Collezione Maramotti presents Ante mare et terras, the first solo exhibition in Italy by the New York-based, Croatian duo TARWUK (Bruno Pogacnik Tremow and Ivana Vukšic). Introducing four large-scale sculptures and a series of small drawings, the show explores how identity shapes and constantly moves through metamorphosis, memories and the subconscious.

The works are ‘like a riddle’, as Bruno told me at the Collezione. They are not a closed system but, instead, they create a continuous dialogue with the space, people, and time. They represent, indeed, a metamorphosis, a continuous cycle. ‘Viewers’, the artist added, ‘must bring their own space into the work. When you walk into the room you are triggered by the works’ presence but you are part of the work at the same time. With the mirror, this reaches its apex because you see your reflection and, at the same time, you see all the sculptures in that same space as well.’

Read my interview with TARWUK, where we investigate the idea of identity in its continuous metamorphosis, the importance of time and epiphanies, and the merged language that the duo immediately created as they started working together.

‘Ante Mare et Terras’ immediately transports the visitor into a strong, cohesive narrative. The sculptures exhibited create a powerful dialogue between each other. Do you think of your works as part of a cycle? Do they tell a story all together or can they act as separate entities?

The four sculptures presented at Collezione Maramotti form a group, or a cycle if you prefer. They are all connected by the idea of metamorphosis, a transformation of form. The title of the show comes from a line in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a poem from the 8 century AD marked by almost arbitrary changes of focus from one metamorphosis/transformation to the other; it has a logic of its own that is somewhat hard to follow. Our cycle of metamorphosis starts with Tuzni Rudar, the only sculpture from the group that we had exhibited before, at 15Orient gallery in NY. That sculpture, which includes a mirror, felt like a really important event in our practice; it opened up new possibilities to investigate in this medium. Each sculpture exists as a separate entity, and has formal solutions that are individual, but there is a common group of materials that they share.

Furthermore, each figure is frozen in a different moment of progression, or deterioration of the anthropomorphic form. They are suspended between growth and decay, as if they were in an only static point in the universe. So, at ‘Ante Mare et Terras’ the work depicts four stages of metamorphosis.

Your figures fuse together a series of thick layers, incorporating heterogeneous materials together. Time, practices and objects coexist in a surface which seems to be in continuous development. I believe this play between materials, semi-anthropomorphic shapes, and ‘objets trouvés’ creates a ‘punctum’. This, as Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida, is the ‘element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me.’ It is something which you cannot name or perceive with complete clarity. And, indeed, I feel as your sculptures were trapped in a constant dynamism, both physical and ideological. Will they keep changing? Are they finished? Will their material last forever? Are they moving or are they still? Organic or dead? Beautiful or monstrous? Do you ever think of your work this way?

In our practice objects are secondary. Words come at the far end of the creative process. Our main interest is in experimenting with Selfhood. We are two, but we work together with no division of labour, in a complete merge where the boundary between one and the other blurs and becomes porous. This allowed us to grow outside of the individual self. The works in the studio are like experiments in a laboratory, some take years to grow and become resolved. As we work on everything together, either at the same time or taking turns, the objects accumulate layers and materials, and are being taken apart, sanded, sawn in pieces and glued together again. We shift through the same dynamics of building up, revealing, decomposing and growing simultaneously. The heterogeneity of materials is not planned either, it grows organically and incorporates a wide array of found and salvaged objects from our environment, as well as our body residues.

Time is definitely another material that interests us a lot. Some sculptures sit in the studio for years without being touched at all. A sudden ray of light at a specific moment can lead to a completely new perception of a familiar shape, a new recognition that could make the sculpture finished. As we work really intuitively, it often takes time for us to grow and catch up with our unconscious self. Often, we’ll make something which we’re not able to understand, we archive it. Then, after a long period of time, while usually working on something else, a strong feeling of epiphany will overcome us, as some sort of recognition of purpose. This way, the work finds its place from the archive bin in the studio rotation again. When trying to figure out what constitutes an individual and where one ends and another begins, duality seems to be a principle we come to over and over again. But we want to look behind it as we’re trying to imagine something that exists outside of language, something unimaginable.

As you already noted, Tuzni Rudar, the central figure, is punctuated by a mirror which activates the spectator by showing their reflection in the work, while also incorporating the other sculptures in the reflective surface. Is there a psychoanalytical reflection in this mirror? How do you use it?

15Orient gallery in NY, the location where that sculpture was first shown, had a mirror above the fireplace. We conceived it as a response to the architectural element, the mantle with a mirror, that already existed in the space. It was interesting to create a situation where the viewer is confronted with a sculpture where, in order to see its front, you have to see yourself in the mirror as well. This way, the mirror not only doubles the sculpture, but it also connects both the viewer and the sculpture into a new reality. When making the sculptures, our main focus is on emotions – the intuitive process without a preconceived method or system. We never make sketches. Once we both feel the object is complete, we start thinking about its experience in the space. We’re very much interested in architecture, in addressing every exhibition according to the specifics of the site. Certain kind of theatricality is closely tied to the act of exhibiting the work; the architecture that hosts ‘the play’ is key.

Exploring identity, you use the ideas of metamorphosis, memories and subconscious tensions to guide you. Identity is a very complex and fragile subject; it develops and acts both individually and socially. How much of your personal self and experience ends up in the final work? How much is it open and universal, instead?

When we started working together, it was immediately obvious to us that we would not use our individual names as authors. TARWUK was both Bruno and Ivana, but it was also more than that. We thought of TARWUK not as a duo, but as a third entity that is neither or, but both at the same time. As time passed, we started thinking of TARWUK as a condition under which we exist, which we inhabit. Language and society form individuals and, in turn, individuals reshape language and society. TARWUK represents the situation we live in. This also becomes a subject of change and transformation as we exist in the society and language. In that way, every personal experience we bring to TARWUK, or share under it, affects the process. And as we are inseparable from our subjectivity, that individual subjectivity is also something we share with others. The personal has a potential to connect with the universal.

Do you think of your works as cathartic or hopeless? They are monstrous and beautiful at the same time, as it is perfectly epitomised by Tužni Rudar in its juxtaposition of steel chains and bright roses.

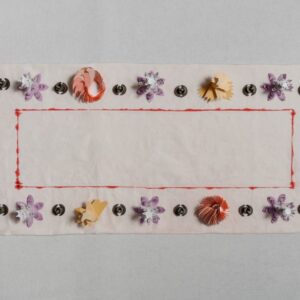

The process of making these works is rewarding for us, it liberates us from the tyranny of ego. This approach results in a specific aesthetic where layers of material are inevitably added, scraped off, cut, glued together, recombined again, sometimes even completely discarded and destroyed. What interests us is incorporating materials from our immediate surroundings, our daily life, into our works. There is also a curiosity towards how something becomes a charged object. How can a random thing be infused with energy and transfer that to the viewer? Flowers perfectly exemplify how beauty is absolute. Even when they change from an extraordinary wonder of nature into a wilted heap they never stray from the beauty, since they never stray from the mystery of life.

What pushed you to have some of your sculptures trapped in a space? Tužni Rudar is tied to the room by four mild-iron wires, KLOSKLAS_?rgNAWSS.143 wants to walk but is blocked by the wall, a sort of rope/chain returns in KLOSKLAS_55NeoNoch as well. How do you feel about this sort of impossibility to move?

For us, the sculptures exist within the space. The footprint of the sculpture would be the minimum amount of space it needs to exist. Each sculpture claims space within the architectural parameters of the exhibition room. Architecture is a container for staging an exhibition; it gives context to the work. To us, it becomes a malleable element that we can manipulate and transform.

All four of these sculptures are addressing the architecture in a different way. None of them are directly touching the floor, and two of them have a direct interaction with the vertical walls of the room. In a way, all of them have a parameter within which they exist, which contains them in their entirety. So, they bring their own space to the exhibition arena. Time is what connects these four works together. Here, we are investigating how to show the passage of time in an object that is seemingly static. Since time does not exist outside the space, by investigating a process of metamorphoses we confine time into each sculpture. By placing sculptures in a circular arrangement, we also circumscribe it in the exhibition room.

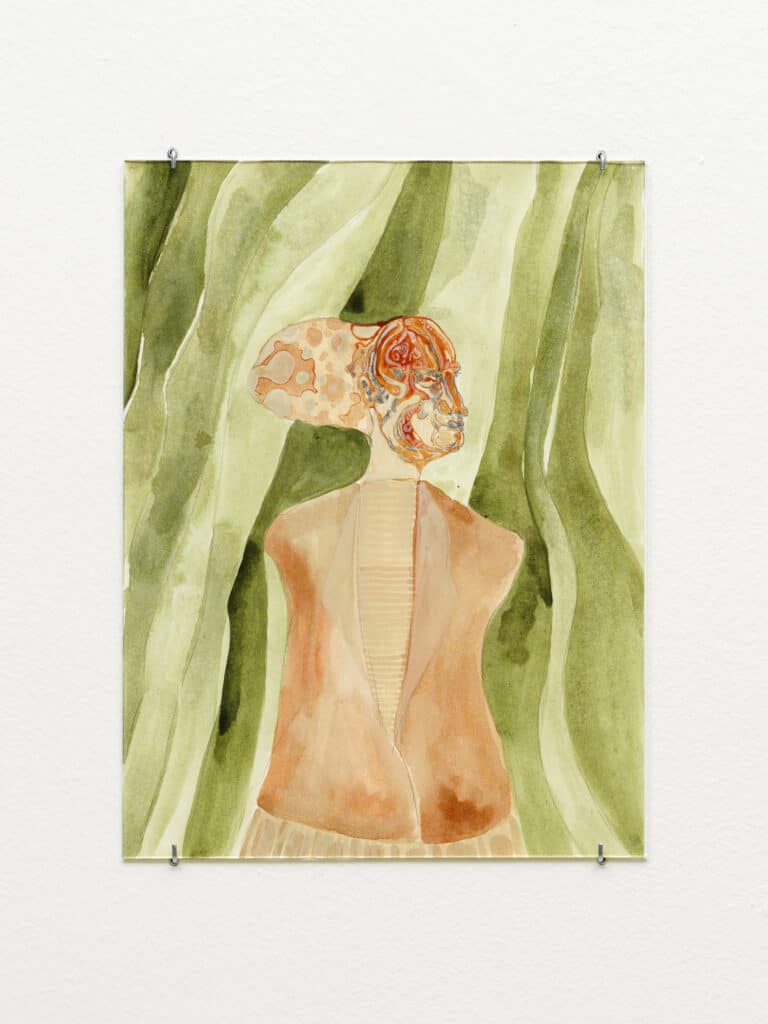

At Collezione Maramotti you also presented a body of drawings. What role do they play in your practice?

Drawing is something we constantly and compulsively do. We either work on the same drawing simultaneously, or we pass these back and forth between us. We mostly use graphite, coloured pencils and watercolours. The drawings are not sketches for paintings or sculptures, they exist in their own right. We made the group of drawings presented at Collezione Maramotti during the first year of the pandemic, when we lost access to the studio we inhabited at that time. Various friends hosted us in their studios. During a seven month period we moved five times. We had to adapt the way we make art to the circumstances that surrounded us. Drawings this size we could make no matter where we landed and they were a good way to make the temporary space our own in a short amount of time. We presented 12 drawings here that capture a year of our life.