Amy Bravo is New York City-based artist who is working on unpacking her direct family history and uncovering ancestral Cuban cultural history while simultaneously working to create a new narrative of understanding.

Growing up in a rather conservative New Jersey suburb, her areas of interest and access to like-minded youth were few, what was widely available were materials to create art and a rich history of stories from both her sides of her family. Bravo’s Cuban grandparents instilled their love of religious iconography, community, family, and horses, which are prominent in numerous works that make up Bravo’s practice.

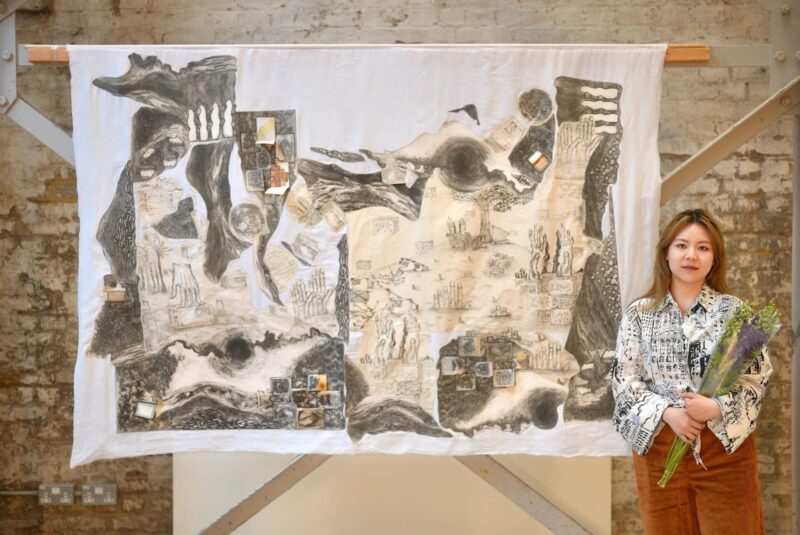

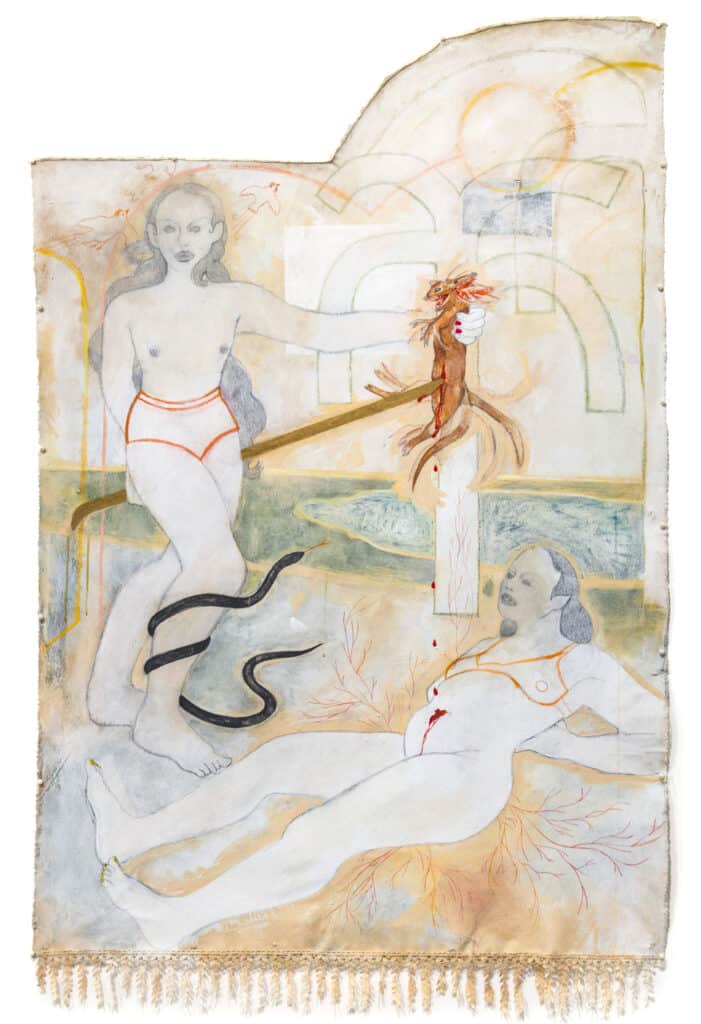

Trained as an illustrator, who primarily worked on paper, Bravo has shifted towards canvas, where she continues to discover new methods of working and new materials to utilize. The figures in Bravo’s work are pioneers, they are constantly searching their environment, or inside themselves, and are glowing proudly as they are on display. The landscapes are fictional as well as distant places that Bravo’s has, for now, visited through words, images, and oral histories. The various materials and miniatures that are incorporated are found objects, taken from her childhood home, or gifted from family, friends, and loved ones.

Regardless of the size of the work or the materials utilized to achieve Bravo’s vision, “Community” is the base of her work. Whether it be nuclear family, chosen, or imagined, the interactions and domain in which these narratives take place come from highlighting the female, queer, brown, latinx communities Bravo is a part of and drive her in a constant motion of discovery and appreciation.

In July 2022 Bravo will relocate from New York City to the Fountainhead in Miami for a residency program that will assist in furthering her research in material and history.

Phillip Edward Spradley: Your work contains a multitude of textures. Between family possession, craft items, and trinkets, you must have a deep treasure trove to pull from. Can you share how these items have come into your possession and what items you gravitate towards to communicate your ideas?

Amy Bravo: Collecting generational objects is one of the ways I attempt to preserve my ancestry and incorporating them into my work is one of the ways I attempt to contextualize and unpack that ancestry.

Most of the objects and collage materials I use are sourced directly from my family home. Because the work draws so directly from familial narratives, it feels meaningful to me to use objects that lived in my home with me growing up, or to at least find very close approximations of those objects.

I’ve become interested in the form of a curio cabinet as an alternative to the archive. The curio cabinet doesn’t attempt to function as a comprehensive record-keeping of familial history, but it is a carrier of objects and ephemera that act as devotions, symbols, stories, and characters. In a way, my entire studio is a curio cabinet, and I’m a figure within it as well, moving things around and building a world through objects just like I did as a kid, playing pretend with the carousel horse figurines, making the ornaments on the Christmas tree talk to each other, turning a pillow tassel into a woman with long hair.

More recently, I used the pillars that held up the kitchen table I ate at every day growing up for a podium to hold a sculpture. The carousel horses that sat in my own curio cabinet growing up have also found their way into the work.

P.E.S: As an artist that works within mixed media, is there a new way of making that you have recently come across and added to your practice? Can you elaborate on how this method or material currently helps with illustrating your language?

A.B: My work has always been mixed media, and I think my work has always wanted to engage with assemblage, and I had done so in various kind of polite ways in the past, making paintings that had a few attachments here and there. But it never really felt like it was going far enough.

I was venturing into sculpture and had made my first standing painting when I was taking Nari Ward’s class at Hunter, and from then on, the works have veered into a place between flat and 3-D. At the same time, I was looking a lot at Belkis Ayon’s work “To Make You Love Me Forever”. I was obsessed with the way it was installed, it looked almost like an arcade skee-ball game, but also an altar. It had this strange formidable presence to it that felt so different from a flat work on the wall. I loved the confusion of space, how the surface of her work had this flatness and depth simultaneously, and how bringing it off the wall in this way played with that even further.

In my recent work I’ve been adding large 3-D elements like a large wood-cut cloud with an inset diorama, a shelf of cement/dirt that juts out from the wall, sculptural frames made with plaster and stucco, etc. They no longer feel like drawings or paintings, but strange set pieces for a play I’m still writing.

P.E.S: Figures in your works seem to be blessed, transcending, and holding on to their space proudly. Elements of Nature and religious signifiers are powerful themes that can be seen throughout your work, which adds to the strength of the figures. Nature and Religion can be mysterious phenomena, almost uncontrollable. Do you allow for much chance and circumstance in your work, or do you attempt to be in control of the entire outcome?

A.B: Chance in the work is everything. I don’t really prepare a lot when I start something. I never sketch a composition. I always end up preferring the sketch to its translation. It’s important to me that there are several moments in the process of making where I feel like I’ve hit a huge wall, and I hate the thing I’m looking at. Finding the way out of those moments is usually an impulsive process, making big moves really quickly, having to over and under correct. Accidental moves on the canvas become ghost images or characters in and of themselves. And when it comes to sculptural elements, I’m barely ever in control.

There’s a bit of a running joke about me breaking all my sculptures multiple times before they get finished. I never took a sculptural methods course, and so most of the time I’m guessing what I have to do with my materials, and I usually get something wrong. But it leads me to these exciting moments of problem solving, having to Frankenstein something together after the initial plan fell apart. You almost always get something new and weird and better out of those crises.

P.E.S: Have you been able to create an accurate space of understanding from the stories that were told by your grandparents and parents? Is there a well-documented linear history and open discussions or are there pieces of time and information that you are attempting to fill?

A.B: Definitely not.

What I have in terms of stories and oral history is essentially just ephemera. I’ve done a lot of work myself trying to piece together a timeline, but there’s so much missing. I know that my family lived on a farm in the small town of Fomento, Cuba, in the Sancti Spiritus Province. They had many siblings to help work the land. They ranched cattle, and rode horses, as most people in their province did. My great grandfather owned a small convenience store in town, which at night turned into a music club. They didn’t really have much in terms of money. My grandparents left in 1949, as Batista’s regime worsened the struggle for small farmers living inland.

They lived in Washington Heights for years, where my grandmother worked as a seamstress in a sweatshop, and my grandfather worked in the phone business. And that’s the gist of it. My Cuban grandparents passed when I was in high school, and we didn’t get enough time to learn from them.

Everything I’ve learned has come mostly through my father, who tells me stories on long car rides, or sends me family photos via text. So much of the oral history is unreliable, and I’m interested in traversing those gaps in the history, opening them up and building alternative spaces within the world of our family.

P.E.S: Families can be difficult and sometimes the biggest challenger. What can be the most demanding part of placing yourself into these histories and into the work?

A.B: I think the most difficult part can be trying to remain honest with myself and not hide in the work. It’s hard to make work that unpacks familial narratives, and then to show that work in public, where others, including your family, can see it.

Sometimes there’s an urge to be overly vague, to self-censor, to keep things buried to a degree. A very Catholic impulse. Resisting that is really one of the biggest challenges I have making the work.

P.E.S: A lot of knowledge can be placed upon a child without them really understanding the cultural or historical significance. The inability to fully access your ancestral physical landscape as well as the verbal language has made you a strong researcher. Artistic research assists in furnishing insight and can also assist making something literally visible. What types of research methods do you incorporate and how does it further inform the art?

A.B: I dig into archives sometimes as a way to contextualize the familial narratives within time and place. I’ve spent a decent amount of time looking at the University of Miami Cuban Photograph Collections. There’s also a postcard database I look at a lot, it has a few images from my grandparent’s town and Province. Sometimes I’ll print the postcards out and collage them onto the work. I don’t like to draw directly from them, though.

Recently, I saw a postcard from Fomento in 1926, featuring a crowd of men on horseback, with writing on it, reading “parte de la caballeria (part of the cavalry)”. After seeing it, I made a work featuring a crowd of female figures riding horseback, and wrote the same text onto the canvas. I used another one of the postcards, of Piedra Gorda, a Fomento landmark, in my piece “The Waiting Room”. The postcard was blown up and printed onto plexiglass, creating a windowpane to a diorama inset in the work.

I’m not interested in copying or translating images of the landscape, but I look at them, and all elements of my research, as additive ingredients to a composite site I’m creating the work in. The site of the paintings is not Cuba. It’s a shadow of a place collected through Google image and maps searches, Youtube videos, memoirs, historical texts, a personal and familial lexicon, and my own imagination.

There is no engagement with or true relationship to the Cuban landscape, because it is a landscape I’ve never been able to physically access. The landscapes I make are vague, caked with patina and performed nostalgia.

P.E.S: Cultural references come to us directly and indirectly and can manifest in the strangest places. Are there signifiers in your work that you find yourself revisiting or that you are working towards?

A.B: Oh, I could go on forever about this.

I’m obsessed with repurposing old and creating new signifiers. There are so many in the work, quite a few of them are signifiers that have a larger cultural context, but hold a unique meaning in my familial lexicon. The horse, for example, is a huge part of my work right now. I got fixated on horses after hearing a story my dad told me about my grandparents. My grandfather Carlos was a gifted cattle rancher. He was a real Cuban Cowboy. When he would go to my grandmother Aida’s home for a date, he would ride the horse owned by her father, Pedro Peña, back home.

According to my father, when Carlos would arrive home, he would “smack the horse right on its ass and send it back,” hoping it would return safely to the Peña farm. If for some reason the horse didn’t show up by the next morning, Pedro would be angry, and my grandfather’s relationship with my grandmother may not have been allowed to continue. But it always made it back. For this reason, I always say that our family was built on the loyalty of a horse. In my work, The Loyal Horse acts as a vehicle and protector for those traveling between life and death.

And recently I’ve latched onto a symbol I created based off of a piece of my mother’s embroidery. She had done a cross stitch on a few tea towels that had the letter “B” for Bravo on it. I noticed the back of the cross-stitch looked a bit like an architectural drawing, an indication of a potential space. It felt like a sigil, like it had some kind of magic in it. So, I traced it, and I’ve been incorporating it into the work this way, as a sigil to manifest potential spaces, imbued with the magic of my mother.

P.E.S: You’re not constantly looking backwards into the past and researching ‘foreign’ places. What contemporary culture has further informed your practice by providing you with humor or inspiration?

A.B: I recently cited an episode of Real Housewives of New York in my MFA thesis paper. And I go back and re-listen to the archive of the podcast Nymphowars constantly, because it makes me laugh harder than anything else, and it reminds me that you can build a weird world out of any little thing.

P.E.S: You will soon be in Miami for an artist residency, which is the closest you have been in physical proximity to your Cuban roots. Can you describe what you hope to achieve while you are there? At this time, are you looking to directly interact with the local Cuban American population and culture there or do you imagine there will be more observation and sourcing?

A.B: When I’m at Fountainhead I’m hoping to get really in touch with the actual land. I have a lot of ideas that require foraging plant life you can’t really find up here in New York, and Miami’s plant-life is far more similar to Cuba’s, so I’ll have more relevant leaves to pull and fruits to pluck. I’d like to hand-dye my canvases using some of that plant-life, and I’d also like to incorporate it in sculpture.

Miami is a sort of politically charged place for Cuban Americans, and I’m curious how it will manifest for me, considering I’ve never spent a long time there, and most of my family has lived in the New York area since coming to the states. But I do have some family down there, and I’m interested in having some conversations and digging into their stories, gathering more “lore” so to speak.

I’d like to talk to other queer Cuban Americans, and compare experiences. I’m curious to find hubs that are both queer and predominantly Latine, since they’re so rare up here. That intersection can sometimes be a really strange and isolating one to find yourself in. But I’m hoping that getting in touch with the community down there will help me to manifest new community in the world of my work, to imagine more dream spaces to get together and talk and cry and fight and dance.

Follow Amy Bravo on Instagram at @_amybravo_ and learn more about the Fountainhead and their mission here.