There’s quite a specific idea of Sarah Lucas in the public imagination. It’s a kind of gritty androgyny; crude, tough, that’s swaggering and scoffing back at you. Like her Self-Portrait with Eggs (1996), she’s mid-man-spreading on a chair, looking at you like: ‘And?!?’

Our ideas of Lucas have been stuck with the 90s art scene, since she’s so often referred to by her involvement with the YBA, the infamous Young British Artists at Goldsmiths College, where she exhibited her work in Freeze in 1988, curated by Damien Hirst. Also referred, to is her intense friendship with Tracey Emin, where she and Lucas staged a kind of art ‘happening’ with The Shop, selling things like ashtrays with Hirst’s face on the back of it, or gobby slogans on trinkets and t-shirts.

That’s the gist of how we’ve come to understand her. But this latest show, Happy Gas at Tate Britain, which brings her work together from over four decades, (right from her earliest Bunny, to 16 new works, some of which were only completed a few weeks ago), gives us a fresher take.

Her YBA connection doesn’t feel as relevant anymore and is barely mentioned in the show. Lucas actually felt sidelined by the men in the group who were getting acclaim at the time, and she was pretty annoyed about it; as she discussed in Olivia Laing’s book, Funny Weather.

And really, the lewd ‘shock’ factor of her work — that she’s usually associated with — isn’t particularly shocking to a new generation who will be engaging with it when it opens. Partly because doom scrolling for 5 mins on your iPhone can provide more gut-punching imagery to an already chronically online, anaesthetised generation. And partly because fourth wave feminism has already been underway for years, where once obscure academic concepts like ‘patriarchy’ and ‘internalised misogyny’ now have fully entered the public lexicon. Her once radical feminist offerings don’t feel difficult to look at today.

But what I think the exhibition does well is to show how Lucas’ work has evolved since the 90s. And, really, shows what she does best: which is to lay bare what it’s like to exist — from youth to old age — in a female body in Britain; from the 1990s, to today.

So you start in the first room, where it feels like this unleashing of how pissed off she is about the treatment of women in Britain. At the time, in her mid-20s, she was engaging with texts like Pornography, and Intercourse by the American feminist Andrea Dworkin, who was a radical and polarising thinker back then. And you really feel that she’s incensed by it. Dworkin wrote lines like:

‘a woman is not born: she is made. In the making, her humanity is destroyed. She becomes a symbol of this, symbol of that; mother earth, slut of the universe; but she never becomes herself because it is forbidden for her to do so.’

Sarah Lucas is very good at identifying and pulling apart these misogynistic tropes from British culture. She then boils them right down, and hands them back to you as these genuinely funny ‘upcycled’ caricatures — and you don’t really know whether it’s funny, abject, attractive, or serious. Maybe it’s a cocktail of the lot.

In the first room, you can see she’s looking for these sexist slurs in British language (on one of the walls, she lists out swear words associated with women, as well as men, homosexuals, that are so vitriolic). And she’s also looking for it in images. On the opposite wall, she’s blown up a spread of British tabloid pages at the time, where these flagrantly hyper-sexualised, objectified female bodies under a voyeuristic male gaze have quite literally been cut up to isolated body parts (‘pairfect match’ runs one headline, where the viewer is encouraged to match the right breasts to a woman’s face).

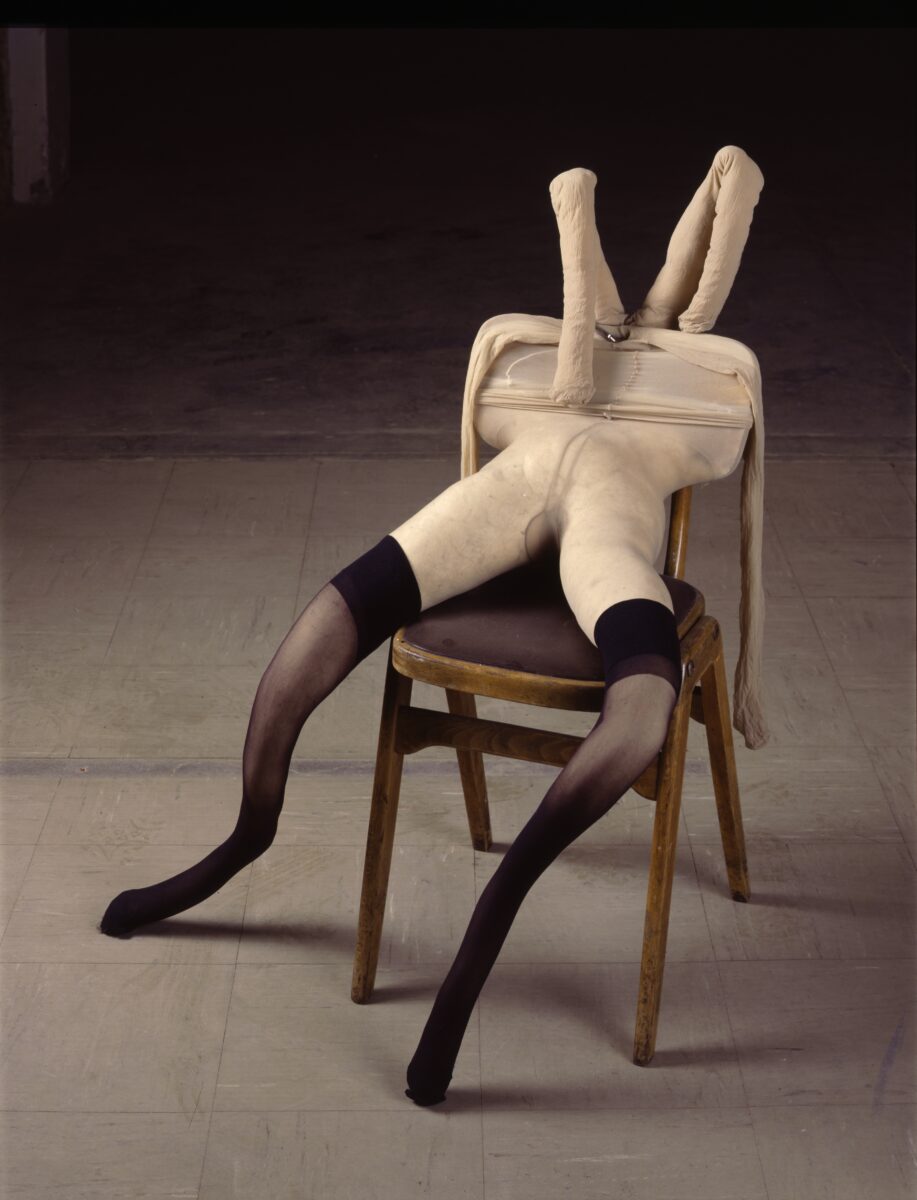

There’s also her first work of Bunny in 1997, that runs with the same thinking. Splindly, sinewed, and stockinged, these open legs are clipped onto a chair that’s stuffed with kapok to resemble mottled flesh, showing what feels like this horrific charade of performative femininity.

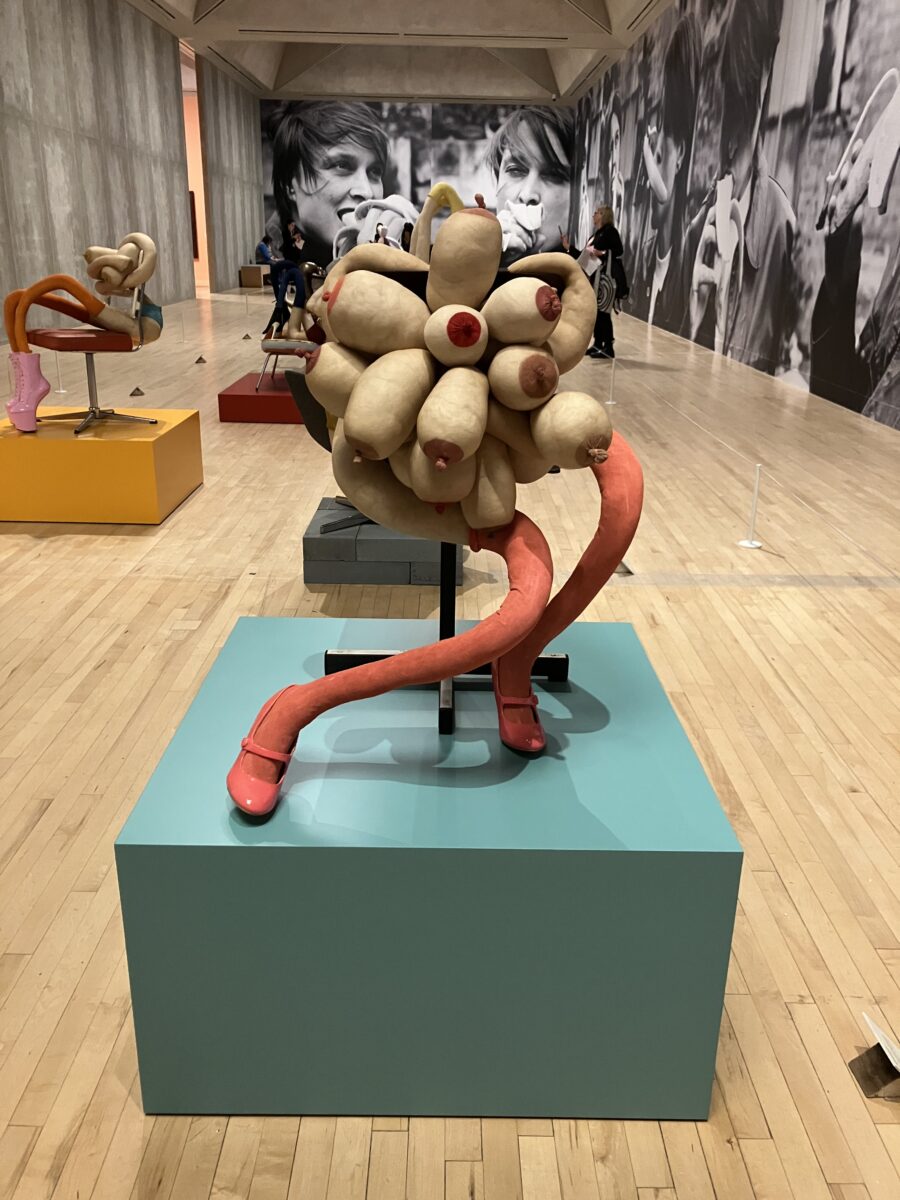

Hop on over to the next room and you’re presented with this whole sculpture court of ‘bunnies’ — with her two most fleshy, the Dorises (Fat Doris, and Cross Doris), some of her most recent, holding court at either end. It’s the most arresting room of the show. There’s clearly a continued commentary of the oppressive male gaze. As viewers, you’re asked to take on the voyeur position, while the bunny sculptures’ tend to look away from you (quite the opposite gaze of Sarah Lucas’ Self Portrait with Eggs 1996). Legs, limbs writhe around the chairs, uncomfortably contorting like pretzels (maybe a visual play on the way women bend themselves to be ‘pleasing’). You’ve got the slurs (one’s titled ‘slag’), as well as the ‘women as an appendage’ trope, standing in for symbols, muses (one’s called ‘goddess’, another is titled ‘angel’).

And while this is all happening — there’s these various bronze casts of black cats prowling along with you, Tit Toms, while you walk through the rooms. Who’s to say why. The ‘black cat plus female nude’ is a trope that’s in Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). Could be the chat noir of Parisian cabaret culture. There’s also the classic ‘lady with cats’ jibe. It also could be just a funny innuendo on pussy. Could be none of them. But like all the works: the only thing you’re asked to notice is what your gut reaction is to it.

There’s plenty of feminist discourse threaded along the show. But it feels much more open than the tough, crude Sarah Lucas we initially expect. There’s a joy and warmth to be found in her representations of the female flesh in this show. Her first bunny in 1997 in the show has given way to more varied, fleshier and older Doris bunnies with sagging breasts and rolls of flesh. There’s bunnies with bright floods of colour. There’s more nurturing iterations too (suggested in the breast-stuffed womb-like sculpture, Mumum, which sounds like a child trying to say it). Maybe this refers back to the paradox of the title: Happy Gas. The dark and light can coexist.

Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, 28th September 2023 — 14th January 2024, Tate Britain