“…the University will have to become one place, among others, where the attempt is made to think the social bond without recourse to a unifying idea, whether of culture or of the state. In the University, thought goes on alongside other thoughts, we think beside each other. But do we think together?

~ Bill Readings, The University in Ruins, 1996

‘Trellis: Public Art’ is a programme of knowledge exchange between researchers and artists in the East End.

Frames and frameworks

Usually associated with gardens, a trellis plays a functional role – it supports the growth of climbing plants – as well as an aesthetic one. As a framework, a trellis helps to direct growth in a way that facilitates gardening as (interspecies) co-production process. As a frame, the trellis directs the eye towards an aesthetic engagement with the garden as place or experience. Trellis is therefore an apt name for a multi-stage public engagement initiative that involves artists, researchers and participants across several east London communities coming together through diverse processes of creative collaboration. Trellis is about working together and working together can be complicated.

Trellis consists of five projects, each with its own processes and priorities, thematic interests and approach to collaboration. Together, these five projects have resulted in a multitude of artistic outputs – walks and workshops, films, drawings, photography, an artist’s book – as well as multiple legacies that may or may not be defined as art, including new relationships, new knowledge and understanding, new ways of working together and, more tangibly perhaps, tree cuttings that will soon be planted in the grounds of UCL East, the university’s new campus in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

The catalyst for Trellis is the construction of UCL East, part of the ongoing transformation of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. In addition to UCL, the site will see major cultural institutions including London College of Fashion, Sadler’s Wells and the V&A making up a cultural cluster known as East Bank. As a new arrival in a place undergoing significant change, UCL East is taking seriously its responsibilities to both new and existing communities. Multiple projects have been taking place in the local area ahead of the scheduled opening of the campus in 2022. This is where Trellis comes in: as “part of the wider vision for UCL Public Art and Community Engagement to create opportunities for collaboration between artists, researchers and communities based around the future UCL East campus”. In some ways, each artist is being asked to play a mediating role between the institution and local communities. But in doing this work through contemporary art, Trellis also opens up possibilities to stay with and attend to specific entangled complexities beyond the simplifying narratives of regeneration.

While each project can be considered alone and judged according to the criteria that it sets out for itself, there are nonetheless a number of connecting threads that might be woven together to help think about shared concerns or divergent strategies. The aim of this text is not so much to provide an exhaustive description of each project but to begin to map the connections between them.

For 2020-21, the five projects are:

1. Flow Unlocked, involving artists Jon Adams and Briony Campbell with autism researcher Georgia Pavlopoulou, working together with autistic communities to explore the vital importance of relationships for autistic people;

2. Xenia Citizen Science Project, consisting of artist Sarah Carne collaborating with biochemical engineer Charnett Chau and architect-designer Danielle Purkiss on a composting project with Xenia, a community knowledge and language exchange for women in Hackney;

3. Mulberry – Tree of Plenty with artists Sara Heywood and Jane Watt working with biomaterials specialist David Chau and Bethnal Green residents to explore the multiple meanings and material applications of the mulberry tree; 4. artist Edwin Mingard in partnership with interdisciplinary historian Keren Weitzberg and people in east London who have been oppressed by the hostile environment policies instituted by the UK Home Office; and

5. Light-Wave, a collaboration between artist Rubbena Aurangzeb-Tariq, sign language researcher Bencie Woll, and people in east London’s deaf community to engage with and increase recognition of their history, culture and language.

Mapping people and place

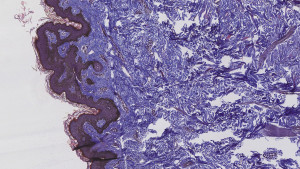

Both Light-Wave and Mulberry have been informed by an interest in mapping as a way to understand and visualise relationships between people and place. Heywood and Watt, who have worked together on several site-specific projects in the past, settled on the mulberry tree as a way of exploring overlaps between materiality and local history. Across walks, workshops, online talks, a short film and more, the pair, along with their collaborator, Chau, channelled multiple forms of knowledge, including local legends, biotechnology, oral history, memory and lived experience. There are two species of mulberry tree in the UK: most are black mulberries (Morus nigra) which produce a juicy, wine-like fruit, but there are also white mulberries, much rarer in the UK, which are grown for their leaves to feed silkworms. Heywood and Watt charted the appearance of these species in London from Roman times, their use in medicine, food and drink, and as symbols of official local identity (there are mulberries on the Tower Hamlets coat of arms and on local street signs) and even sites of resistance, such as the ancient mulberry tree threatened by developers and the ongoing battle to save it by local campaigners. According to the artists, Mulberry developed through the “organic growth of conversations from one person to another”. The project therefore did not only map existing connections but formed new ones through conversations and informal modes of knowledge exchange.

Multiple conversations have also created new connections through the work of Aurangzeb-Tariq. Perhaps best known for her expressive, allusive painting and drawing, Aurangzeb-Tariq makes work in response to her experiences as a deaf Muslim woman. After discussions with deaf people in east London, Aurangzeb-Tariq’s initial aim for Light-Wave was to create a collaboratively sculpted mosaic map that would use imagery based on Sign Language specific to east London to draw attention to sites of deaf historical significance across the area (such as England’s first school for deaf people, opened in 1783 off Mare Street in Hackney).

But with Covid-19 rendering this initial plan impossible, the project was reconfigured in response to numerous online video conversations around language, translation and the experience of relying upon interpretation. British Sign Language was recognised as the fourth language in the UK in 2003 but while Scotland passed a BSL Act in 2015 to promote its use, there remains no equivalent legislation in England despite sustained campaigning. Across 2020-21, conversations revolved around, among other things, Black Lives Matter. In Sign Language, Aurangzeb-Tariq tells me, there are different ways to sign “Black” (depending on whether it refers to a person or a colour) and no single sign for ‘Matter’. As researcher Bencie Woll puts it, “2020 saw the very rapid introduction of a new expression and the way somebody signs it can tell you about the attitude they might have’. These discussions therefore took place along lines of difference within the deaf community, lines of separation or connection based on age or politics or lived experience. In response to these important conversations, Aurangzeb-Tariq is producing a film that combines personal stories from deaf participants with a series of the artist’s recent time-lapse drawings of bodies expressing overlapping emotions and ideas through Sign Language. “I’m mapping out different communities through conversation,” she says.

Questions of language and (mis)translation inform Sarah Carne’s approach too. Like Heywood and Watt, Carne’s work has long engaged with materiality, but her interest is more in the relationship between materials and status, questioning why certain materials are privileged and valued and others derided. For Trellis, Carne, Chau and Purkiss initiated a composting experiment with Hackney-based Xenia as a way to engage directly with biodegradable plastic and foreground the importance of lived experience, knowledge sharing and care – of people, objects (including compost) and community. Carne’s resulting book, A bitter orange tree and an orange tree: practices of care, encapsulates this approach. The book is a multi-textured publication, rich with writing across a myriad of modes: workshop notes, email exchanges, chat messages, personal recollections and conversations – some in translation, some about translation. The book’s title stems from a misunderstanding. As Carne reveals in the introduction, one of the participants, Fatima, spoke of having a bitter orange tree and an orange tree in her garden in Damascus. Carne admits that this sounded “odd” in translation and that her instinct was to edit the resulting text to remove what she had perceived to be an error. But it was explained that these are in fact two different types of tree. “My assumption,” admits Carne, “was wrong”.

Participation

Within each Trellis project are numerous, complex relationships structured in part by differentials of power, precarity and personal experience. An ethos shared across several projects has been “not about…, but with”: not about deaf people but with deaf people; not about autistic people but with autistic people. Sometimes this came from the researchers; sometimes from the artists. Any collaboration involves trust but for those Trellis projects working with marginalised and oppressed communities this was especially fundamental. “Trust to an autistic person is very important,” says artist Jon Adams. “We are so often on the receiving end of what everybody else wants for us,” he tells me, citing widespread media misrepresentation and mistreatment by charities and scientific researchers more interested in discovering biomarkers for autism than in addressing the questions that autistic people actually need answers to, especially around sleep, mental health and the alarmingly high suicide rate. “Society thinks we are a disease that needs to be cured, but we’re just a natural part of human evolution,” he says. “We’re not broken; we’re broken by society.”

As an artist with autism, Adams’ involvement in Flow Unlocked was also a sign that the project could be trusted by other autistic people. As one participant, Benny Wheeler, subsequently said:

It wasn’t like the kinds of research/focus groups I’d been used to; the ones that are more like data collection, where you answer the questions and go on your way never to be contacted again. We were kept involved and consulted on everything, and had a lot of input into how we wanted to be represented and what ideas we liked and didn’t like. Everyone was equally as important; our opinions were all valued.

This approach is vital for art but also for academic research. As Woll puts it: “working with the deaf community doesn’t just mean sharing research with people but listening to them. It means working with a community to find research questions that are important for the community.”

Power and payment

When it comes to engagements with academia, artists – usually operating as individuals – can find themselves subordinated to the needs of the institution. In participatory art, however, the artist often has power over the participants. Several Trellis artists sought to counter such hierarchies through a number of strategies including, quite simply, paying all participants. This is not always common practice in participatory art. Edwin Mingard, whose work has often involved co-production and establishing DIY and grass-roots initiatives, identified the dangers of a possible power imbalance between the artist and other collaborators. “If everybody is paid,” says Mingard, “everybody can mark out that time. It’s important for this project that lived experience is valued equally to artistic experience and is paid accordingly. And that is quite powerful, especially for somebody that has had difficult experiences. On this critical issue of how much we’re each paid, and therefore how much our experience is valued, we are level from the off.”

Mingard and Weitzberg’s project involved collaborating with people in east London who had first-hand experiences of oppression by the UK Home Office whose hostile environment policy, creeping surveillance and militarisation of data across many aspects of life can prevent access to healthcare or benefits even when people have every legal right to be here. Participants in the work include A, who fled civil war in Somalia and is a legitimate asylum seeker. Yet for over a decade, the Home Office has been attempting to deport him to Yemen, a war zone that A has never visited. These accounts are deeply shocking, says Mingard, and they are stories that people should know about.”

But Mingard’s approach goes beyond raising awareness. “It’s not just telling stories,” he says, “but exploring cultural traditions”, and doing so together. Mingard honed this way of working while making An Intermission (2020), a film made in collaboration with a network of young people experiencing homelessness in Stoke-On-Trent. For Trellis, he adopted a similar approach, involving participants at every stage of the process – from idea conception to filming and editing. One participant is a formerly undocumented Chinese artist, who wanted to perform a type of peasant opera from Fujian Province partly as a way to teach his son about his cultural heritage. He collaborated with Edwin and video artist Wei Zhou to create a section of the film, discussing ideas and rehearsing the performance together. This is a living cultural tradition that he had not performed publicly in 20 years.

Mingard’s collaborator on Trellis, UCL researcher Keren Weitzberg is an expert in the socio-political implications of digital technologies, especially biometrics in east Africa. She has argued that biometrics “opens a gulf between streamlined bureaucracies and people’s messy lives”. Perhaps Mingard and Weitzberg’s project might be seen as a kind of choreographic embrace of the messiness.

Both Mingard and Briony Campbell made clear to me that it is not only the ethics of collaboration that matter but also the quality of the artistic outcome. Campbell’s work as a photographer and film-maker has focused on relationships in a wide variety of contexts: from a collaboration between London rappers and musicians in Mali (Routes to Roots) to the artist’s own relationship with her dying father (The Dad Project). “Relationships are how I understand the world,” says Campbell, an approach she shares with Pavlopoulou, who has been working with autistic people and their families for nearly two decades. As Pavlopoulou puts it: “I have a passion working with multidisciplinary teams, experts by experience and scholar activists in community-based mental health research.”

A result of these shared approaches, Flow Unlocked focuses on the importance of intimate relationships for autistic people. The project saw Jon Adams return to drawing after a fifteen-year hiatus in which he focused mainly on sound and installation. Over the past year he has produced an array of incredibly detailed Biro drawings, entitled Covid Corvids, in response to conversations among the participants. Some of these are like formal portraits; some are full of the freedom of flight; others are articulations of trauma. One striking work shows an individual holding up a mammal skull in its dinosaur-like forearms before a group of four fellow corvids. Each grins to reveal rows of teeth – a nod to their dinosaur ancestors and to Adams’ past as a palaeontologist.

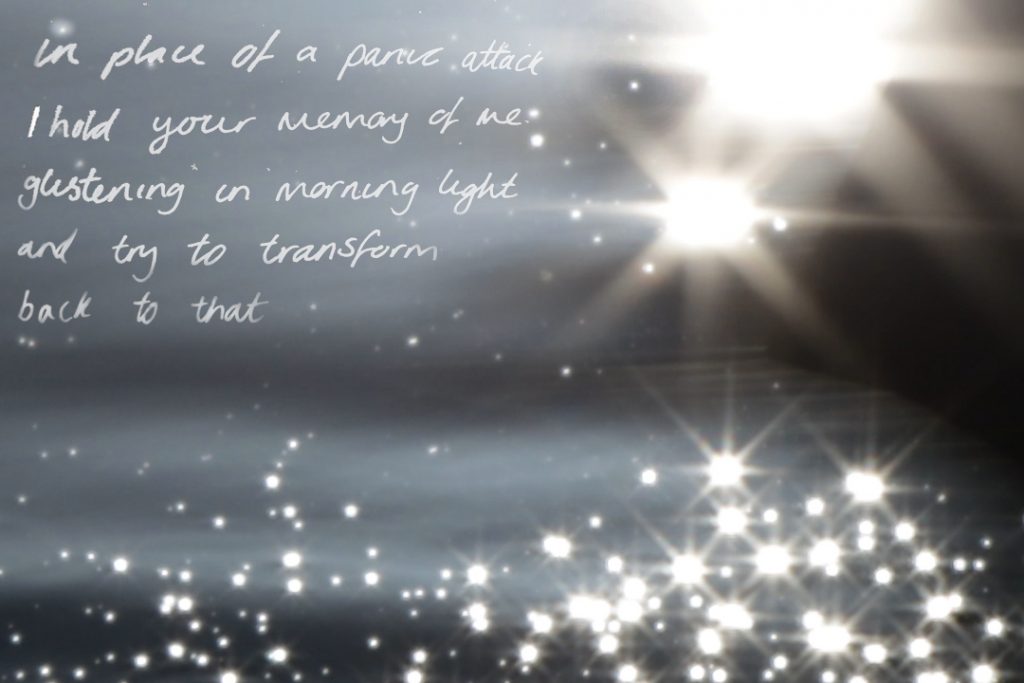

Campbell’s approach to making work is considered and time-consuming: for Trellis, she tried out multiple possibilities, making photographs and moving image works in response both to Adams’ drawings and to the poetry produced by autistic participants (including Adams) in the group workshops, and then adjusting the works and developing new ideas in response to further feedback from those involved. One iteratively produced work is a film of Adams reading a poem that he wrote in response to one of Campbell’s videos. To me, while Campbell’s work feels quiet and reparative, some of Adams’ drawings are strikingly tense. It might be a result of the medium (the uncompromising lines of Biro ink) or the way that Adams has characterised the subjects. You can trace the lines of attention from one individual to another, but the layers of emotion or intent remain powerfully open to interpretation.

Campbell speaks of a sense of responsibility to do justice to the contributions of others: “more than any project I’ve ever done, this has involved a weighing up of relationships and expectations,” Campbell says, with participants at once co-producers of the work and its most important audience. As she explains: “firstly, I am representing autistic people whose lived experience of autism I don’t share, and secondly the dual role of artist and facilitator creates multiple priorities that do not always easily align”.

At the same time, Campbell has shared with me an online sketchpad containing dozens of images: a moth held in a human hand; an orange bag floating in a canal; the blurred wings of a pigeon in flight. Each is like a multi-layered collage of ideas and emotions, text and image, but there is more: “how the images sit together is sometimes as important as the individual image,” says Campbell. This online format enables users to re-arrange the images as they wish, thereby offering the possibility of an open-ended composite artwork that questions a clear distinction between process and outcome, and allows the collaboration not only to remain ongoing but to grow.

The trellis effect

To me the open-ended interactive possibilities of Campbell’s work feel like a crystallisation of many of the questions being explored across the Trellis programme. If there is one thing that all five projects have in common, it is perhaps their engagement with the trellis itself. Not only has each project been shaped by the overarching structure of Trellis but each project has also created its own internal trellis-like structure. The result is almost fractal-like: trellises within trellises. This is true of the complex, sensitively thought-through processes that every project has entailed. But it also to varying extents, true of the finished works themselves (as if, having spent time with works such as Campbell’s, one could ever again draw such a clear line between process and outcome).

Carne’s A bitter orange tree and an orange tree, is one example of this trellis effect, with the material form and organisational structure of the book a way of gathering together an extraordinary array of contributions, each with its own voice and grammar. Mingard and Weitzberg’s film functions similarly, with each participant an artist in their own right, creating work that is collaborative (with Mingard and Weitzberg) but also independent, only coming together as a whole (if indeed a whole is what is formed) in the completed work itself. Mingard himself speaks of the work’s “modular structure”. Campbell creates an open-ended framework for a multiplicity of possible encounters while Heywood and Watt suggest that perhaps a place is like a trellis – a framework of connections between histories and traditions, memories and relationships – and they do so through a project that itself exists in many parts. Meanwhile, Aurangzeb-Tariq’s film offers her own time-lapse drawing as a kind of punctuation that structures the signed contributions from participants. Or perhaps it’s the other way round, with the signing like punctuation between the continually evolving sentences of Aurangzeb-Tariq’s endlessly beguiling time-lapse drawing.

The limits and beyond

Just as the university has long been modelled as an ideal community, so it can be tempting to see within collaborative art utopian possibilities for wider social change. Claire Bishop, a well-known critic of participatory art, has argued that the field demonstrates “a lack of faith in the intrinsic value of art and lack of faith in democratic political processes”. Bishop’s thesis has been challenged on several grounds but it remains important to acknowledge the limits of participatory art. There is a vast difference, as Black feminist author Brittney Cooper has argued, between having power and feeling empowered. In her memoir Eloquent Rage, Cooper writes that “power is conferred by social systems” while “empowerment is a feeling that individuals learn to cultivate when their power is compromised-to-nonexistent”.

Participatory art may be empowering, but what kind of power can it truly confer? Several Trellis projects are engaging with societal issues of vital importance: the misrepresentation of autistic people in the media, the silencing of their voices by those who claim to speak for them; the marginalisation of deaf people and culture, including the active suppression of Sign Language; the relentless persecution of vulnerable people by an increasingly oppressive state…

At their best, projects such as Trellis can offer both critique of today’s failing power systems and momentary utopian glimpses of something better. Some will hopefully have legacies beyond the duration of the collaborative process. But when the art stops, other, more powerful and better-funded institutions need to be willing to continue the work. The question now is: how will they? Words Tom Jeffries

Trellis Festival – 18th April Find out more HERE

There’s also a live site-specific moving image installation of ‘Mulberry Tree of Plenty’ in Bow from 15-18 April, 12-10pm daily at: Create Place, St Margaret’s House 26 Old Ford Road Bethnal Green London E2 9PL

The festival is part of the wider vision for UCL Public Art and Community Engagement to create opportunities for collaboration between artists, researchers and communities based around the future UCL East campus.