Berlin-based breakthrough abstract artist Xiyao Wang uses her knowledge of Asian and Western traditions to find freedom in working on large-scale, immersive paintings. Using a combination of acrylic, oil, chalk, oil sticks, and graphite, Xiyao Wang is celebrated for her distinctive use of colour, volume and texture evoking movements and space.

Her recent sell-out booth at Frieze London with MASSIMODECARLO was inspired by rituals and minimalist thinking. Xiyao Wang speaks with Jessica Wan about how returning to the essential can be a response to our increasingly complex world.

Jessica Wan: Your recent paintings convey a dynamic and powerful state of fluidity with reduced expressive lines and colours. What is the intention behind this new series of works?

The title of these five works is En L’air, which literally translates to “in the air” in English. It comes from a term in ballet describing positions for doing pointers in the air. I love this concept because when you are in the air, you feel total freedom; you are weightless and boundless, you can do everything, you are in the middle of something, but you are not on top of it, and you are not on the ground. I envision this state of endless possibilities for every single change.

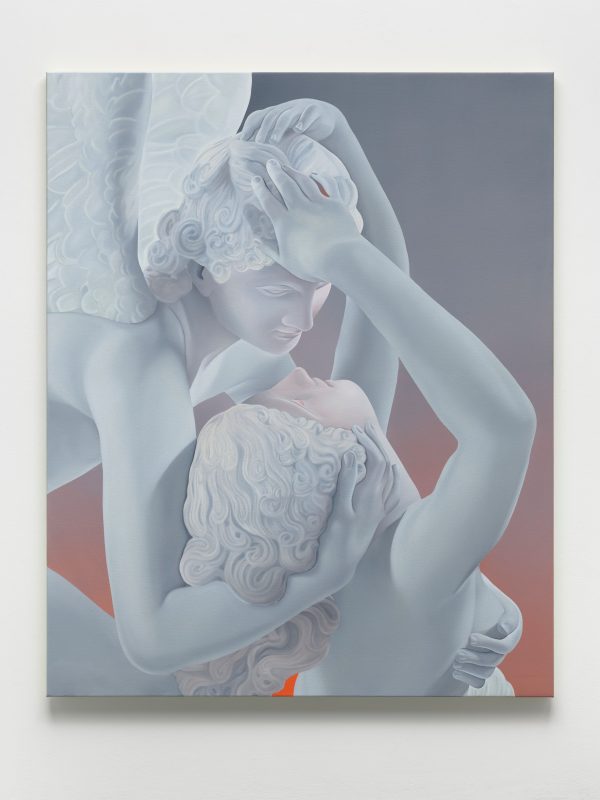

The blue and orange combination refers to the depiction of celestial flying fairies in the ancient Buddha’s frescoes from Mogao Caves, a historic site on the Silk Road in China. In this context, ‘in the air’ is an act of transiting or transversing into outer space or another dimension.

JW: Painting can require a lot of physical energy and concentration. I know that you engage in many bodily practices, such as kickboxing, ballet and yoga. What are you getting excited about at the moment?

I learned to engage my mind through different body movements. Now I do ballet mostly. Practicing ballet is like trying to fly; in martial arts, I’m just preparing for one moment for extension with very controlled strength. In kickboxing, I have to push out all the energy for one punch, a moment like an explosion. Yoga is like a river, and your energy flows with it. It’s not about one punch or one flight. It is a continuous engagement in a contemplative way.

JW: Your gestural brushstrokes evoke the feeling of a dream-like landscape in search of new encounters. Would you say that you are reaching some sort of subconscious state while trying to capture that moment of ‘flow’? Do you sometimes avoid thinking about the movement that you inhabit?

Actually, I also use my painting or ballet or playing instrument as a form of meditation to be present or transit to another world. When at work, I am fully concentrated in the very moment. This generates a space where only me and the painting exist. It is the state of being connected to the world at large. It’s a very special moment. At this moment, I’m totally concentrated, and I transfer myself through every movement into the lines and each part of the painting.

I let my movements freely flow into the painting, but there are some movements I have to counter. For example, the movements of dancing and early training in sketching with charcoal sometimes come automatically into my painting. However, the habitual movements of painting are something I have to work against because I am longing for challenges and new possibilities.

JW: From what I understand, ballet is a highly controlled choreography that requires the body to follow a rigorous pattern to perform the desired form. How do you balance precision and improvisation in your work?

To me, improvisation is about embracing the surprises and the possibilities. I always start painting with some ideas, but the work will always differ from what I thought. This is when I have to allow emergent rhythms and elements in my practice because I am collaborating with my body and mind.

Precision and improvisation are connected while creating my art. Unlike ballet, I need to be open-minded and able to express my thoughts, but precision is a necessary part of my painting process. I need to be aware of the boundaries of the canvas; I need to control the painting’s structure and forms, the art material and the colour combinations, and the different strengths and directions of the lines. At the same time, I need to be open to new possibilities and spontaneous developments.

JW: It seems that rituals and habits are key in our conversations. Throughout human history, we engage with ritualistic practices for various reasons, be it ceremonial and spiritual. In a contemporary society where our attention is constantly being consumed, what is your hack to get headspace or keep track of your thoughts? How do you reach a flow state of creativity?

I am highly protective of my creative and personal space. The first lesson for me in COVID was learning how to say no. People become understanding of refusals, and I realised it’s not so bad if you say no because nothing changed. I’m now working with four galleries on multiple projects, so my daily life is always fully booked with meetings and different appointments. Because I can’t paint right after meetings I need time to reset my mind. I set up the beginning of every week to do office things. There are always three or four days in a week when I do not meet anyone, take no appointments, and just be there for myself.

In this time with myself, I do things that free my mind, like taking my concentration inward through the tea ceremony. This helps me to observe my thoughts. The whole progress of creation is not only about the painting itself but the preparation, mentally and bodily, to get into this ‘flow’ state. I get most of my inspiration in my studio and not from traveling. The more time I spend there, the more ideas come to mind. Of course, I am also learning a lot through great exhibitions or being in nature, which is very spiritual. It’s essential to keep the ritual of doing what you love.

JW: Could you tell me a bit more about your experiences in nature? How does it make you feel connected to the inner self?

I don’t always have the opportunity to be in the wild, but I feel more connected to the universe every time I am in nature. That’s probably why I love to swim in the lake instead of the swimming pool. I think a tree has its own life and story when I see it. Recently, I started taking lessons on the Guqin, a traditional Chinese plucked seven-string instrument with thousands of years of history. Sometimes, it is played by Taoists as a method of meditation but not for the audience. They practice it in nature, sometimes behind a waterfall or by a Lake. Guqin has a distinct ambivalence inspired by the sounds of water, wind and animals as it is used to communicate with nature.

When I practice Guqin, the world around me becomes quiet and calm, and I feel the gesture of my finger as if they are reaching out to another universe. My favourite routine is playing this instrument after breakfast to start my day. During the day, I do a tea ceremony. In the afternoon, I begin to paint. I don’t paint in the morning because mornings are for reflection and planning.

JW: Looking ahead, what are you working on at the moment?

I am working on a new series of works for my upcoming solo shows, one at Song Art Museum and Tang Contemporary Art Beijing, in December, and one at Perrotin New York, in January 2024. There will be works that have never been shown anywhere before. It will be something new and different. This practice fits my current state of being reductive and adaptive in progress, continuing to capture the void and construct the atmosphere of boundlessness.

Keep up to date with Xiyao Wang @xiyaowangart