Brooklyn-based artist Caledonia ‘Callie’ Curry, famously known as Swoon, is one of the most well-known female Street Artists in the world.

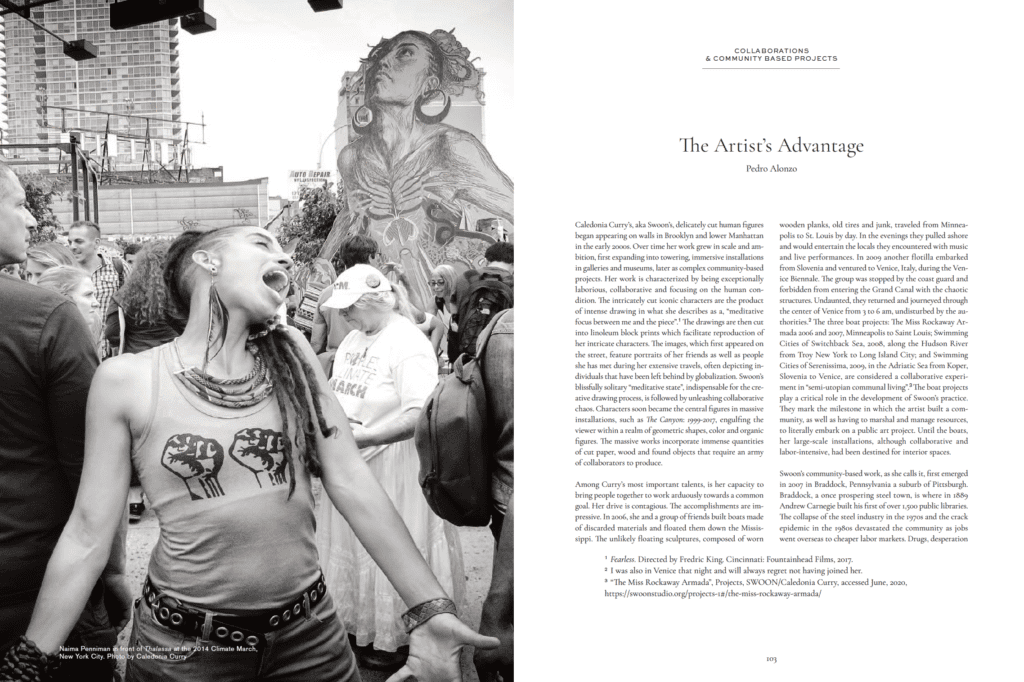

Trained as a printmaker, Curry came to prominence in the early 2000s, on the forefront of New York City’s early Street Art movement, for her large-scale wheatpasting of human figures. While Curry has been based in Brooklyn for the last two decades, her delicately drawn and meticulously cut paper interventions could be found across urban landscapes throughout New York City boroughs and around the world within doorways, on brick walls, between windows, and towering above city streets.

While wheatpasting without permission, Curry was invited into indoor art spaces and worked with large teams to create elaborate paper-cut installation art and site-specific sculpture. This movement allowed her more time and tools towards installing, as well as providing a space to create a new scale of works, many of which are held within the collection of art institutions worldwide.

Over the years, Curry has maintained a studio and art practice while collaborating and spearheading community-based projects that discuss issues from ecological disaster to social crisis. In 2010, when a devastating earthquake hit Haiti displacing hundreds of thousands of people, Curry and collaborators responded by building a community center and single-family homes, all of which were designed and adapted with input from the community.

In 2015, Curry founded The Heliotrope Foundation, a non-profit organization, whose restorative mission is motivated by the belief that, “that the creative process can and should be a part of how we heal, rebuild and move forward after natural disasters, economic devastation, and moments of social crisis.”

Other community endeavours include, ‘The Music Box,’ a musical village based in New Orleans, which served as a playground and laboratory for local community and visitors, and a longtime neighborhood revitalization project in North Braddock, Pennsylvania that includes ‘Braddock Tiles,’ ‘Donnelle’s Safe Haven,’ and ‘The Sanctuary.’

Curry continues to create, engage, and adapt by exploring new mediums and ways to promote activism and imagination. A new monograph entitled ‘Swoon. The Red Skein’ illustrating the last decade of her work and will be available Fall 2022.

Phillip Edward Spradley: Your wheatpasting practice was an ode to New York City and other cities you would visit. These informal interventions developed meaning in people’s daily lives because they live amongst the work, it makes people pause within their usual landscape and consider connection. What were your hopes and surprises in creating these spaces over the years?

Caledonia Curry: So I think in the beginning, I mainly just had this really strong feeling, is that all there is about studio art and art that was just like, okay, here’s my square that I made on a wall. And I love squares on walls, but I still have this feeling that because I am so dedicated to creativity and trying to forge a relationship between creativity and daily life, I feel like the thing about pasting on the street, that was just that very first impulse when I was like, wait, but I love the city. And I love interacting with people and how can I make something that doesn’t try to separate those strands, but that weaves them all together?

And I was a kid from a small town and I was a kid that didn’t feel welcome in a lot of places, whether or not I was, it just how I felt. And so I think I also kind of knew that I was making stuff for me, for the person that was just like, I know I can walk down these streets, I know I can experience art. But when I walk into a museum or a gallery, I am overcome by this sense that everyone’s staring at me and I shouldn’t be there. And so there was just this feeling of knowing what was interesting for me and what I gravitated toward and then just trying to make my work live in that space.

P.E.S: You wanted to make change in the world and decided to use art to do so. Can you recall how you first navigated to this space of where art meets activism?

C.C: I think pretty much, as soon as I started to work outside, there was this sense of, “Okay, I’m doing something illegal and why is it illegal?” And starting to think a lot about city walls and public spaces and advertising, and who gets to sell the visual space of the city and to whom and for what purpose. And so I think that there was this kind of inherent politicization of that kind of action, which I think was not even intentional at first honestly.

I think I just was drawn to the street pasting really in kind of an instinctual way, but then it kind of opened up this whole can of worms. And so once I started asking those questions, I think a lot of other questions followed. And so the big one which was happening for me, which was also happening for a lot of people at the time was about public space and the uses of our cities. And I remember learning about the Billboard Liberation Front and reclaim the streets, which was this movement that started out of an anti highway protest movement in England, I think, but that became about this kind of revelrous public space taking kind of movement that was also about making spaces be open and safe for demonstrations and protests and diverse uses and public participation in the idea that a public common is really necessary to a healthy civic life.

And so I think that was the kind of real nexus for me. And I remember throwing a street party one time, an illegal street party and that being the moment that I first started to try to organize a group of people to do an action together. I guess I did some billboards before that, but anyway, that was just those early kind of moments of organizing people. And then also it was post September 11th and the kind of anti-war movement was blowing up in New York City and forgive the use of that word, that phrase, and so it was just really kind of natural that all of the work that I was doing would kind of dovetail into a political movement, which would then start to ask these kind of questions about where art needs activism.

P.E.S: Your work is enticing because of the care you place on people, whether you are illustrating them or you are assisting them to better their quality of life. There is so much joy, beauty, and exhaustion that comes working at these intersections. What is a common method of interaction that keeps you engaged in these realms?

C.C: So I found really early on that when I would be deep in the studio for a very long time, even though I was drawing portraits and really kind of spending that time looking and feeling connected to humanity in an abstract way through drawing the portrait, that it could be a little isolating, and that I would just get lonely and get antsy, and also start to wonder those questions about, is this enough and does this matter to people’s lives, and are there ways that I can be going deeper with what I’m doing? And so I would toggle back and forth.

And after a while alone in the studio, I’d be like, “Okay, what’s a project that I can work together with people on, in a space that feels like it really matters and is necessary at this moment?” Yeah, like you said, it can get really exhausting. So after a while I was really working intensively with people. I would have a deep need to go back into this really quiet space.

I think the thing that always keeps me returning to that way of working is, I guess, the feeling that something really is getting created, that there’s something that happens when people work together, which becomes greater than the sum of its part. And there’s, I think, generally speaking, no greater meaning than communicating and connecting with other humans. Even though I find myself being a loner sometimes, and literally alone on the side of the world, at the end of the day, I feel like the stuff of life is about human connection. So when the creative process can be an agent for deeper human connection, it’s a good place to be.

P.E.S: Can you describe what initially drew you to Braddock, Pennsylvania and how you have come to make roots there by investing in the local community?

C.C: … Braddock. Oh my God, what a wild ride. I was first drawn to Braddock because I was part of an arts collective. One of my very good friends in a collective wanted to work on urban farming, and was feeling like that wasn’t possible in New York. Then she got an invitation from the mayor, actually, who was inviting people to try to work on things in Braddock, because they were just in the throes of demolitions,

And the town was being bulldozed. The rust belt kind of post industrial collapse was just continuing to drain the life out of this town, and people all over the country were trying to figure out ways to engage that. One of the ways that started was this mayor, John Federman, who was thinking about people who could help save some of the structures, and people who could work on arts projects and farming projects, and just really any kind of projects that would tackle the direct challenges that were being faced, and could bring some outside energy.

There was the feeling that it was pretty hard to survive day to day, much less think of a creative solution as your own neighborhood is being bulldozed. I think there was a little bit of a feeling of, “Hey, you’re over there in New York City, getting squeezed into this tiny amount of space, wishing that you could grow tomatoes.” Here we are over here with 50 vacant lots and not enough time with what to do with them. That was how that started.

Then the project has gone on for over 15 years and it has changed identities many times, but the thing that I’m really, really proud of and really excited about is that we’re finally getting the building into the proper hands. I bought a church, an abandoned, falling down church many years ago. I worked in various ways to try to rehabilitate this building, and did all different kinds of projects involving the community in various ways.

I finally came to the conclusion that it really was going to have to be somebody in the community full time that was the real steward of the project. I ended up meeting this woman, Rhonda Davis Moore, who started a project called the Za’kiyah House, that is safe, transitional housing for people coming out of prison and coming out of homelessness. I have a lot of personal reasons why that is something that I feel really invested in. We just are in the process right now of repairing all the windows so that we can hand the building over to the Za’kiyah House.

In some ways, for me, that will be the end of the project, although my nonprofit Heliotrope Foundation will continue to be involved for indefinite to be a cheerleader and a support system for the Za’kiyah House, as it continues to grow into its work and community.

P.E.S: Your practice is motivated by responses to situations and needs. The architecture of cities empowered you to make site specific art, natural disasters had led you to a country to rebuild, and discovery of family history has prompted you to give back to underserved and overlooked communities. How do you approach the end of an engagement? Are there conditions and perimeters you set for yourself when approaching a project?

C.C: Wow. The end of an engagement. I have to say that this has not been my strong suit. I think that I’m learning boundaries over the years, and perhaps now I find a way to… No, no, I think I’m still not great at it. The work that we started after the earthquake is still, in some ways, going. The work in Braddock is still leading up to a closing place, but there has not been a hard stop on many of the projects that I have worked on, particularly the ones that I started.

There are projects that I did, for example, in Philadelphia, with Mural Arts around addiction and arts therapy. I was being hosted by Mural Arts, and they were like, “Okay, here’s our parameters,” and they set that in place, and I was able to work within that. But when I have to set my own parameters, I’m really not good at ending things in a clear way.

I have to say, even when we went down the Mississippi River on those rafts, it was an unforeseen disaster that ended the project. And at the end of the day, I was actually grateful. The boats actually got burned down because they were parked somewhere where people could access them, and I think people arsoned them for fun.

And at the end of the day, I was like, “Oh my God, we weren’t going to stop that project there,” and it was about to get a lot more dangerous and hectic. And in some ways, I was grateful that the world and its circumstances stopped it. And actually, it’s interesting. I think you asking this question makes me think that that’s an area that I need to work in because… Kind of understanding how things end and when they should end.

In one way, it’s something I’m proud of that I really stay with things, and I really let them change and evolve, and I definitely have to quit before it’s over. But on the other hand, I think it’s probably healthy to think a little bit more about how things end. So anyway, thanks for that.

P.E.S: You’re currently developing a feature length film. Can you share what drew you down this path of storytelling and the choice of using film as a medium?

C.C: It’s really wild. One day I just started writing a story, and I thought it was a weird fluke. It felt like something happened in my brain. Honestly, I talk about it, it felt like the muses hooked one sideways. And I was like, “Yo, I’m not a writer. Where’s this coming from? You guys threw this through the wrong channel or whatever.” But I have since discovered that that happens. Once a year, usually around when I do my silent meditation, after a week of meditating, I’ll just start erupting with these stories in my head, and I have to write them down. And then I’ll be like, “Oh, that’s a complete movie.”

And so it’s this weird thing where I think I’ve been a working artist for 20 years, and I just try to stay really open and really open to what’s happening, and I just try to really let those forces lead. And so that’s how I started working on this movie. That I started writing this story, and then the story wouldn’t go away. And then slowly, I was like, “Oh, maybe it’s an animation. Maybe it’s a movie. Maybe it’s… Oh, shoot. Oh, oh gosh, I’m working with actors now. Oh my God.” And it’s blossoming and blossoming and blossoming.

And the story itself is a fairytale fictionalization of some events from my childhood, so it’s deeply personal, and so it has this very strongly rooted place that it’s coming from. And it’s a project that’s been in pre-production for a couple years now, because movies are, they’re a world unto themselves, so it’s amazing how much goes into it. So it’s still just beginning, but I’m really loving it.

P.E.S: Can you tell us about your experience in filmmaking? I imagine that some of your skills with visual reasoning, being a mediator and facilitator transferred towards directing, but what were some elements that you found challenging and became learning experiences?

C.C: Filmmaking is still really new for me. Outside of my stop motion animations, I haven’t completed a film. But I just got back from the Sundance directors labs, and it’s been a mind-blowing experience, just getting this deep into things. And what has been really mind-blowing is that all the work that I’ve been doing over the years is directly translating into directing a film set, that it’s actually not, in some ways, terribly different from all the other large, directing a big installation or collaborating on rafts or any of the things I’ve been doing over the years. The process is very, very, very related. And then the things that I’m loving, but that are very big learning experiences, have to do with working with actors, which I’m adoring. It’s incredible, but I definitely feel like I have a lot to learn.

And then the other day, I had this really funny moment where I burst into tears while listening to some documentary about a television director. And I was like, oh my God, why? What’s wrong? And it was like, oh, because he was describing how he closed his eyes so he could count the beats between jokes of his show, and I was like, oh no, I will never. And I know that it’s not true, actually, but I just felt in that moment, there’s a sense of rhythm and timing and flow of story that people who have been doing this for their whole life have, and how will I ever, ever, ever get that? And I believe that I will, but that’s where I’m really scared.

P.E.S: With all of your endeavors spanning across mediums and spaces, socio-economic empowerment, community organizing, stop animation, filmmaking, printmaking, and museum installations, how do you go about organizing your thoughts and time?

C.C: It is really challenging. I haven’t gotten a diagnosis, but I finally came to think that I probably have ADHD. I don’t necessarily believe that’s a problem. I think that it’s just a structure of mind, at least in my case that my brain needs to be going on five channels in order to just feel comfortable. And so there’s this feeling of okay, this project, this subject, this subject, this project, this project, and I love to dive into things really deeply, but I also really am compulsively almost drawn to dividing myself between all these different thought processes. That’s actually one of the things that I’m really excited about filmmaking is that it takes that tendency, but it can bring it all into one project.

And so that’s been fun and exciting to see that happen. But going about organizing my thoughts in time, I’m not great at it I have to say, and I have a lot of help. I have people who help me in my studio. I have people who help me keep track of my email and my calendar, because the thing is that I find that the true creative work is very formless and timeless. And if I don’t have help to organize the external stuff, I won’t be able to have time to do the soft stuff in the middle. And so mainly it’s just squeaking by and stealing as much time as I can to really get into that primary creative zone where time stands still anyway.

P.E.S: You are coming out with a new monograph later this year, can you elaborate on the title of the book and what are a couple of the images and stories that you wanted to share with people?

C.C: Yes, I just finished this monograph and it’s called The Red Skein. Because I was thinking about, when I was talking with Drago, the publishers, this thing we all kept circling back to is this idea that the book will feel like a labyrinth because there’s a lot of layers to my work, and we’re trying to make this dense space. And so of course, thinking about the labyrinth, then I started to think about the minotaur and then this important piece of the story, which is that how Theseus survives labyrinth is because Ariadne sneaks him this piece of thread, and it’s the thing that allows him to find his way back through the maze. And it’s this act of love, and it’s this just a connecting piece.

And so when I was making the book, I thought, okay, let’s just embrace that metaphor, and let’s imagine that the book itself functions as that thread to connect all of the different dots. Because it is complicated, I think, to understand any artist’s entire journey. And so I’m hoping that this can be one of those spaces that holds as much of the journey as possible, even though, of course, it’s 10 plus years packed into a few hundred pages, so it’s very edited.

I guess the first thing that pops to my mind is I was able to just show certain connections. Years ago, I was doing this really fun event that we called Pearly’s Beauty Shop, and it was supposed to be a fundraiser, but it ended up to just be super fun, where artists would do a nail salon and hair salon, and we would do people’s hair and nails and makeup and make this cookie party and dress everybody up, and it was this beautiful, festive thing.

And then years later, I was working down on Skid Row in Philadelphia, and we were just thinking about art therapy and connecting with people who were living homeless and living on drugs and just having these really intense life experiences. And I was like, “Oh, you know what would be so nice?” I just remembered Pearly’s, and I remembered how much I loved just sitting with people and talking, the kinds of conversations that we would have while we were doing hair and nails. And I was like, “We should do manicure day.” Also, it’s hard, if you’re living homeless, it’s really hard to keep your hands clean and look presentable, and everybody wants that dignity. And so it was one of those moments where this thing that had been this really super, just fun, really joyful thing crossed directly over into this work which felt even that much more deeply meaningful. And so getting to show images like that side by side in the book is a nice opportunity. Nice experience.

P.E.S: At this stage in your practice, your career, your life, what does art mean to you and what are you most excited about for the future?

C.C: It’s funny because, even after all these years, I think that art is something that I believe in even more now than I did when I was a kid. I think when I was a kid, I kind of had a hunch instinctively that it was something magical and meaningful. And another way, it was just a way to get out of my small town or get approval, or it sort of functioned for me in these different ways. But the longer that I make art, the more that I kind of see that there is this kind of actual transformative magic that can become kind of awakened and embedded in objects and moments. And so it’s like the longer I work, the more I believe in it and the more that I believe that there is something truly transformational, something that’s so much more than the sum of its parts that can happen within it.

And the thing that I am most excited about is the storytelling piece and the films, and just seeing what that is. It kind of feels like… I almost have this funny feeling as though I’ve traveled the entire history of art in my lifetime, that I started out making mud houses in the backyard when I was this little kid, with sticks and rocks and dirt, and then I started painting, and then working on sculptures and installations and just kind of fully chewing my way through all of the different ways that humans can make art, particularly visually. And so something about film being something that later enters the canon and I’m kind of entering it a little bit later in my life, it just feels kind of ripe in a way, and I’m really excited to see what opens up in there.

Follow Caledonia Curry on Instagram @swoonhq and to learn more about her artistic practice visit her website. To learn more about her non-profit visit The Heliotrope Foundation website.

To preorder ‘Swoon. The Red Skein’ visit here.