Jack Evans’ debut solo exhibition ‘Fear of the Dark’ has opened at Soup.

Evans is a British visual artist and sculptor living and working in London. He received his BA (Hons) in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins in 2015.

Evans has long been interested in the sociological, political and cultural responses to subjects that suggest looming existential threat and global catastrophic risk. The uncompromising advances of capitalist and consumer society, the unavoidable consequences of the climate crisis or the inherent dangers of unstoppable technological progression all manifest in sculptures and installations questioning the proliferation of faux-retro leaf block screen-walling, the merchandising of crumbling monuments, the shuttering of Blockbuster video or even the impending extinction of the banana.

Borrowing from the visual language of post-apocalyptic popular culture, heavy metal album covers, video game design, archaeological excavation and the architecture of fallen civilisations, Evans situates his practice in the present whilst employing both contemporary and nostalgic insignia. These familiar signifiers add further imminence to the foreboding threats, forcing viewers to confront true-to-life narratives that perhaps have yet to filter through to the broader public consciousness, through objects and imagery that they recognise and understand. The artist’s use of common building materials – concrete, iron, plaster, polystyrene – imbues each artwork with a relational tactility, while also imitating and distorting certain decorative decisions one might make in the home. Meanwhile, his marriage of traditional sculptural techniques with emerging digital technologies such as 3D scanning and printing or CNC routing allows Evans to produce complex, confounding contradictory objects that foreshadow a future where all labour is controlled and carried out by machines.

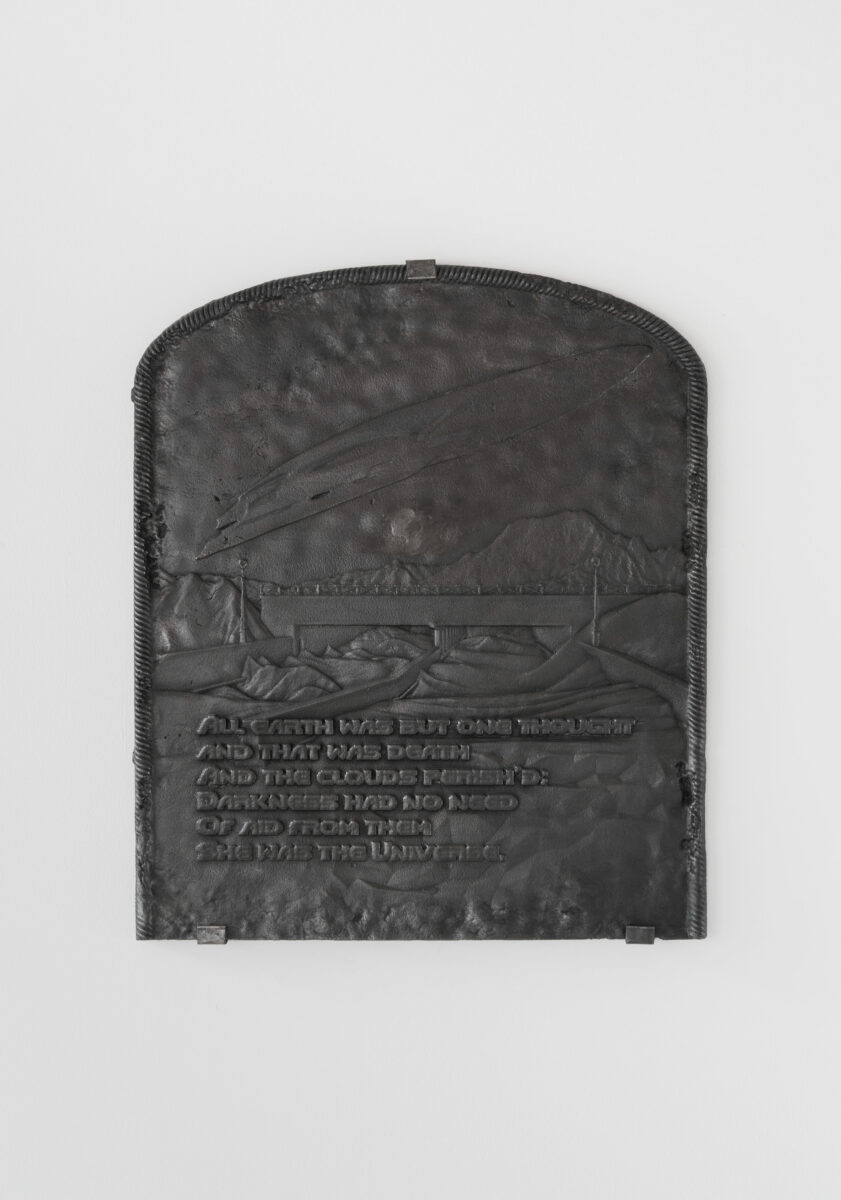

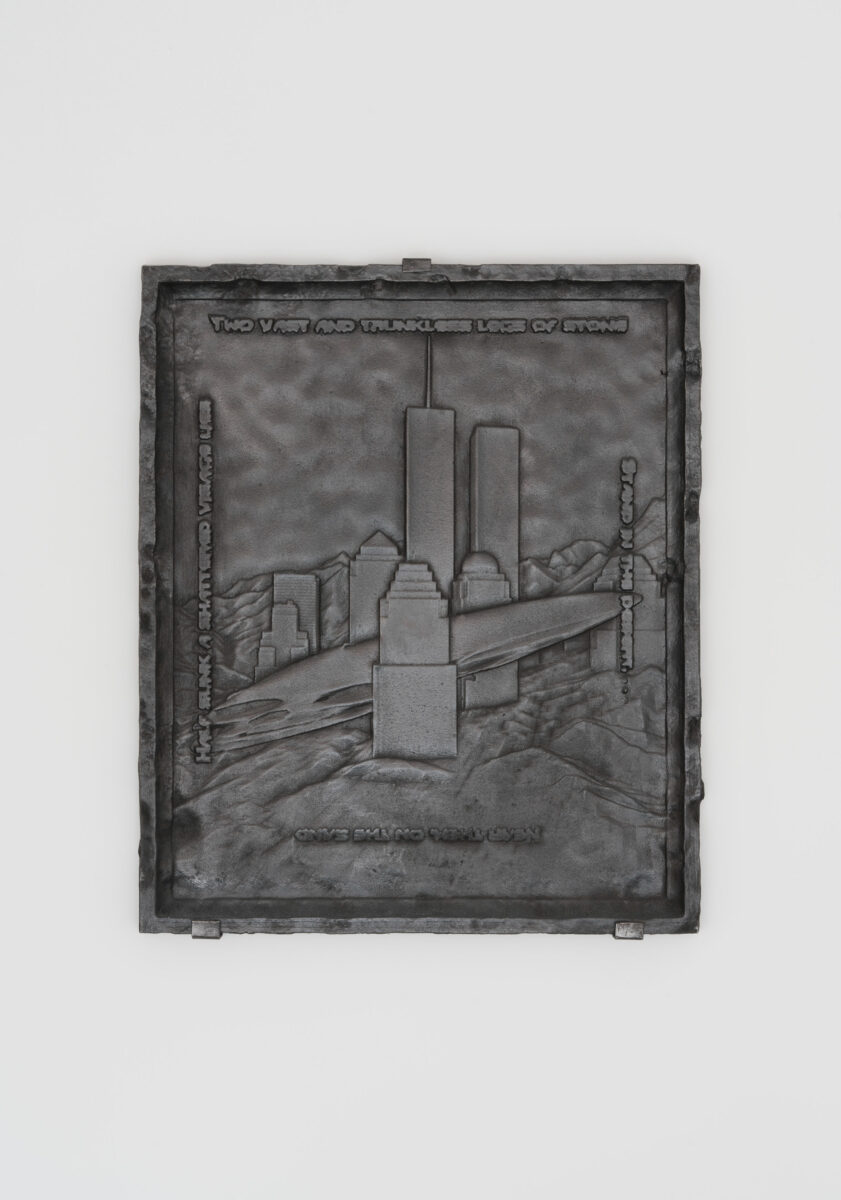

For ‘Fear of the Dark’, Evans transforms the gallery space into the site of a recent apocalyptic occurrence or extinction event. The smoke-stained ceiling is scarred by bright white shadows, evidence of the as yet unspecified incident. Outlines of the gallery standard strip lighting, since removed, recall the signature nicotine staining left after years of prolonged indoor cigarette puffing. In their place, two wrought iron chandeliers illuminate the gallery with the flickering light of twelve candles, transporting the viewer back to a pre-electric era, to a primal existence reliant on fire and flame, a new dark age. Lining the walls are three blackened cast-iron panels, their scale, shape and means of production reminiscent of firebacks Evans has observed in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. Placed at the rear of fireplaces – to protect the stone or brickwork behind and to project the heat of the fire forward into the room – these now-antique artefacts invariably incorporated relief decoration of crests, coats of arms, initials and inscriptions.

Here, however, each panel depicts an event that occurred during the artist’s late childhood or early adolescence, events that significantly formed his worldview and exposed him to immediacy in which previously incomprehensible are rendered in reality. One scene features the twin mouths of the Parisian Pont de l’Alma tunnel where, in the early hours of August the 31st, 1997, Diana, Princess of Wales, was involved in a fatal car crash whilst being pursued by a pack of paparazzi. Another, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, that no-longer-standing site of the September 11th 2001 terrorist attacks which claimed 2,997 victims between New York City, the Pentagon and United Airlines Flight 93. The third, the twin headstocks of Clipstone Colliery, a coal mine on the outskirts of Evans’ home town of Mansfield that at various points in its 81 years of operation employed 1,300 local people, before it finally shuttered in April 2003, now stand as decaying monuments to both an entire industry lost, and to the climate damage caused through carbon fuelled industrialisation.

All arise out of a surreal hellscape, overlooked by a somewhat pixelated depiction of Indonesia’s Tambora Volcano, renowned for its 1815 eruptions, the largest in recorded human history. The immediate death toll of 71,000 people was figuratively and literally overshadowed by the millions of tons of sulphur that entered the earth’s stratosphere, causing climate anomalies in the following years and famine across parts of Europe and North America due to failing crops and the decimation of livestock. Such death and destruction, in the vanitas or memento moritradition of employing morbid symbolism to signify the transience of life and the inevitability of our mortal end, is denoted by a recurring skull rendered in anamorphic perspective.

Identifiably appropriated from Hans Holbein theYounger’s ‘The Ambassadors’ of 1533, which hangs in The National Gallery, Evans’ skull is, infact, the result of scanning and digitally manipulating a genuine human skull.

In June of 1816, known as the ‘Year without a Summer’ due to the effects of the Tamboraeruptions, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his future wife Mary and her stepsister visited Lord Byron during his self-imposed exile to Lake Geneva. During the trip, Mary wrote the initial draft of what would become ‘Frankenstein’, while Byron penned ‘Darkness’, an apocalyptic poem directly reflecting on the year’s environmental disturbances and apocalyptic premonitions. It was Shelley who would, however, go on to write arguably the greatest apocryphal tale attesting to the unrelenting ravages of time, the impermanence of empire and mankind’s insatiable desire for power, 1817’s ‘Ozymandias’.

And so, carved on a period-appropriate door Evans fashioned from salvaged remains of 227 East Street’soriginal floorboards, is the cry of Shelley’s hubristic ruler, a portent proclamation all artists must surely empathise with:

“Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Jack Evans, Fear of the Dark, – 28th October 2023, Soup