Kristof Santy’s sudden transition from relative obscurity to art world fame is increasingly rare. It isn’t often that an unknown artist, working in relative secrecy, creates such a cohesive and accomplished body of work just waiting to be discovered. For Santy, this magical breakthrough moment occurred in 2021 when Thomas Serruys approached the Flemish 35-year-old for a studio visit that would lead to his first show. From this moment on, the secret was out and Santy’s work caught the attention of international galleries including Unit London where he currently has a solo exhibition entitled La Grande Bouffe.

Entirely self-taught, Kristof Santy lives in the Belgian city of Roeselare and works from a studio in his garden. He is a true original, maintaining a deliberately simple life that involves cycling rather than driving, regular family meals and always painting barefoot. He allows his work to speak for itself, avoiding impressing narratives upon the paintings and instead encouraging the viewer to draw their own conclusions. In terms of subject matter, Santy turns to the small things that populate his daily existence and finds joy, surprise and splendour in passing moments often overlooked or forgotten by others. Both his demeanour and his artistic output are genuine and autunitic. His work is entirely self-motivated, without hopes of reaching a particular audience, nor receiving the spoils of sell-out shows.

On meeting him, I was struck by his openness. He was calm, warm and straightforward, seemingly unphased by the sudden transformation from factory worker who paints on the side to subject of a solo exhibition in a London blue-chip gallery. This very attitude, along with his commanding, bright and refreshing paintings, left me with the feeling that Santy is headed for greatness.

You worked as an artist almost in secret for a number of years while employed at a factory. What motivate you to make art during this period? Did you have an intended audience in mind for the pieces you were creating?

I’ve been creating all my life, whether it was drawing cartoons or painting. I couldn’t live without it and it has always been the most important thing in my life. I’ve never had a particular audience in mind and that continues to the present day. For me, it is about the process of creation, that is my joy. What happens afterwards is not the most important thing.

But I had to pay my bills so, until recently, I had a job which gave me a steady income and made it possible to build my studio and buy supplies.

In 2021 you had a debut exhibition at Thomas Serruys Gallery, in Bruges, Belgium. In many ways this was a turning point that led to your work being discovered internationally. Can you describe the shift that occurred and how you came to have this show at Unit London?

It was Thomas who contacted me during the covid period. He discovered my work on Instagram and asked to visit my studio, he was very enthusiastic and proposed a show. For the first time, I felt like my work was ready to be viewed by an audience and I was feeling really confident that I had found my own language.

The show was an incredible success, which led to more discoveries on Instagram. Unit was the first gallery to contact me and I was really flattered by this international opportunity. When I visited the gallery in October, they proposed a solo exhibition and I happily excepted.

Much of your work explores food and experiences from daily life. What attracted to you to this subject matter?

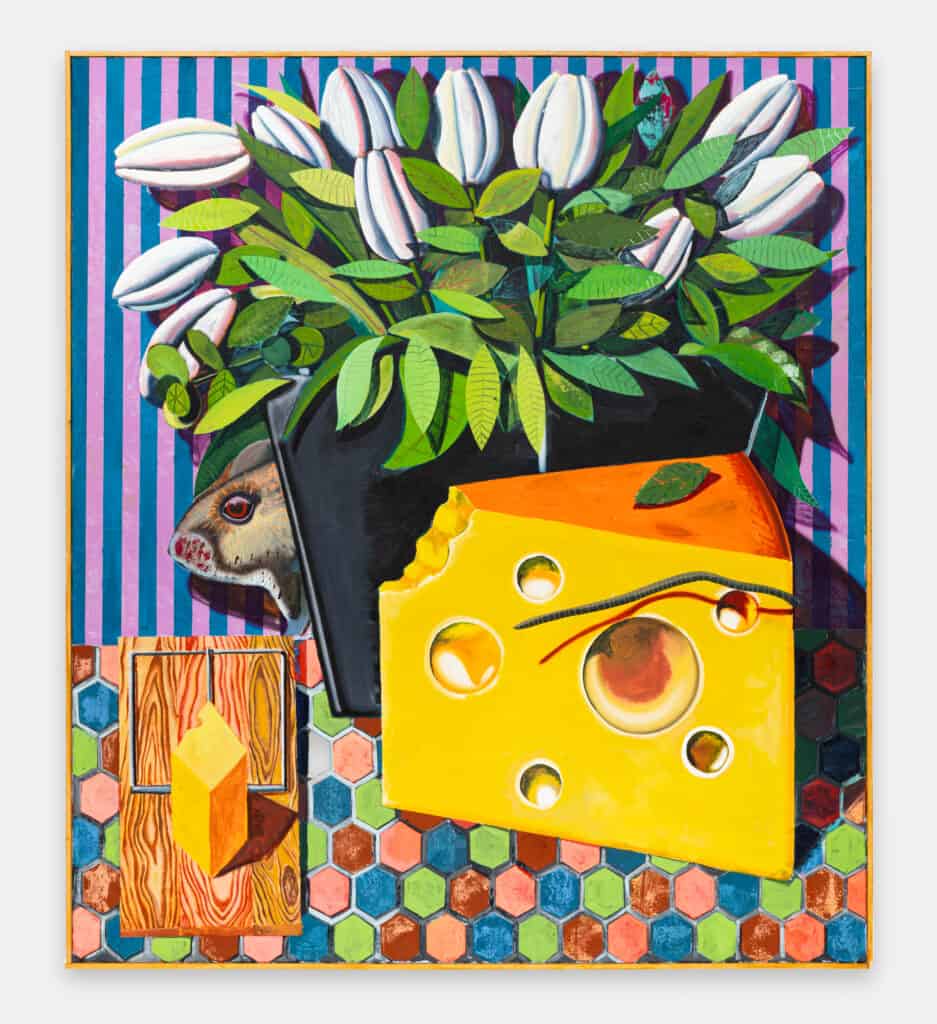

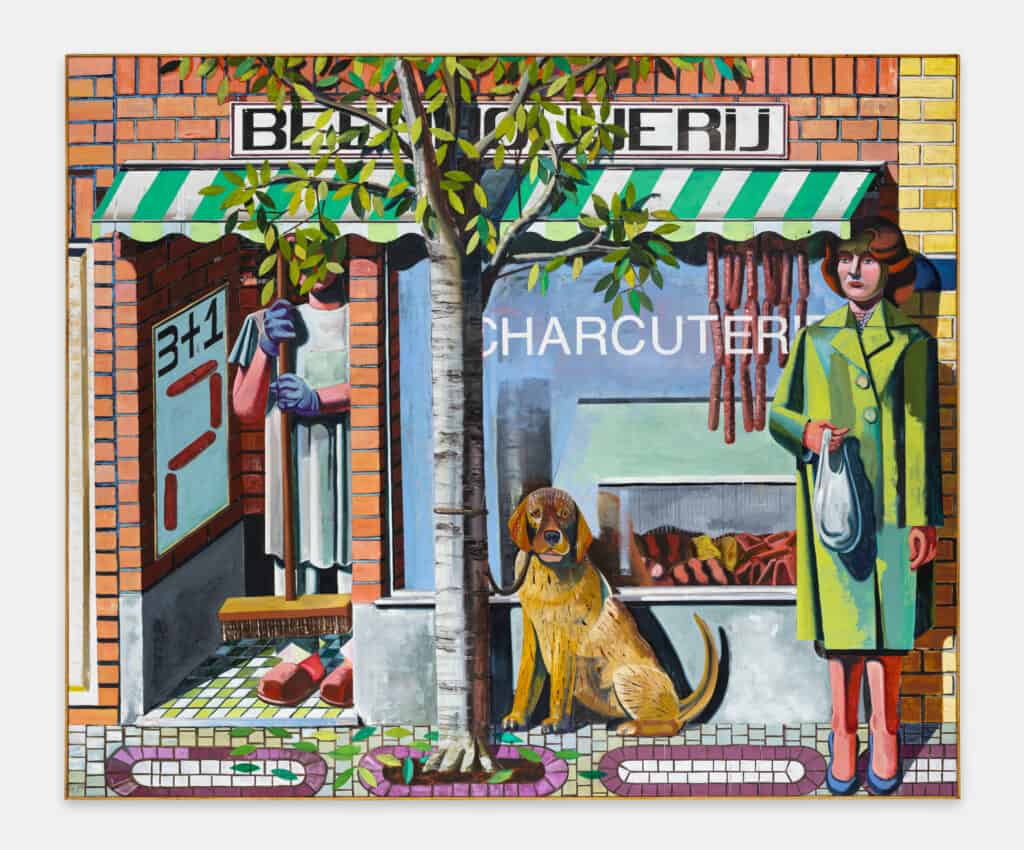

Since 2021, I have been obsessed with painting food related topics. For this exhibition, I applied my visual signature to the theme of gastronomy in a broad sense. The show includes a fishing boat, a butcher shop, a farmer on his tractor but also gastronomic still life scenes and monumentalised kitchen equipment.

Painting these common objects and elements of daily life is almost a route to making them iconic and memorable. Our history is full of iconic images, and we can continue to evolve and produce them in a contemporary mode. A toaster is probably not an interesting subject at first sight, but once you paint it, you give it another dimension. By painting what is on my plate, I solidify the experience in history. For me, it’s all about creating a power that emanates from the subject.

But don’t forget, my paintings are not narrative. I tell no stories; I give no opinion. I just want to show daily life in order to go back to the source of what is important. In my opinion, daily things bring joy to our lives, they are what makes us human.

What’s your process like, do you typically work from photographs or are the compositions largely imagined?

I never start from photographs. I build up my images in an intuitive way. The starting point is always a composition created in my mind. Then I make a sketch based on abstract elements. Thanks to my visual memory, I can immediately refer to a huge internal library and find inspiration: images from the renaissance, modern art, folk art, painters like Braques, Morandi, Klee… everything is in there.

Then, I detach myself from the sketch as I paint. I always say that painting is problem solving. For this, you have to dare to break free from the original idea. I paint over, add, remove. Suddenly the painting takes on its own life and I am only doing what it asks of me. When I get into the rhythm of the painting, it feels so easy.

Tell us about a typical day in the studio. Do you work long hours? Do you find it better to be alone when making art? Do you have any studio rituals to get you ready to paint?

I paint almost every day. My studio is an independent building next to my house, so that makes it really easy to start when I feel like it. I try to have a routine which makes the creating process easier, it’s calming to know what my day is going to look like.

I wake up when my daughter wakes up, I have breakfast and coffee with my family and start around 9 am. I have lunch with my wife and continue painting till about 6 pm. Next, I enjoy some more time with my family and afterwards I love to draw in the evening. It’s lovely to make some drawings after a full day of painting. When I don’t paint, I usually go for a drink in my hometown with some friends, or visit book stores and antique markets. The easy life keeps me calm and happy.

A couple of the works currently on show at Unit London draw imagery from films, in particular the piece titled Beenhouwerij (2022) – could you elaborate on how imagery from films comes into your practice?

This winter I discovered the movie Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Brussel by the Belgian director Chantal Akerman, made in 1975. It’s a hypnotic, real-time study of the daily routine of a middle-aged woman, called Jeanne Dielman. She fills her days with superficial household chores and taking care of her son. Every day she uses the same objects, every week she visits the same stores, cooks the same meals. Her routine seems suffocating as well as reassuring. Most of all, the film made me want to honour the everyday banal objects that we use over and over again by painting an interpretation that gives them power.

Besides films, where do you find both visual and intellectual inspiration for your work?

I sort of taught myself about art over the past few years by reading lots of books and constantly looking for new inspiration. Primarily, I’m influenced by the painter Jean Brusselmans. When I saw one of his exhibitions, it was a revelation. I saw the freedom in his paintings. He was no longer looking for the perfect representation of his subjects, he just painted them in a stylistic, fast and brutal way. This felt like heaven to me.

Domenico Gnoli and Konrad Klapheck are also important references to me, it is probably apparent in many of the perspectives I use. The 70s European Pop-art in general is also something that you can see reflected in my work. But actually, I choose my masters very widely. Frans Snyders for example, the baroque painter who painted all the animals in Rubens’ work, was my inspiration for the fish market. Even cookbooks from the 60s or 70s are a great folk influence that I loved to look at while creating these works.

To what extent do you feel that your work is a reflection of yourself? Having previously been an artist largely outside of the ‘art world’, it appears to me like you have been able to develop a very unique and personal voice through your work.

My work is made of snapshots from everyday life, in order to bring banal objects to life. These elements are so familiar that everyone recognizes and relates to them. If you think about what we remember from other times in history or historic tribes, it is everyday objects. Our museums are filled to the brim with them. People love to see what their ancestors used to make dinner or for hunting. Therefore, I believe that depicting everyday life is honouring the time we live in. But still, there is no narration in my work.

Since 2020 I have been simplifying my life and that is very satisfying. I focus on my immediate environment and love the details of ordinary things. I stay close to home for everything, enjoying my own garden and studio, drinking coffee with my wife, walking through my city where I know everybody, enjoying my cats. I sold my car and I bought a bike. Life doesn’t have to be so overwhelming. Everyday things have such a beauty, I want to stay close to that and show it to an audience.

What can viewers expect from your current debut London exhibition? When brought together, what impression do you think the works might leave the viewer with? What has the process been like putting together this show?

I started on this show in January, focussing on gastronomy still life scenes because it really felt good at the time. I just painted what came to mind and what made me excited to study. I’m happy with the way it turned out. But I never think about the audience, it’s their job to make an opinion. Try not to expect anything, that’s my advice.

What’s next for you following the exhibition at Unit London?

Next up I have a solo exhibition at M+B Los Angeles in December. In March 2023 I have a solo exhibition in Brussels at Sorry We’re Closed. For this show we are also working on a book, that’s really exciting! After this busy period of painting, I also want to focus on other media like etching and woodcutting and pull back a little from the madness.

Kristof Santy’s exhibition La Grande Bouffe at Unit London runs until 6th August 2022.

Find out more about Kirstof Santy: @kristofsanty