It felt harrow. The weight of white-washed walls rising. Here, that is there, space was made thick, or disturbingly claustrophobic, through an empty, automated, ambience. Here, that is there, I stood within bareness, in anticipation, awaiting some kind of revelation. Not much arrived, but still, that nothingness resounds.

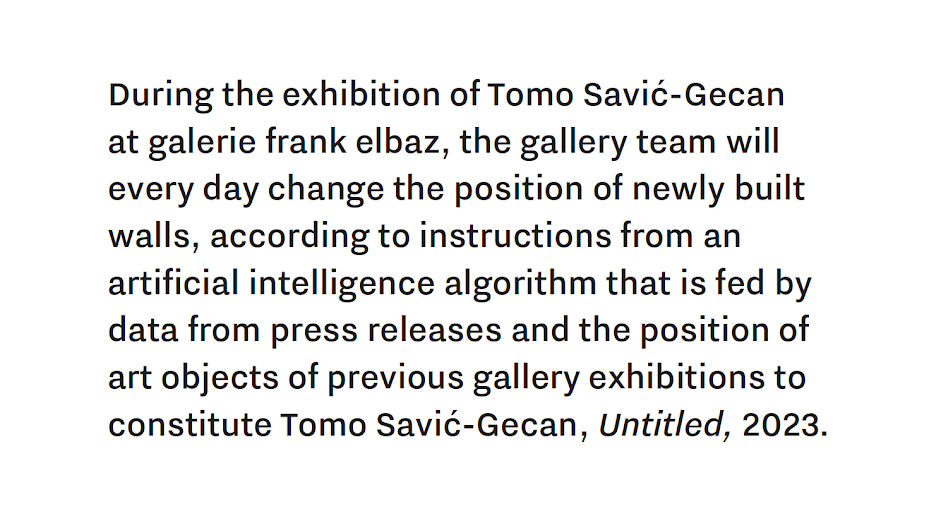

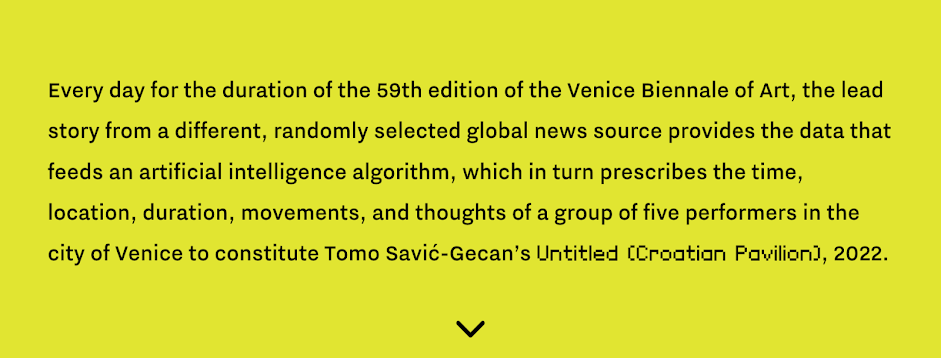

Tomo Savic-Gecan’s solo exhibition Untitled, 2023 (galerie frank elbaz, September 2nd – October 7th, 2023) was bare. A void, with minimal content—a vertical screen, three white walls and tools for a daily performance—the artwork shown inscribes itself within the series of AI-based, semi-performative artworks Savic-Gecan has made following his participation in the 59th Venice Biennale of Art—where he represented Croatia with a piece titled Untitled (Croatian Pavilion), 2022. As with that disparate performance-cum-pavilion, this new work follows a simple premise—a proposition or description, an artist agreement, instruction or score to be enacted. As the work’s foundation (dare I say it’s only ‘tangible’ existence), in the gallery, this premise is visible—typed in black sans-serif and displayed beaming out from the bare space of an otherwise white screen—it reads,

During the exhibition of Tomo Savic-Gecan at galerie frank elbaz, the gallery team will every day change the position of newly built walls, according to instructions from an artificial intelligence algorithm that is fed by data from press releases and the position of art objects of previous gallery exhibitions to constitute Tomo Savi?-Gecan Untitled, 2023.

And so I stood, at 3:55pm, between these monumental walls, unmoored and in suspense, surrounded by AI outcomes, just plain-looking, waiting.

For context, Savic-Gecan’s artworks sit restively between the ephemerality of high-conceptualism, where ideas are the formal currency, and postmodernist approaches to artistic materials, where porous layers of meaning unfix objective knowings. In Untitled (Croatian Pavilion), 2022, for example, Savi?-Gecan drew upon research into how individuals physically manoeuvre and interact within exhibition spaces to compile a data set of minimal choreographic steps. Over the course of the Venice Biennale, these steps were performed daily by a group of non-descript participants across the Biennale’s constituting pavilions. Rather than a predictable or repetitive event—a wholly consumable spectacle—the exact locations, times and even the precise choreography of this itinerant pavilion-performance were determined by an artificial intelligence algorithm, fed each morning by the ‘lead story from a different, randomly selected global news source’, to quote the written premise for that work in the series. In blurring the boundaries between what constitutes the architecture of a national pavilion and the ways bodies physically come to know of the world, be this through the lens of the museum or media, Untitled (Croatian Pavilion) positioned itself as an anomalous gesture, both conceptual and material. Personally, in wobbling this compartmental line, Untitled (Croatian Pavilion) demonstrates how idea and form are inseparable, and most importantly, how both innately constitute an ongoing existence—here, the temporal being of an artwork but this thinking could easily be applied, in a metaphorical way, to the interdependencies that sit central to human existence.

As with Untitled (Croatian Pavilion), and indeed with all of Savic-Gecan’s artworks, Untitled, 2023 resists description; any summary, record or attempt at categorical elucidation is ultimately a futile act, one that directly contradicts the form and restive thinking prompted throughout Savic-Gecan’s practice. As a writer, this knowledge troubles a normative way of doing things… so rather than stating ‘what’ Untitled, 2023 is, prising this spatial activation as an object set in the world, here I want to talk about ‘how’ Untitled, 2023 is; that is, how the artwork came into being, how I experienced this on October 7th 2023, and how the nothingness of my encounter led to some affect thinking.

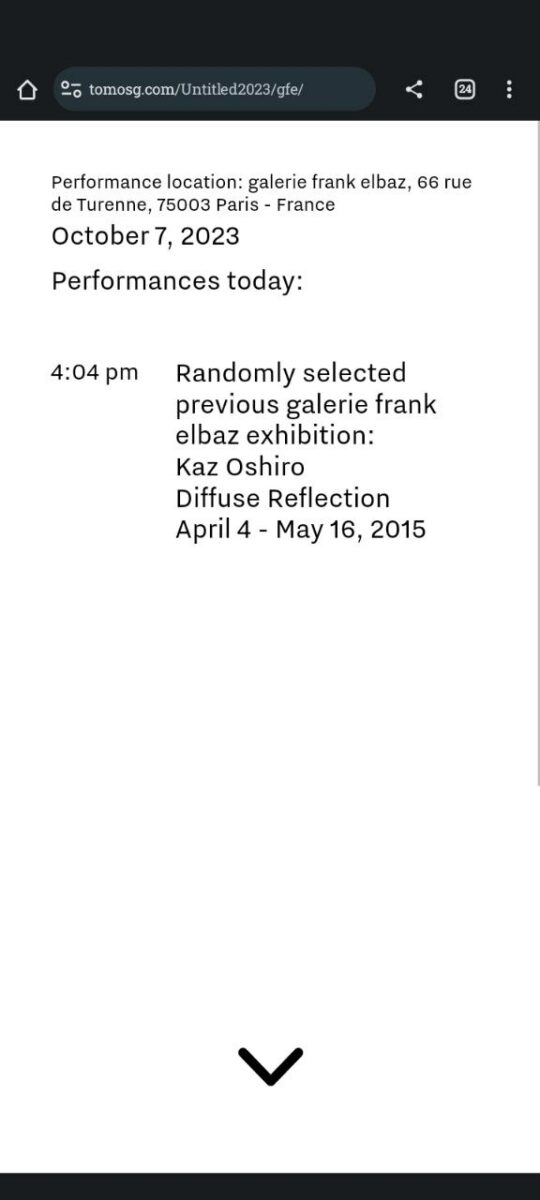

As indicated in the premise above, the data directing the performance of Untitled, 2023 is rooted in the galerie frank elbaz’s exhibition archive. Here, press releases and curatorial plans from over 70 exhibitions held at the gallery since 2012 were fed into an artificial intelligence algorithm, becoming the raw data set that, once analysed by a ChatGPT-based system, provided the gallery’s staff with the parameters for each day’s performative activation—where the newly built white walls needed to be moved to within the empty gallery space and at what time. Unlike previous works in his AI-based series, in this piece, Savi?-Gecan only uses one data source to return these daily instructions (in Savic-Gecan’s pavilion, his data set was cross-read daily by a randomly selected media source). This focus on the context of galerie frank elbaz—the gallery site and its exhibition history—gives Untitled, 2023 a sense of site-specificity. Indeed, to me, this specific situatedness roots Untitled, 2023 in an art historical lineage of artists twisting the common sense sanctity of the modernist white cube—the hidden spatial neutrality which artworks are meant to shine out from, untampered by external life—into a porous medium that speaks subtlety beyond itself. As a slight aside, it is interesting to consider the wider city of Paris in this art historic context. As early as the 1950s artists such as Yves Klein were co-opting the formal space of the white cube to create radical exhibitions which challenged the modernist trajectory of art, its forms and functions; indeed exhibitions which, departing from the radical philosophies of figures such as John Cage, challenged modernist ideologies of life segmented and compartmentalised.

There is something unsettling about entering a seemingly barren space—perhaps one reason why Klein titled his empty exhibition of 1958 at Galerie Iris Clert LeVide [The Void], with its connotations of invalidity and vexatiousness. Personally, I find being exposed to white nothingness arouses a similar effect to being enclosed in a pitch-black room: a heightening of attention, a growing sense of claustrophobia, unease. Entering into galerie frank elbaz, this feeling was palpable. Indeed, surrounded by Savic-Gecan’s new walls, these sly senses pulled me into the emptiness displayed. And, as I slipped into this disquiet, the ambient details abounding in this sanctified space—from the endless blare of the gallery’s strip lighting to the footsteps and hushed whispers of other viewers—became ever louder presence reverberating in my mind.

As the moment of performance arrived, 4:04pm, two nonchalant gallery staff walked softly into the main exhibition space. Meticulously, they set about their work; “trois deux un”, armed with cranks and widgets, with cuboid arms of industrial-looking steel, with wheels, a laser pointer, and a handy jar of Prosain’s Risotto d’Automne filled with screws and the sound of tingles. It was an elegant manoeuvre, an opera writ in architecture; with shuffles and whispers, with taps that became thuds, and slight paper turning; “parfait”. Labouring with a careful cadence, click by click, here the pair demonstrated a level of physical and mental attention needed to install a monumental artwork. As they returned to their daily gallery duties, my attention was brought back to the ambience of my surroundings. What has changed here, really? The gallery’s lights are still beaming down, filling this shadowless space with an unflinching glow, other viewers are still whispering, their footsteps dust sounding. Yet I feel newly present, as my disquiet returns.

Post performance, this active anti-climax lingers in my mind, like a souvenir; as something wholly subjective and indicative of a time, place or moment had. Indeed as something through which I can make out a personal understanding of Savic-Gecan’s restive choreography. Here, I could speak about how Untitled, 2023 is a grand critical gesture, one reflective of our changing socio-political infrastructure—about the automation of human life that comes with AI programmes, about increasingly hierarchical chains of labour associated with this digital outsourcing, and about how, in our technologically driven age, our cognitive lives are becoming evermore segregated from the empathy of the physical world. Rather than using Savic-Gecan’s to read a more general surround, here I want to end with a quick thought on his affective blurring of formalities.

Untitled, 2023 fundamentally disturbs my presence; it is a strange feeling to be provoked by such nothingness. Made thick and restive and almost auratic, to me this sensation lies in the way Savic-Gecan blurs ephemeral thinking and material methods; conjoining AI automation and the physicality of the gallery’s constituting parts—its architecture, its archive, and the active bodies that oversee its artworld operations—to demonstrate how an existence is always more than a singular, compartmentalised thing. In other words, how an existence is never just conceptual nor just a material thing but something composed of numeral relational layers, apparent and otherwise; something wholly interdependent. In activating the gallery’s emptiness, Savic-Gecan gives its interdependent layers a new sense of primacy, allowing me to feel all that is overlooked in the very nature of its being. And, in this way, Untitled, 2023 not only inverts a modernist logic of segmentation but co-opts it, making the nothingness which constitutes a being newly resonant.

Exhibition information: galeriefrankelbaz.com/798/exhibitions-tomo-savi-gecan-untitled-2023