Marika Thunder is a New York City-born and based artist who is known for her bright sense of style and unapologetic curiosity into the contemporary history of social culture. From the early age of her recognition, Thunder has taken direct reference from her childhood to reflect on the popular culture that she gravitated towards and now revisits as an adult woman. As many of us flocked towards different early 2000s trends, flavors, and scenes, and abandoned them just as quickly, Thunder, now in her twenties, further investigates the developmental phase of a child’s vivid imagination and the integration of pop culture, which shaped her interests in Hollywood paparazzi’s portrayal of celebrities, the flora and fauna of the American landscape, science fiction anime, high fashion, Pop music, and social media consumption.

Cotillion marks Thunder’s first west coast solo exhibition and is currently on view at de boer gallery in Los Angeles. The exhibition is on the heels of her second east coast solo exhibition in New York City at Public Access in 2021 entitled Dress Up My Lindsay. The ten paintings that made up Dress Up My Lindsay were direct references to collages from what Thunder called ‘The Red Book,’ a scrapbook of imaginative inspiration that she created and held on to from when she was nine years old.

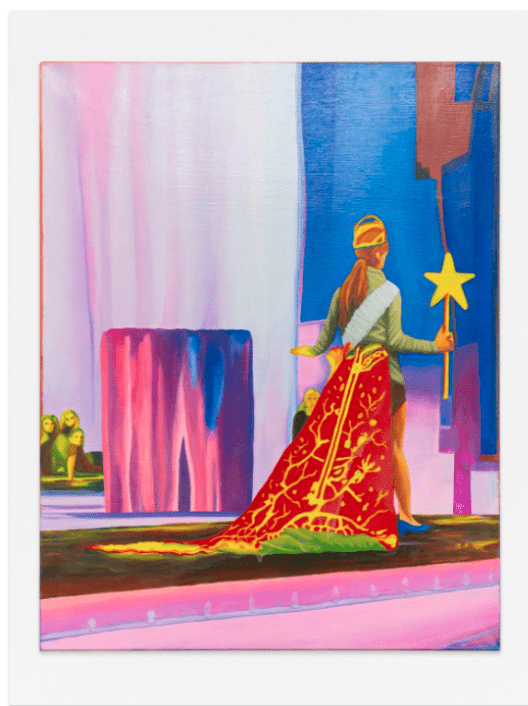

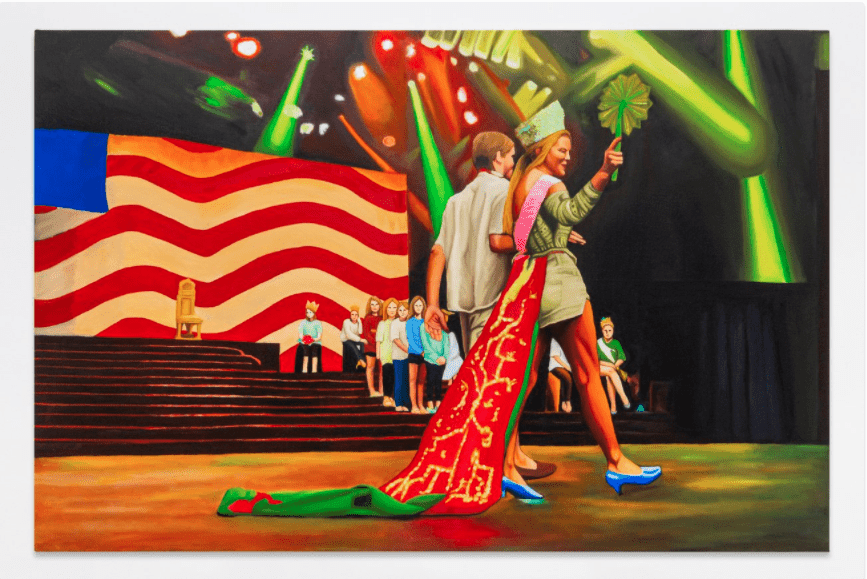

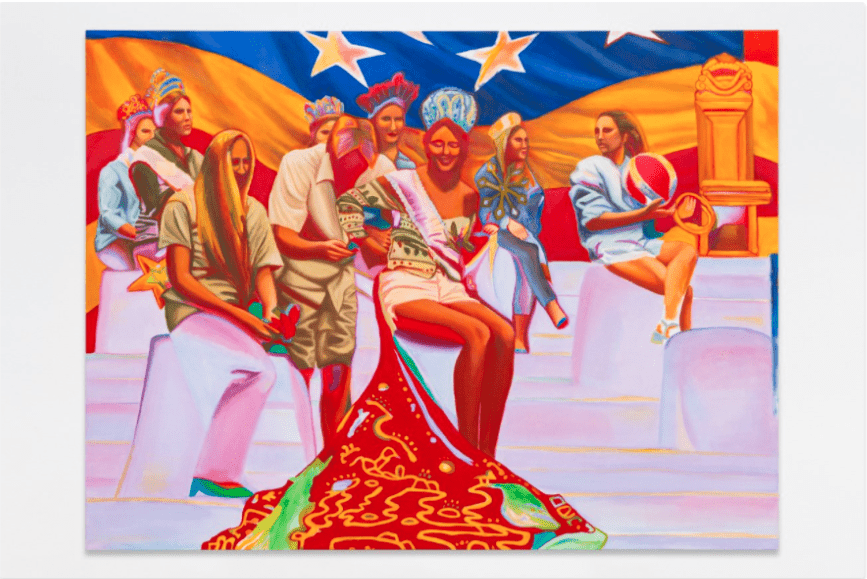

The exhibition at de boer gallery features seven oil paintings that highlight the classed and rigid (binary) gendered traditions of etiquette and societal expectation on young women and men that feature various intimate actions, through the very public presentation, of cotillion pageantry.

Cotillion comes out of the tradition of high-class 18-century English and American formal dances and balls, where young debutantes would be presented to ‘society’ with the goal of being paired off with a possible suitor. The Cotillion Dance was the “appropriate” way to end a ball, which is like what many Americans have encountered at a middle school dance and gym class, the square dance.

Cotillion has since then slightly restructured and evolved into months of classes, which are highly popular in Southern states of America, that not only train adolescence on the classic dance moves but etiquettes such as table manners and formal greetings that promise to teach those students how to act and participate as ‘respected members of society in social situations.

Q: Can you describe where you were when you discovered cotillion and how it informed your interest?

I was first introduced to cotillion at 16 years old when my grandmother asked me to participate in it because she thought it would be “appropriate”. I didn’t want to do it personally, but I knew it would make my grandmother happy, so I did. I was living in Corpus Christi, Texas at the time because I briefly moved there from New York City at 14 years old. I didn’t become interested in it until a little over a year ago when I found the photos.

Q: Can you talk about the source material for creating these works?

So, the source material is derived from photographs that were taken of the dress rehearsal for the cotillion ceremony. My mother visited Texas from New York and took these pictures on a digital camera. I completely forgot about them, but when I came across them, I thought they were so funny, and really embodied what I thought was the peak of the Southern Americana aesthetic.

When printing the photos, the printer happened to be low on ink, and the colors came out crazy and distorted. I then intentionally printed out the cotillion photos when the printer was low on ink. However, some of the original photos already had such complex and interesting color schemes from the stage lighting, that they necessarily need distortion from the printer.

As I was painting them though the color choices became a lot more intuitive as I learned to listen to the painting and engage in a dialogue with it during the process.

Q: So why do you think it became so important for you to pursue depicting this moment of time?

When looking back on these images taken of the event, I couldn’t fully recollect living through it, the whole thing felt foreign to me. There are certain periods of my life that I don’t even feel were my own experiences or memories. I felt like this collection of images had become a story on their own, a ‘mythological corpus’ so to say. I feel that these images speak on wider societal dynamics such as gender roles, classism, and the institutions we put children into. That was something I really wanted to investigate.

Q: At the time did you find these rituals of gathering and display to be empowering or destructive for you and those who were involved?

I’m not sure if it was “destructive” to me, but it felt very unaligned with my developing identity. For some of the girls there I’m sure it felt empowering. Cotillion is a very traditional ceremony and the young girls who were raised very traditionally to respect the values of a specific American etiquette probably grew up looking forward to this experience. I’m sure to some of them walking across a stage in a crown made them feel like a princess. As a little girl, I never related to princesses or Disney. I was a “tomboy” in that regard, I wore boy clothes and stuff for a bit, but more than that I was really into animals, and related to the animal kingdom more than human society.

Like most children, I struggled to integrate my imagination with the real world. Maybe that’s why I became rebellious as a teenager! I didn’t necessarily dislike the structures of human society, but I just didn’t see myself fitting in with them. But to answer the question, I do find rituals that indoctrinate adolescents or children to behave a certain way to be congratulated as destructive. I think it kills imagination.

Q: Did any of these character lessons and codes of conduct that were pressed on you leave an impression?

I can’t say they did to be honest, ha-ha! I’ve personally never had to go through the etiquette courses that the other girls did. I believe that something that you did if you followed through with the cotillion program, I just stood in the back of the stage. The girls that walk across the stage did etiquette training a year before. I was a mere observer compared to most of them.

Q: Why have you chosen to revisit these images from your childhood now?

My Dress Up My Lindsey exhibition was more focused on childhood because I found a scrapbook I made as a child of collages and used them as a reference for my paintings.

This series does involve me looking back at a period of my life, but I’m looking at it from a wider angle that wasn’t as much focused on age, but rather the cultural differences between the ideals of female beauty, etiquette, and expectations, based on where you live and are raised. Especially how it affects their development into adulthood and the inner monologue it creates within them.

Q: Your work is largely autobiographical, you’re even featured in one of the paintings, but on the other hand, it’s not about you. Can you elaborate on your interest in power structures and the vulnerable people who constantly have spotlights directed on them?

I have a bit of a background in acting myself but to be honest I found it to be such an incredibly taxing art form emotionally, that I decided to step back because maybe I wasn’t cut out for it the way I was with painting. Painting and other visual arts are taxing as well, but you’re with yourself and you don’t have to depend on other players.

Even though I’ve always been very social, growing up I excelled in individual sports such as swimming, MMA, and running. Believe it or not, I was a very sporty kid and while that lifestyle had many aesthetic differences- there were many similarities in the sense that it requires an insane amount of discipline, determination, and serious commitment to the lifestyle. I have a bit of an obsessive personality type, so art and sports were the outlets I could find that trait rewarded and gratified in.

However, I do want to address the power dynamics involved because that’s a really interesting point. Any kind of organized institution has an inevitable leader, and even in collaborative settings, to see how primal instincts can take over no matter how much people try to repress them.

Cotillion is a very repressed event in that regard, and while the spotlight is something that makes people vulnerable, part of the whole “training” and etiquette courses in cotillion is learning to perform in those circumstances. To not show vulnerability under the spotlight and to exude confidence. That confidence is derived from knowing you’re in power, financial power mostly, but also physical power from successfully conforming to beauty standards-conservative American beauty standards. It’s a rather limited palette and therefore requires a lot of repression and ignorance.

Q: Some faces within these paintings have an undefined and insecure look while others have a very expressive quality of self-assurance and pride which is mostly assigned to be those at center stage. In your observation and experience, how can ‘center stage’ affect young adolescents who are in many ways still growing?

I think adolescents, and I’m saying this from personal experience too, are constantly seeking the approval of others. I believe it’s a way of confirming and reinforcing one’s identity through the validation of others. I know this is especially true in places where conventional value systems are upheld, and conformity is necessary to be accepted. Aside from all that though, many young women long for the “spotlight” to be put on them because they’re taught and conditioned to curate an exterior that can receive as much of a positive reaction as possible.

The expressions on the Faces in the painting were more so reflective of how I felt during the whole thing. I think it is a common trait among many figurative painters to place oneself inside their work, whether it’s intentional or not.

Q: In your paintings, you’ve chosen to use distorted but vibrant filtered colors from the photographs to depict the figures and their environment. That paint looks as if it’s radiating and provides a further emphasis on the motion of those who are in tow, curtsying, and waving. Why was it so important to capture these figures while in motion?

The motion symbolizes many things. The distortion from it is meant to convey the elusive nature of recollecting memories and their fragmentation. The whole event itself was very dynamic though from the rehearsed movements such as curtsying, waving, and escorting across the stage. These movements are long-established feminine gestures that are taught in the cotillion etiquette courses to serve as signals of class and femininity.

I think it’s funny to have that very classically trained and slightly repressed type of movement occurring at the same time as the frantic energy that is present in a room full of hormonal teenagers and rehearsal expectations. And American culture’s fascination with exhibiting/putting children on stage, possibly because it’s a way for adults to vicariously live through them and revisit their unfulfilled childhood imagination.

Q: As an adult woman now revisiting childhood idolizations and experiences, at first with Dress Up My Lindsay and now with Cotillion there is a continuing conversation of ‘dress up’, coming of age, societal pressures, and innocence. Are there institutions are you most interested in that are assisting and impeding on the growth of adolescents?

Ah, this is a great question; do you have all day? Ha-ha!

Something that I think about a lot nowadays is what I like to call the “war on imagination” or the “war on innocence.” My Lindsay Series has a lot to do with innocence, exploring my childhood innocence and imagination but through “dressing up” her.

Like so many child stars, I think Lindsay was robbed of her innocence at a young age because of the pop culture media’s exploitative nature, and as a society we watched her crumble from it. Through watching her difficulties growing-up we see the way the media as an institution exploits and targets children in a very conspicuous way.

This then begins to blur the line of observer and performer, because our observation and engagement has the media simultaneously targeting and exploiting us too. This is especially the case nowadays with social media where profit is generated through engagement.

I wanted to investigate how the imposed institutions such as school, healthcare, and even certain belief systems, are exploiting and conditioning us, from a young age, to conform to their standards of existence.

Cotillion was my way of expanding on that idea, but through painting an experience that I felt captured these dynamics of society in a very vibrant and sort of satirical way. I don’t want it to come across as all doom and gloom because I do think there’s something fascinating about it and seeing how sometimes structure can bring out the best in people.