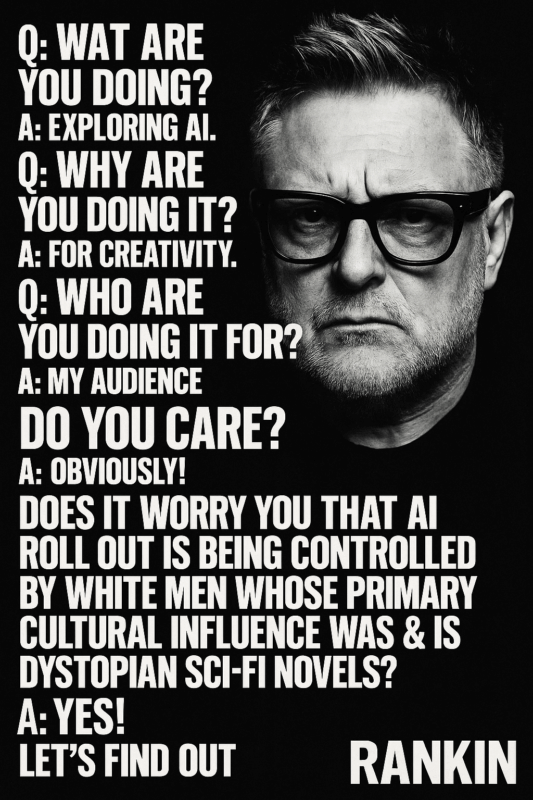

I caught up with Rankin recently the well know photographer and filmmaker, to talk about death. His agency has produced two pieces of creative work to help people talk, learn and deal with death, the most recent being a book.

Mark Westall: Is it just a book or is it more than just a book?

Rankin: Oh God, man, yes. This is like 15 years in the making.

Oh, I see, I thought it was just part of a campaign for Royal London.

Royal London, yes. We started working with them back in February last year, pre-pandemic. They understand the fact that financial planning and the purpose of life are quite in tune with each other. Their marketing director said to me, “We’ve got some purpose work we’d like to do.”

Royal London was set up as a company to put money away for your death originally. I was like, “Oh, there’s a really great parallel between now and then.” They do a lot of charitable work around that. I don’t know if you know, but, I can never remember the percentages, but there are a lot of people– In fact, I’ve got one on my Nextdoor app the other day, where people can’t afford a funeral because funerals cost £5,000 to £10,000 or more.

There’s a lot of funeral poverty in Britain and sometimes the council has to pay for it. But if the council pays for it there are all these rules including sometimes that you are not allowed to go. There’s a lot of politics around it. I said, look, there’s a really interesting taboo about death. People don’t like to talk about it, and it means that people don’t necessarily save for it or worry about it or think about it.

I said it would be really good to do a project around that and that project concept came from my personal experience, my parents died 15 years ago. When they passed away, I was so unprepared for what happened and how it felt and the loss and the grief and the emotional difficulties that I had. Also the practical side of it all like funeral planning and stuff, we’d never talked about any of it. What I said to Royal London was, I’ve done three or four projects on dying in the last 15 years and I’ve become more and more in tune with being able to talk about it.

I said I think there’s a really big project in a book on how to die well. There’s millions of books on having new babies, but there’s very few books on dying. I said if you want to do something that’s actually beneficial to society, you could do this and you can go through all of the different elements of it from grief to financial planning, where you’re actually being useful.

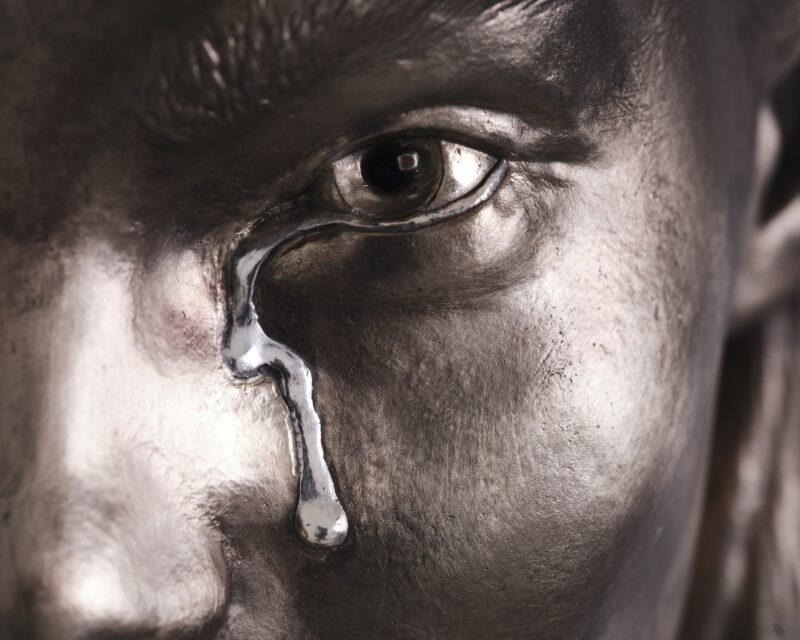

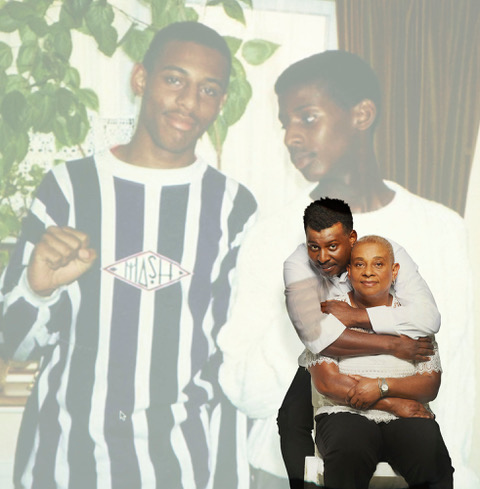

We started off with a grief project called Lost for Words and that was an online exhibition, where I photographed people that had lost people. We just talked about grief and how we don’t talk about it. That, then, set up doing the book so it was a really nice transition between the Lost for Words grief project to the How to Die Well book. The How to Die Well book was a culmination and all of the research we’d done.

I put a great team together to produce the book from our content division. They did the research and talked to experts about it etc.

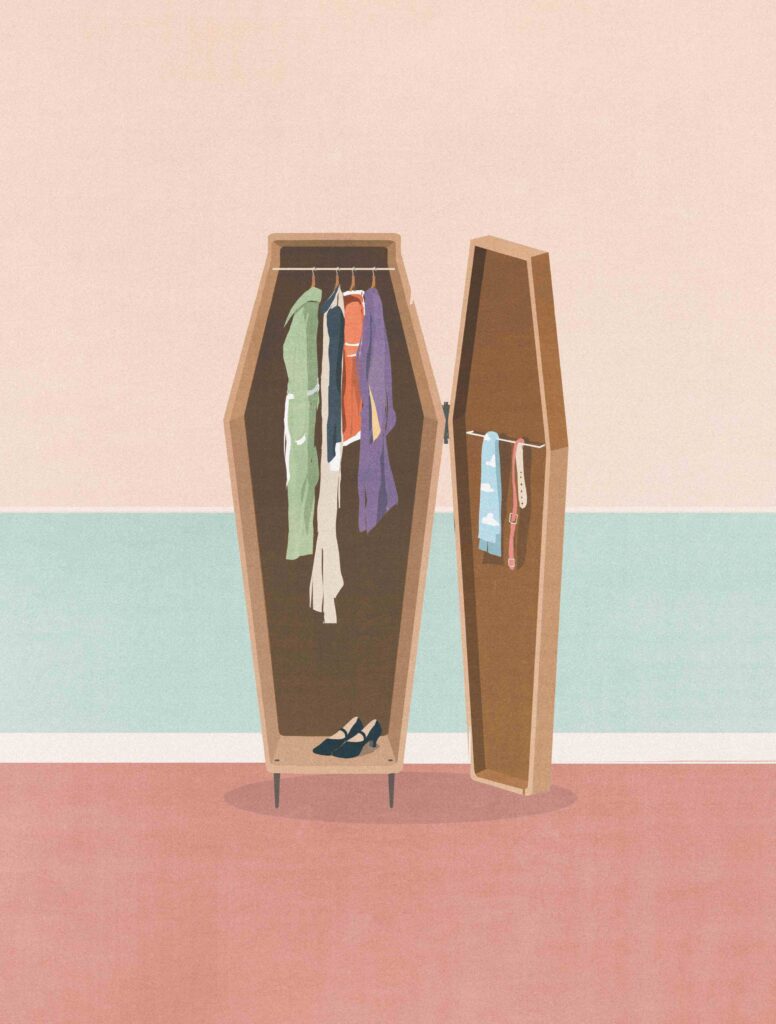

It’s got some amazing illustrations by Andrea Ucini in it. It’s got no agenda in it, you know what I mean? It’s not trying to be religious, it’s not trying to be political. It’s just, this is it – a guide. If you want a guide, this is a good guide. From start to finish, you’re going to have a positive experience of it. Literally, if you get a terminal illness, a family member is getting older, if you get this book, and it’s free, you can download it as a PDF, if you get it just have a look at it because it’s just so practical and it’s such a brilliant, useful tool.

I just wish I’d had it. Really, for me, it’s like the circle has been completed. Obviously, as a photographer, we’re obsessed by death because time is such a big element to what you do as a photographer. Death is there, it’s on your shoulder all the time. Is this image going to live on forever? I’ve been really obsessed with flowers and how, as they die, they become more beautiful in a way and decaying and, also, getting older, starting to think about it in a different way. The project, as a whole, over the last 15 years, I’ve gone from being very, very scared of talking about death to being quite relaxed about it

In a lot of places people celebrate the person’s life rather than mourn their death don’t they?

In many communities– They’re all different and we cover that in the book but it’s a very Protestant, British, Victorian taboo thing that we don’t really know why we’ve got a problem with it. Even Catholicism’s gotten a bit more, it seems to be a little bit more in touch with it. I don’t know, we’d call it Presbyterian in Scotland, but it’s a rigid, Victorian perspective.

Don’t cry.

Yes, it’s really strange. Even Victorians had a little more– The other thing is that what has happened with death that a lot of people don’t realize is it has been anesthetized. It’s been separated. Before the first World War, death was very much a part of life. When you died, the person that had passed away would probably stay in the house, you would say goodbye to them, it was protracted, whereas now– I remember when my dad had a heart attack, he went through the doors, my mum, my sister, my son, and my kid, my child, at the time, were there on the other side. I was behind the door and they were on the other side of the door and my dad was dying. I was like, “Do you want them to come in?” My and my dad was like, “No, I don’t want them to see me like this.” I can’t even remember if they went in to see him. It was like he was gone. I got to say goodbye. I got to hold his hand as he died. I got to hold his hands. It was really weird. I hadn’t thought about that for a while. I got to hold his hand and to say goodbye to him. I thought, “I got to say goodbye.” Essentially, I got to say goodbye, right?

That was really important and if you don’t get that, it’s really not a positive experience.

How old were you?

Oh, God, I was 40. I was 39. I was 39 just about to turn 40 so it was pretty heavy, actually, but weirdly, I can talk about it now.

What’s the one thing you would recommend?

The thing I always recommend, and this is what I’d recommend to anybody, is record it. Literally, turn yourself into an interviewer. If you can film it, film it. Just have those conversations. The one thing that I regret the most is not having those conversations. I just wish I’d had recordings that I could go to just to remember them. I see my parents in dreams and it’s such an amazing thing to see them again and to have those moments with them, but I really regret not having had those difficult conversations, and just having it all recorded. Almost like, how do they want to be remembered and how do I want to remember them. What do I want to– It’s weird even after 15 years. I sometimes wake up and think, “I’ll call my dad,” and I can’t. My parents, in a way they made it easy for us because they’re not non-religious. They were like, “Look, once we’re gone we’re gone,” so they made that pre-death bit quite easy, but the post death, it was like, “I really wish they hadn’t made it easy.” I was like, “I wish we’d had those conversations. I wish we’d–“

Are there hard copies?

Yes, yes. I can give you one.

People can get them easily?

Yes, yes, yes. They’re good. It’s a really good book. I mean, I’m not saying that because– I would definitely use it.

This subject I presume it is completed. Is there more for you to do?

It’s like I feel like we’ve completed it completely. I feel like we’ve done it and it’s really good. It’s a really good thing end product. Yes, it is a marketing campaign but it is what marketing campaigns should be – really useful that will be useful for the next 10 to 20 years. I’m really proud of it because it does everything that I wanted it to do whilst also being really good for the brand.

It would be good if brands did more stuff like this.

This is, literally, what we set up our agency to do, things that were good for the human condition. That are also really good for the brand. That’s the sweet spot for me.

I think that’s what people demand now

Yes, they demand it which is great, they hold their brands to account, they demand truth and authenticity and that’s what we aim to achieve with the work we produce.

You can borrow How To Die Well A Practical Guide to Death, Dying and Loss from public libraries and download a free PDF copy HERE .