The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance is now open in the National Gallery.

The exhibition sheds new light on one of the most unforgettable paintings in the Gallery’s Collection: Quinten Massys’ An Old Woman (about 1513). Defying Western canons of beauty and rules of propriety, this arresting figure became known as ‘The Ugly Duchess’ after she inspired John Tenniel’s hugely popular illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865). She has remained associated with the world of fairy tales ever since.

The exhibition moves away from the painting’s Victorian afterlife to focus on its original context, stressing how novel this panel was as an early work of secular and satirical art – two areas which Quinten Massys (1465/66-1530) pioneered: the work captures the emergence of the grotesque (in the original sense of the word, denoting the surprising, extraordinary, and comical) as a subject for painting. The exhibition also reveals what this painting tells us of the vibrant artistic exchanges taking place between Italy and the Netherlands at the time and interrogates the Renaissance’s attitudes towards older women and the currency placed – then as now – on women’s youth and appearance.

The exhibition shows that An Old Woman belongs to a broader visual tradition that derided and vilified older women, from the grimacing and pitiful maiolica Bust of an Old Woman (about 1490-1510), lent by the Fitzwilliam Museum, to Albrecht Dürer’s iconic and fearsome Witch Riding Backward on a Goat (about 1500). Beyond the obvious misogyny, these works show that older women afforded Renaissance artists a space for invention and play that depictions of conventional beauty did not allow. Their unruly bodies were metaphors for social disorder, and there is an undeniable joy in beholding An Old Woman trample beauty standards, social conventions, and gender expectations. The image’s enduring power perhaps lies in this irreverence.

An Old Woman has been conserved for the occasion, revealing the full extent of its outstanding execution. The humorous contrast between the painting’s technical refinement and its indecorous subject will shine through now more than ever.

At the heart of the exhibition is the exceptional reunion of An Old Woman with her male pendant, An Old Man (about 1513), on rare loan from a private collection in New York. The two works have only been shown together once in their history, in the Renaissance Faces exhibition held 15 years ago at the National Gallery. Their joint display will allow visitors to make sense of the woman’s flamboyant costume and gesture: she has put on this expensive, scandalously revealing, and by then old-fashioned outfit in the hope of seducing the old man. She offers him a rosebud as a token of love, but his raised hand seems to indicate rebuke. Viewers are invited to laugh at her vanity, lust and self-delusion.

Who are these figures? There has been speculation that the artist depicted a woman with Paget’s disease – a rare illness causing bone hypertrophy. Yet rather than painted from life, she was more probably a fictional folkloric character from the world of carnival, as shown by several prints. In presenting such figures of fun as elaborate portraits, Massys parodied the dignified genre. This will be made plain in the exhibition by contrasting An Old Woman and An Old Man with more respectable double portraits from the Gallery’s holdings, such as Jan Gossaert’s Elderly Couple (about 1520). Massys also drew from satirical engravings featuring unequal lovers, such as Israhel van Meckenem’s The Ill-Matched Couple (about 1480-90).

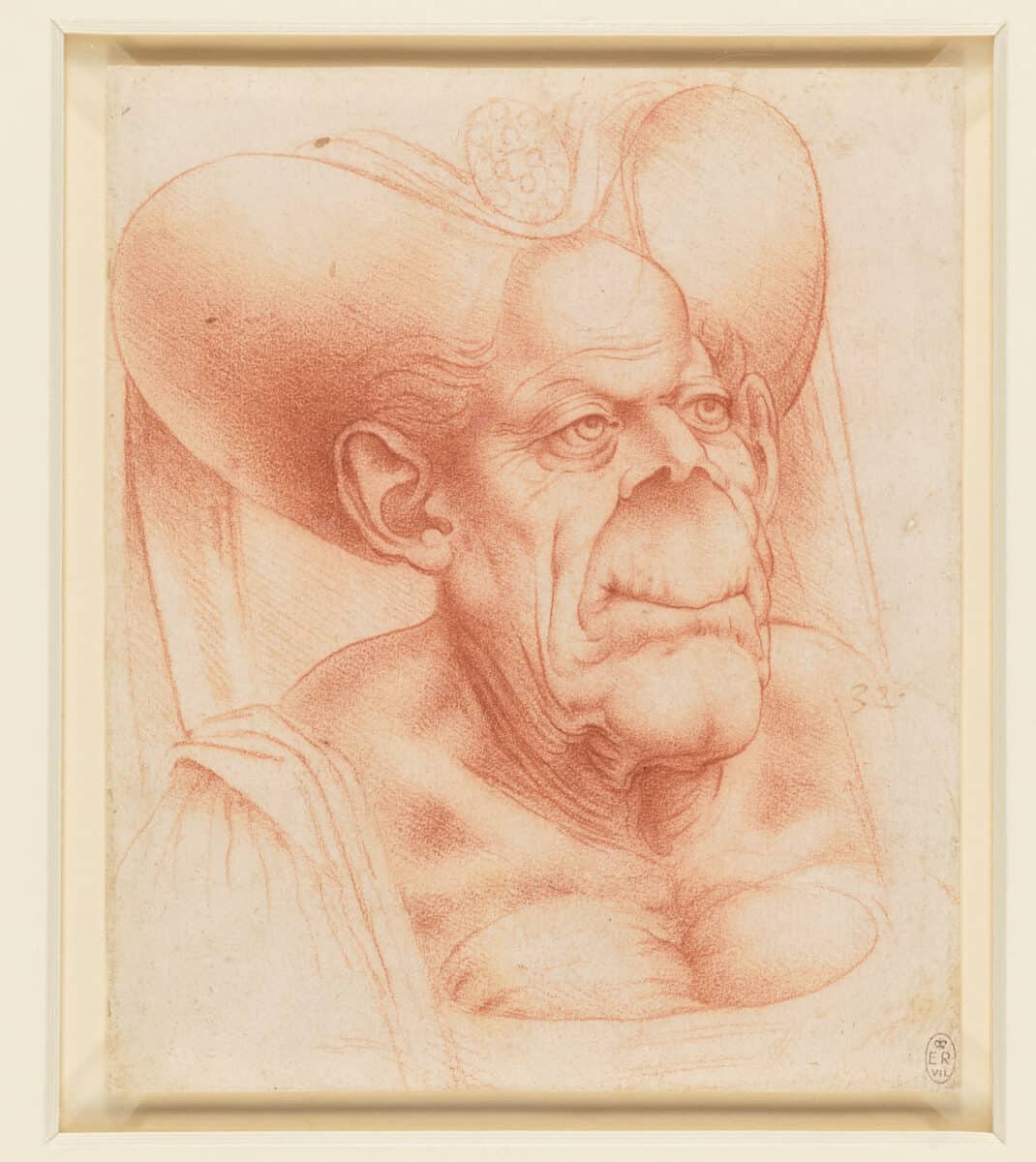

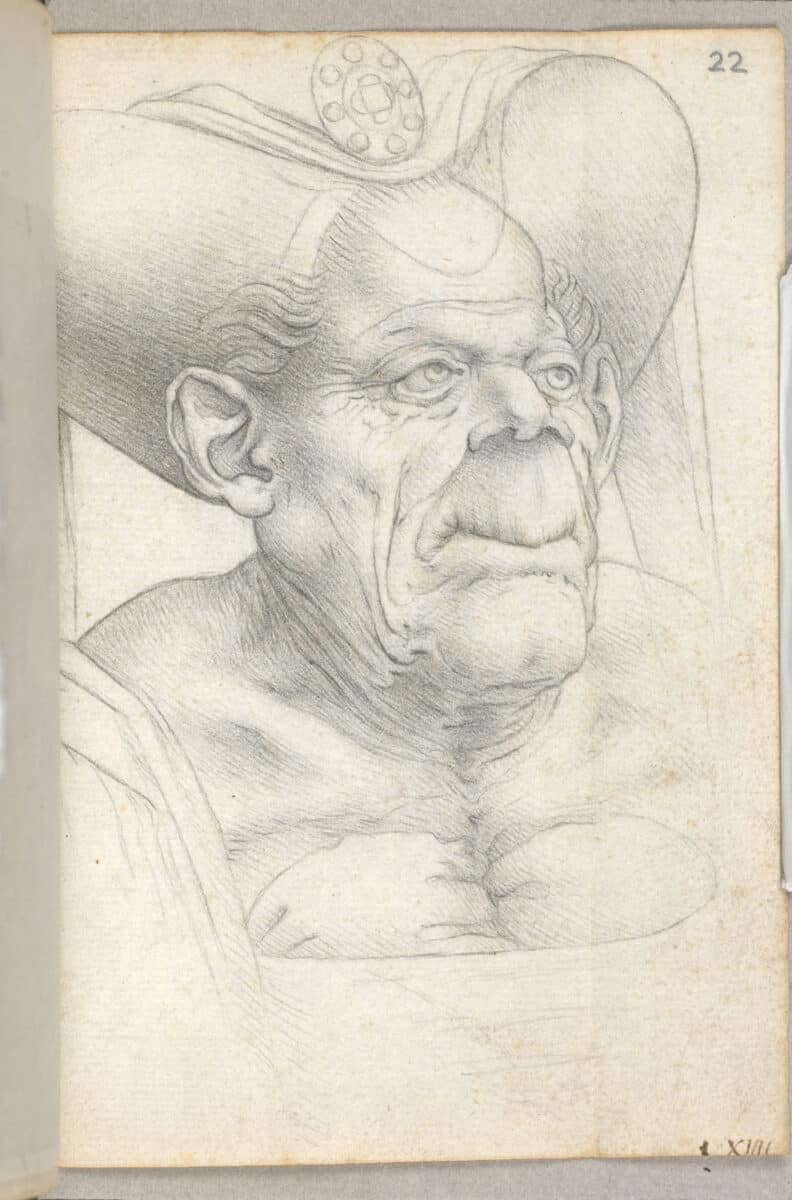

Leonardo da Vinci makes a surprise cameo in the exhibition. For the first time ever, An OId Woman is displayed with two related drawings after Leonardo da Vinci that show the same unmistakable face, generously loaned by His Majesty The King from the Royal Collection and the New York Public Library. Massys probably based his painting on this composition by the Italian master, whose grotesque drawings were famed all over Europe. A small group of sheets by Leonardo and his followers further illustrates the two artists shared interest in the comic, expressive, and subversive potential of distorting the human face.

Emma Capron, Associate Curator (Renaissance Painting) at the National Gallery, says:

‘’The Ugly Duchess’ is an iconic image with a strong contemporary resonance. She has captivated

generations of artists and visitors to the National Gallery. We are thrilled to unravel this work and reunite it for the first time ever with the grotesque drawings after Leonardo da Vinci that inspired it.’

The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance, The National Gallery, -11th June 2023, Room 46 Admission free

Extra events

The Ugly Duchess and the myth of reality: Fiona Alderton leads a tour looking at some of the contrasting ways in which women have been portrayed in Western European art. This event is part of Women’s History Month.

Thursday, 16 March 2023

1 – 2 pm (drop-in)

Thursday, 13 April 2023

1 – 2 pm (drop-in)

New Analysis Reveals That the Famed ‘Ugly Duchess’ Renaissance Painting May Not Depict a Woman After All – Artnet

What a 16th-century painting says about beauty and ageing- FT