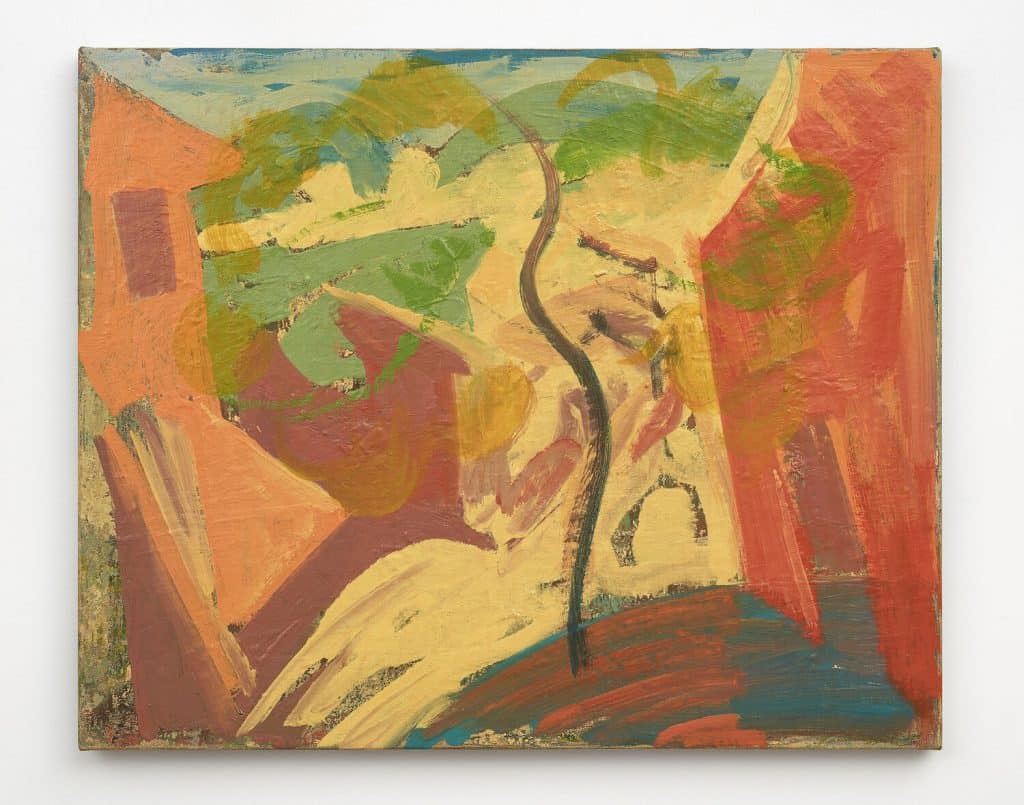

Tim Stoner, Edge of Town (Santa Barbara), 2016-18. Oil on linen. 61 x 76 cm Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London.

Live now an online Presentation exploring the southern Spanish town of Ronda and its influence on various British painters since the 19th Century.

It has long been a perfect location for artists wanting to define nature’s fundamental dynamism, which is reflected in our inclusion of work by David Bomberg (1890 – 1957) and Tim Stoner (b.1970), both residents of Ronda in different times.

Ronda has natural grandeur. Perched high up in the Andalucian mountains, the town is sliced in two by a gorge that drops four hundred feet. Historically Ronda has attracted many friends. First settled by the Celts, following brief Roman rule there was Islamic domination before Catholic Monarchs recaptured the area in the 15th Century. The prehistoric caves of La Pileta still exist with their primitive drawings (pictured), some 40,000 years old.

The fabric of Ronda is rich and tormented, but it is a region where past and present are inseparably connected. The current use of the irrigation systems date back to Islamic times, and there is still an almost pagan religious fervour present at certain times of the year.

Various important artists have been residents of Ronda. Ernest Hemingway and Orson Welles spent many summers here writing, and German poet Rainer Maria Rilke kept a permanent room in a local hotel. British artists, as early as David Roberts (1796 – 1864) and later William Strang (1859 – 1921) settled in Ronda, taking in the landscape.

David Bomberg (1890 – 1957) and wife Lilian Holt lived in the Spanish mountain town from 1934 to 1935 and then again in 1956 until just before Bomberg’s death in 1957. His good friend and once student at the Borough Polytechnic, Miles Richmond (1922 – 2008), was also active in Ronda, keeping a studio there. Bomberg described Ronda as ‘the most interesting of the towns of Southern Spain’, and for good reason. The history Bomberg inherited when arriving, through the British artists Roberts and Strang, was not of particular interest to him. The paintings they made were sedate, representational considerations of an interesting landscape and lack a particular mystery.

It is really only until Bomberg arrived in 1934 that the seismic potential of the area on painting was felt. The landscape here was a big influence on his practice and approach to painting in general. In Ronda, ‘Bomberg finally learned how to convey his subjective experience of mass in all its fullness’ (Cork, p.32). During his time there and after, his work became more charged and violent, as he grappled with an area historically and geologically unsettled. Bomberg excavated the landscape’s explosive potential.

This same shift in approach to painting is felt by British artist Tim Stoner (b. 1970), who has been living on and off in the town of Ronda for the best part of 15 years. Incidentally, Stoner and Bomberg share something common; they both grew up in London’s East End and both found fertile atmosphere in Ronda to get stuck in to painting. The psychology of the area seems to have crept into Stoner’s work, too, as when he arrived in Ronda, he “began speculatively tossing unfinished canvases in swimming pools, pouring dissolving chemicals on their surfaces, and, decisively, assaulting them with palette knives”.

As in ‘Edge of Town (Ronda)’, 2016-18, depicts the same vantage point from which Bomberg made a number of works, unbeknownst to Stoner when making his. One goes off the main high street, up a hill and a right turn; the whole scene ends and there is a startling view into the New Town. In Bomberg’s ‘The City, Ronda, Spain’, 1935, he opts for a more obvious calculation of the tops of the houses and trees, suggesting the denseness and friction of the area. It is a zoomed in perspective of Stoner’s ‘Edge of Town (Ronda)’, both having in common depicting the house on the right. In Stoner’s work, perhaps at dusk, the light is depicted with extreme handling of colour, as it falls behind the horizon line and dances among the marks of the sides and tops of houses. Bomberg’s suggestion of light is done in opposite; by using his finger to rub away colour, and revealing the paper beneath.

It seems the challenge of painting the area is to really find the essentiality of the area through the painting. ‘Edge of Town (Santa Barbara)’, also painted at the same spot, exemplifies this essentiality through the reduction of form into larger brushstrokes and lines. The painting is fiery and charged; it contains the mystery of the area within, the feeling as the ashes just begin to fall.

Stoner’s works from Ronda are subconscious testimonies of everything he has digested from the area since he arrived. With a light and respectful touch, his paintings reflect the layered and disparate history of cultural and religious influences exerted on the region over centuries. More figurative works, like Olive (Ronda), 2018, (Stoner’s worst enemy is olive tree pollen), and El Parque, 2017, remind us that people still walk the streets of Ronda. These show a different kind of engagement with Ronda; through its inhabitants. But always with Stoner’s Ronda works, he mines into the landscape and how people fit in with the convulsive geological stress of Ronda. Ronda belongs to itself, and the people borrow its force, as does Stoner, and as did Bomberg.

vardaxoglou.com/presentation-ronda-spain