seem to be graciously patient in the futile endeavour, and it slowly sets in that this is perhaps all that will happen. Because the film loops so seamlessly, it is impossible to know how many times they count, and even less apparent when the 29-minute film itself starts again.

There are small indications of the passage of time that continually challenge my assessment of any beginning, middle, or end. A hooting owl, a cuckoo clock, or sounds from a dripping tap. The children cough, and something, somewhere off-camera, comes crashing down. These small distractions and atmospheric acoustics activate the imagination, enlivening this kind of suspended reality where moles do human things.

There is something universally appealing and gloriously impractical about anthropomorphism. As another trope in filmmaking and ethnological storytelling, the fact that animals are given voices, clothing, or furniture is not only a narrative tool but an invisible and widely appropriated convention.

Like in his previous show, Monelle, the humour in Marcon’s work operates out of a place of paradox. Something iconic is equally generic. Though the moles are reading, they have no eyes. Much in the way that numerous iconic cartoon animals don’t wear trousers, their partial humanness doesn’t have to make sense. It only has to stretch the story enough to make you invested, and the viewer will self-rationalise the rest.

The progression of the space and sense of delayed gratification reflect Marcon’s characteristically austere expressions of psychological states through quiet, understated narratives and cinematic archetypes. In fact, the architecture at Sadie Coles HQ Kingly Street lends itself to the curatorial version of prolonged expectation. Located towards the end of a bustling pedestrian ally in Soho, the nondescript entrance would be easily overlooked and the reception gives away very little. Aside from a few books and a desk, nothing much happens here either. The staircase winds up to the second floor, opening onto yet another vacant space, both hospitable yet unoccupied. One knows there is something to be seen, eventually, after a series of twists and turns, ascensions and arrivals.

Though the film is structurally consistent with Marcon’s other work, the background information remains sparse compared to the extensive and thorough literature behind previous exhibitions, such as a lengthy exhibition text and corresponding video interview with curator Alessandro Rabottini in tandem with the March exhibition at Davies Street. Instead of any kind of explicit description, the exhibition text provides a numerical reference; 16 + 21 + 12 + 9 + 19 + 3 + 15 + 3 + 1 + 19 + 1 + 5 + 14 + 15 + 14 + 5 + 19 + 3 + 15 + 13 + 1 + 9 + 21 + 19 + 3 + 9 + 18 + 5 + 4 + 9 + 3 + 1 + 19 + 1 + 19 + 1 + 9 + 6 + 9 + 14 + 9 + 18 + 5 + 16 + 15 + 9 + 14 + 5 + 9 + 7 + 21 + 1 + 9, and nothing more.

Diego Marcon Dolle, 2nd November – 16th December 2023, Sadie Coles HQ, Kingly Street

The debut screening in the UK marks Marcon’s second Sadie Coles HQ exhibition this year and coincides with Marcon’s first institutional exhibition in Switzerland, entitled Have You Checked the Children, at Kunsthalle Basel (on view until 21st January 2024). Dolle will also be on view from 8th November to 22nd December at Galerie Buchholz in Berlin.