The Venice Biennale’s central exhibition, The Milk of Dreams, is a curatorial feat of strength. It delicately weaves poignant historical and timely contemporary narratives across two locations, the Central Pavilion of the Giardini and the Arsenale. Cecilia Alemani has faced the notoriously difficult task of curating the 59th International Art Exhibition during a global pandemic, taking this time of great uncertainty and turbulence as an opportunity for speculative fabulation and the imagining of new futures beyond the known. Through the work of over 200 global artists, the exhibition creates a boundaryless space outside the primacy of the White European Male, where fluid cyborg bodies, animal-human hybrids, morphing plant life, women, queer people and those besides the binary revel in symbiosis, kinship and collectively.

“The Milk of Dreams takes its title from a book by Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) in which the Surrealist artist describes a magical world where life is constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination. It is a world where everyone can change, be transformed, become something or someone else.”

Cecilia Alemani

On entering the Giardini’s Central Pavilion, one is faced with a looming great elephant, unnerving in its stillness and uncanny in its accuracy. The work, Elephant (1987) by Katharina Fritsch, effectively announces many central themes of the show – a destabilisation of the primacy of man, a fracturing of the illusionary barriers between ourselves and others (things/people/bodies/planets/times), and a breakdown of reality as we expect to experience it. Cast in polyester and finished with matte paint, this mythic creature sucks light from the room while conjuring traditions of matriarchy, fables of grandeur and tragic histories of colonialism. Indeed, when displayed in this location the piece probes at such legacies as it becomes a homage to “Toni”, an elephant imprisoned as a spectacle in the Giardini until the 1890s.

Once past the elephant, a world of colour and wonder awaits – German artist Rosemarie Trockel’s bright “Knitting pictures” envelop the walls, deceptive in their ideological complexity and textured intricacy. Energetic sculptures, new paintings and a sense of anticipation fill this first room. One is led beyond the white walls into a velvety golden-orange cavern, at once mysterious, rich and enticing. It is the first of the historical time capsules that punctuate the exhibition like secret cabinets of curiosity. Each revolve around a salient theme central to the discourses at play in the show, spinning a veritable web of contextual reference, and arming the viewer with necessary tools of investigation. These sections exist almost as a bibliography or explanatory indentation to the exhibition as a whole, enriching the viewer’s journey and enlivening the creative voices of the past which echo in and reverberate around the contemporary works on show.

This initial room, entitled The Witches Cradle, resonates closely with the exhibition title drawn from Leonora Carrington, with works by her ideological contemporaries including Ithell Colquhoun, Claude Cahun, Meret Oppenheim and Leona Delcourt immortalised as Breton’s Nadja. This room is erotically charged with the poetics of the surreal and writhes with disobedient bodies in spaces between metamorphosis, the abject and the grotesque. Without a Fountain or a melting clock in sight and beyond the confines of Europe, we step alongside women such as Josephine Baker, Maya Deren and Lois Mailou Jones into the world of automatic writing, the subconscious and the sexually surreal. The work of Toyen caught my eye, her/their lithographs initially appeared like children’s book illustrations; however, on closer inspection, they are incredibly dark and twisted. In 1925, she/they moved to Paris and began identifying as ‘Toyen’, a derivative of the French for citizen, and dressed in both masculine and feminine clothing. The artists in this selection were pioneers of ideas central to The Milk of Dreams, they anticipated theories of the posthuman, ecofeminism, non-gendered and post-gender identity, female emancipation and transhumanism.

It is followed by another of the five time-capsules entitled Corpse Orbite, which harks back to the 38th edition in 1978 when Mirelle Bentivoglio displayed a primacy of women’s artwork exploring concrete poetry. This section features the work of 19th and 20th century artists who employ writing practices and personal languages within their work. I’ll admit, I found it slightly boring and was feeling a little visually overwhelmed and without the mental space for contemplative reading. This being said, Sister Gertrude Morgan’s wacky and wonderful paintings stood out to me immediately. A self-taught artist and devout Southern Baptist who turned to art after a series of divine revelations. She left her earthly husband in 1934, believing herself to be the bride of Christ and created copious artworks translating biblical messages and drawing on her divine encounters and inspirations.

After a quick walk along the canal and a welcome break, one enters the Arsenale (likely after a long queue) and is once again faced with a sculpture of monumental proportions in the form of Simone Leigh’s Brick House (2019). The meditative bronze bust depicts a black woman whose body becomes a kind of architectural form – a home, a sanctuary, a vessel, a dwelling, a monument – and was originally displayed at the High Line in New York. It is worth seeking out more of her poignant sculpture at the American Pavilion in the Giardini.

Onwards and upwards, to the elegantly designed ode to vessels inspired by Ursula Le Guin’s 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction which repositions the act of gathering as a primary technology in the evolution of humanity. It resists the masculine sword and spear, and in its place is a container. This arresting segment brings together works which explore the notion of a receptacle in an expanded sense – looking to the womb, the jug, the bag, and the body. In many ways, it becomes a kind of metaphor for the notion of an exhibition, in particular this exhibition, which gathers together certain artful objects with care and consideration and, in doing so, rewrites narratives and excavates forgotten or suppressed histories.

Noteworthy among the Arsenale’s works is Delcy Morelos’ Earthly Paradise (2022), a maze of mud and soil infused with hay, cassava flour, cacao powder and spices. It’s visceral and visually austere yet sensorially enticing; its scent and dampness overpowering and physically centring. Once again mythologies and traditions from beyond the false confines of the ‘western art’ remit take priority, with the work being informed by Andean and Amazonian Amerindian cosmologies and foregrounding the notion of interconnectedness. It postulates man as earthly being, grounding us within the dirt from whence we came and rejecting nature as inert, passive and under man’s dominion.

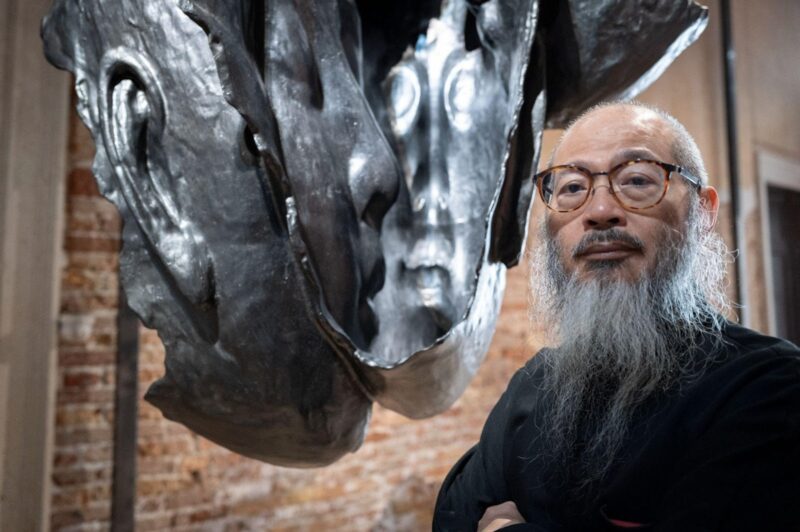

Thematically similar, Brazilian artist Solange Pessoa’s engulfing series of harshly monochromatic paintings Sonhiferas (2020-2021), depict animals, insects and creatures trapped in processes of metamorphosis. Like a primordial hoard, the organisms pulsate, squirm and slither within the canvas. They draw on her personal connections with the local landscape in south-eastern Brazil and meld the body, man and nature.

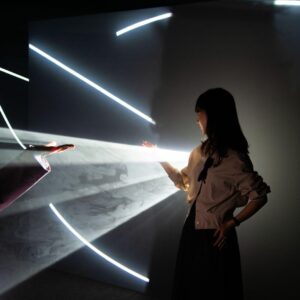

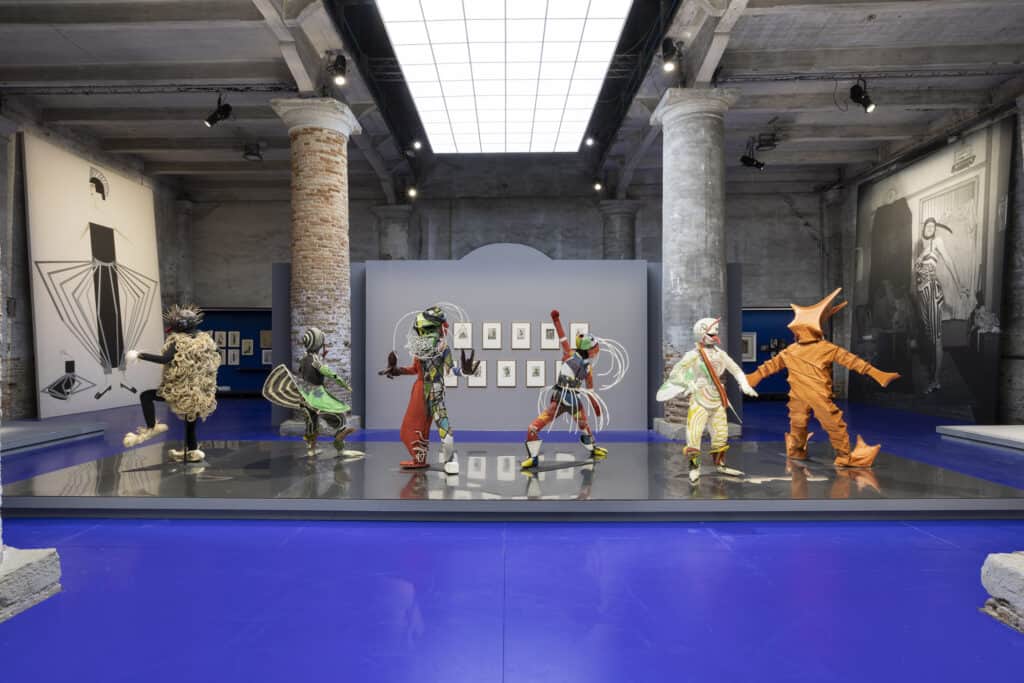

Plunging us into the techno-present/future is The Seduction of the Cyborg, the last of the five mini-exhibitions within the show. With cobalt blue walls and floor, this room is commanding and demanding, it presents us with all sorts of posthuman, postgender, posteveything assemblages that engage with subjectivities that are decidedly modern and possibly emancipatory. Drawing on writings by Donna Haraway, bodies in this space are sites of perpetual change and do not ever rest soundly on divisive boundaries or dichotomies. These beings straddle categories and codifications, pushing past barriers in every direction. Works by Louise Nevelson, subject of a solo-show in Venice, and Dadaist Sophie Taeuber-Arp stand out.

Other works in the Arsenale worth mentioning are paintings by Canadian born UK based painter Allison Katz. A woman of wit and wordplay, her paintings are rarely as they initially seem. The depiction of two octopus holding hands is tender and endearingly humorous.

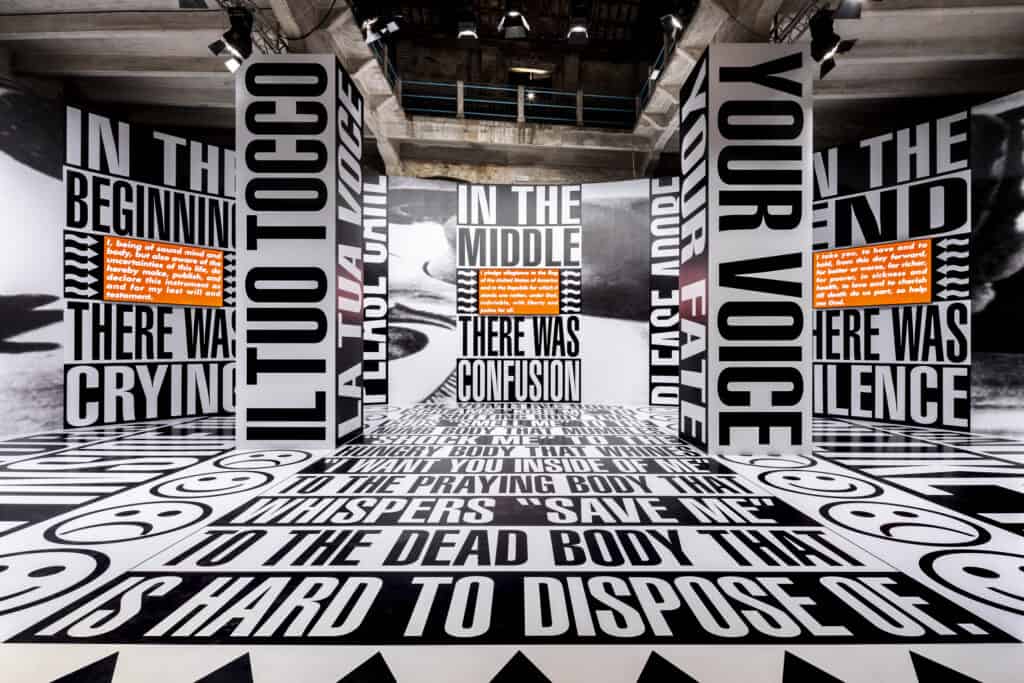

Another of my favourite female artists, Barbara Kruger has created a monumental installation of text, video and vinyl. Its bold scale and visual synchronicity are satisfying, while the message it holds echoes loudly through the hallowed halls of the Arsenale.

At this stage, you are gladly reaching the end of this artistic voyage of discovery and are likely mind boggled and a little saturated…but hold on a little longer. For me, the most memorable, emotional, stunning and affecting work comes along near the end in the form of Precious Okoyomon’s To See the Earth before the End of the World (2022). A beautifully intricate gardenlike installation that belies a complex history of entrapment, enslavement, colonialism and ecological destruction. You enter a darkened, fragrant room of soil, textile figurative sculptures, small running rivers and living plants. The kudzu plant populates the mini landscape, a prolific vine native to Asia that was first introduced to the US by the government as a means to fortify erosion of local soil degraded by the over-cultivation of cotton. Sugar cane is also growing within the installation, thus bringing together a selection of politically charged plant-matter which hold rich and devastating histories. The installation will grow, evolve and mutate during the exhibition’s duration, offering a re-enactment of the way in which kudzu proved uncontrollable for the US government. This living work offers numerous entry points and invokes a complex political past and present, drawing our attention to forces of power and control which have so often led to disaster. As nature grows and the art piece determines its own future, the artist herself revokes domination and the plant life speaks for itself.