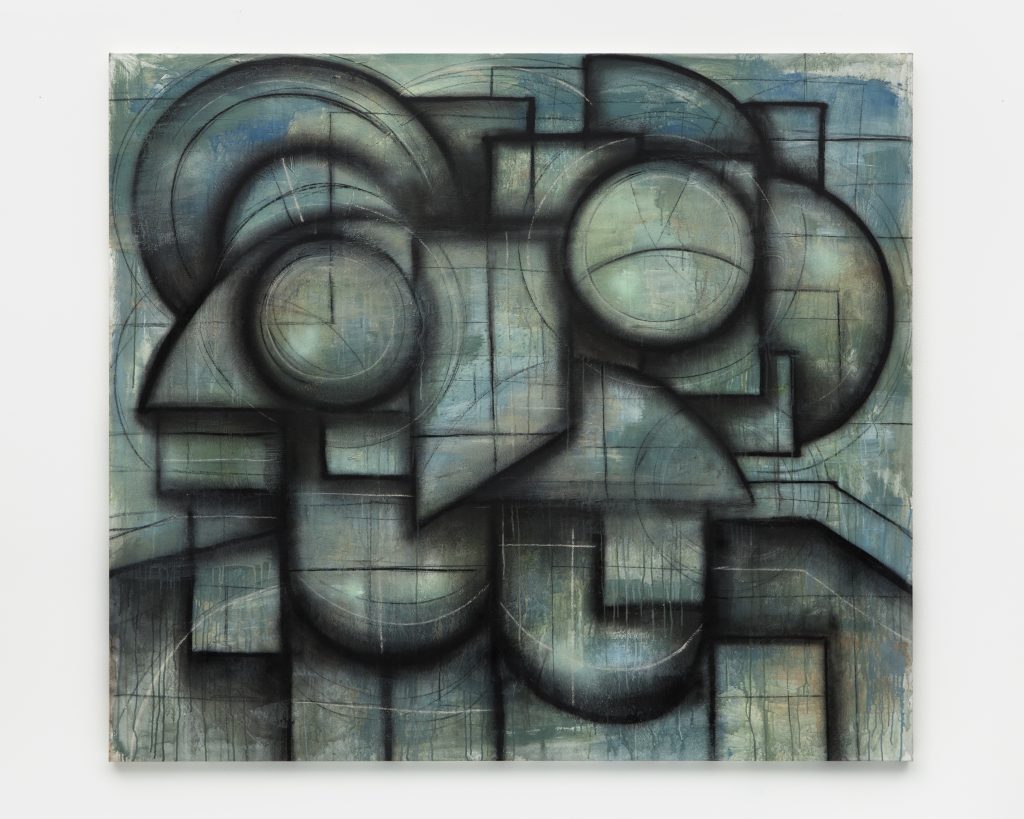

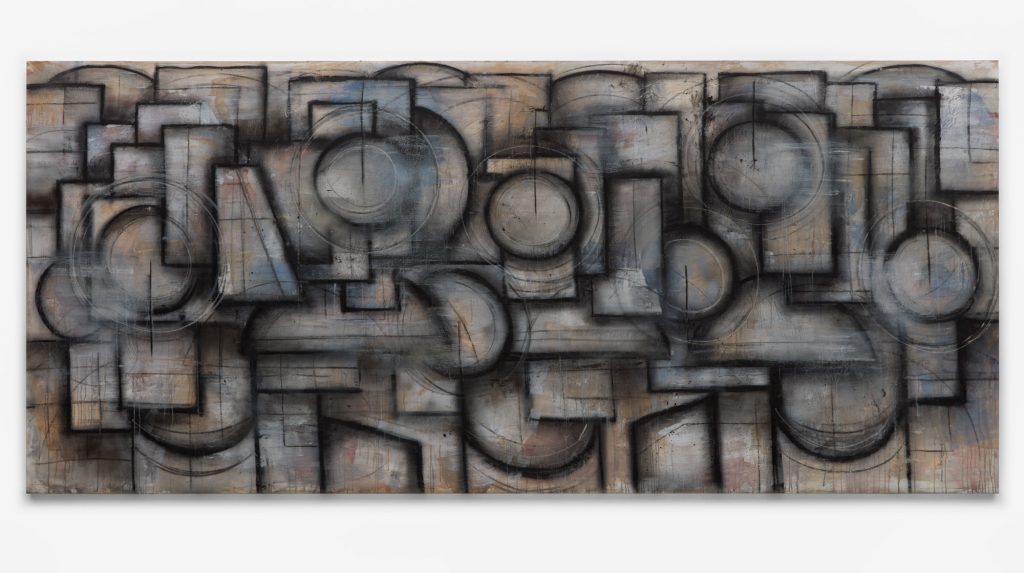

Lee Sharrock connected with self-taught Los-Angeles-based artist Devon DeJardin in advance of his upcoming solo show with DENK Gallery in LA, which features 20 new abstract canvas-based, paper and sculptural works created during the stormy lockdown era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Born in California in 1993, DeJardin found success with ‘Guardians’, his first solo exhibition at Coates and Scarry which sold out in 2018. His influences range from the intensely religious iconography of 15th Century early Netherlandish painter Dieric Bouts, via the cubist period of Picasso, to the Abstract Expressionism of Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, the figurative existential angst of Francis Bacon, all the way up to the present day with the large scale abstractions of artist Mark Bradford, who represented the USA at the Venice Biennale in 2016. DeJardin’s latest large-scale canvases could be described as a kind of abstracted Neo-Cubism.

Titled ‘Umgestalter’ – German for ‘Shifter of Shapes’, DeJardin’s exhibition references a line in “The Man Watching”, a poem written by Rainer Maria Rilke as an allegory to the biblical story of Jacob wrestling with the Angel. The poem examines the struggle of humanity against greater and more powerful forces, which could be seen as a prophetic message that we can apply to the present day struggle of humanity against Covid-19 and also climate change:

The storm, the shifter of shapes, drives on

across the woods and across time,

and the world looks as if it had no age:

the landscape, like a line in the psalm book,

is seriousness and weight and eternity.

What we choose to fight is so tiny!

What fights us is so great!

If only we would let ourselves be dominated

as things do by some immense storm,

we would become strong too, and not need names.

Lee Sharrock: Tell me a bit about yourself and how you became interested in art/ what age you were.

Devon DeJardin: There are two accounts that I specifically remember at an early age that initially led me down the rabbit hole of art. My earliest source of creative inspiration at age 8 came from my grandmother, who was a watercolour painter based in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Looking back, I think she was a pivotal figure who taught me about art and encouraged me to create, led by her own artistic passion. Born in England, she migrated to the United States, and took to painting historical buildings and running art workshops, developing a practice that resonated with the local community.

I used to visit my grandmother during the summer holidays , on one occasion, I stumbled into her basement-studio. She caught me ruffling through her materials but instead of getting angry and frustrated, she decided to teach me about painting. From then on, we would go to the beach to collect sea glass and make cement plates and collage style paintings. This was when I first began experimenting with non-traditional materials – sea glass, sand, ripped-up t-shirts, cloth – blending raw materials, to create art, which ultimately helped lead me to the place I am today.

The second account was seeing the painting “The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus” by Dieric Bouts at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston. This was the first painting I had ever seen that made me feel something deep. I felt a sense of horror, a sense of fear, a sense of intensity. I had never felt something like this outside of film. The painting itself had Hippolytus body spread, tortured and stretched across three panels. The painting itself just did not seem to stop. Everywhere I looked I felt that I was discovering a new sense of horror or pain. Although gruesome, I felt that this painting showed me the power of being able to communicate emotion through paint, texture and movement. It showed me that through imagery a viewer can connect deeply to something they may not ever be able to physically see in person.

Where do you live and work now, and what’s your usual medium, materials, method and starting point?

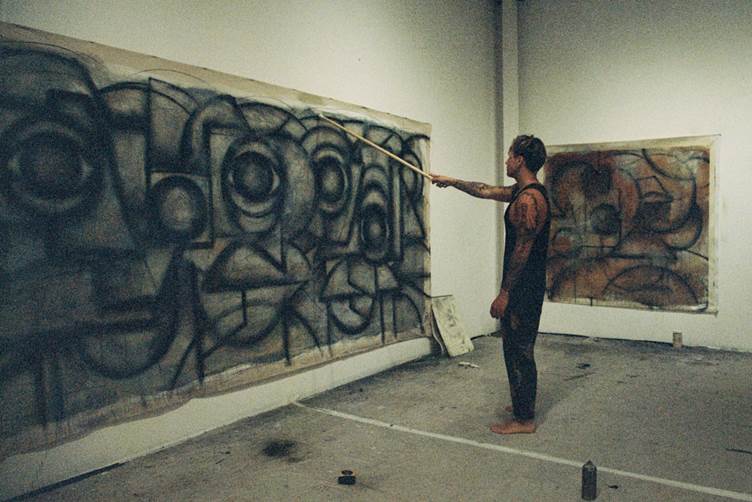

Originally from Portland, Oregon, I moved to Los Angeles at age 20. I am currently working out of my studio located in the arts district downtown. I find myself enjoying a disciplined schedule in my work approach and stick to a somewhat rigorous schedule. I typically am in the studio working Monday to Saturday from 9 am to 6 pm every day without fail. I have no shame in saying my mind is somewhat sporadic, hectic and disordered, so having this set schedule becomes almost a meditative approach to me. My materials used for creating works are all over the place. I don’t like to limit myself to one specific medium but find immense pleasure in a trial and error type of process. Charcoal, oil, acrylic, spray, pastel, seem to be my go to “tool bag”, but often I find that watering down paintings with mops and mixed acrylic water-sprays adds interesting elements. In a majority of my newer works I’ve introduced cement and in-house developed moulding pastes to deepen the surface levels of the canvas.

You quote a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke in the press release for your upcoming exhibition. It’s eerily prophetic and very apt for the Covid times we are living through, with lines like: I can tell by the way the trees beat, after so many dull days, on my worried windowpanes that a storm is coming.” How did you come across the poem and was this a starting point for your new exhibition?

Since the new year started, I have been having weekly discussions with Michael Brooks, a writer and adjunct professor of English at Hope College in Michigan. As I created my new body of work, Michael and I would discuss the narrative behind my work and the ways certain textures, colours, and movements could parallel with literature. I expressed to Michael that many of the works in the upcoming exhibition centred around battles with forces larger than us and around the idea of Man wrestling with God. A lot of visual artists have depicted the Genesis story of Jacob wrestling with the angel—which some people see as a metaphor for wrestling with God. Rembrandt depicted the scene, and so did Gustave Doré and Eugene Delacroix. Modernists too like Gauguin and Chagall painted it.

Michael saw a similar narrative between the lines of my work and wondered if any poets had explored the subject. Before long, we stumbled on Rilke’s “The Man Watching.” Right away, we saw how “eerily prophetic” the poem was for the current state of the world and how much of the poem seemed to align with the themes I explore in my new exhibition. Rilke talked about angels in different poems, and he seemed to explore them in the same ways I’ve explored my Guardians series and these new works. The connections kept deepening. We learned that Rilke had been the secretary for the sculptor Auguste Rodin and seemed pretty influenced by visual artists like Cézanne and El Greco. But more than Rilke’s life, we were struck by the words of “The Man Watching.” Rilke is talking about wrestling with angels, with God, with storms, and with forces way bigger than us. It was a perfect fit for my own explorations in this series and for what we think society is going through right now. We pulled the title of this exhibition – “Umgestalter,” which means shifter of shapes – from one line of the poem, which Rilke wrote in German.

Your new Denk Gallery exhibition is titled ‘Umgestalter’, the German word for ‘shape-shifter’ or ‘Transformer’, which is mentioned in Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem. How was the work in this exhibition influenced by the experience of living through the Covid-19 pandemic, and did you produce all the work during lockdown?

The term “Umgestalter” holds a madrigal of meanings. It speaks to the way my past struggles and storms have shifted my shape, as well as how as an artist my work has become abstracted from its original early form. It speaks of the way the present pandemic has altered the shape of society. It implies through Rilke a spiritual grapple and acquiescence to the forces beyond us that strengthen us through struggle. Within the term is the root “Gestalt,” a branch of holistic psychology that argues our perception focuses on the whole of something instead of its parts. And paradoxically, viewers come to better understand the strength of my work as I attempt the reduction and abstraction of the once original form (my previous body of work – GUARDIANS). Living through the Covid-19 pandemic has created a common understanding that all of us have been shifted and that regardless of our societal standings, we are all impacted by something outside our control. All of the work for this exhibition was created during the pandemic.

You have studied world religions at college and your first exhibition – in 2018 at Coates and Scary – was titled Guardians, while your new exhibition is influenced by the biblical story of Jacob grappling with the Angel. Would you say that you are religious or channelling your interest in spirituality and other worldliness into your artistic practice?

Is it religious to try and tell the story of humanity? My focus in painting is to start discussion. To allow a place where people feel that there is something greater speaking through the canvas. My time studying world religions showed me that there are forces working for, and against us. With Umgestalter, the creation of the work was focused on suppressing conscious control over the making process, allowing the unconscious mind to have great influence on the way paintings were formed. Phillip Guston talked about this idea of “Studio Ghosts”. “Studio Ghosts: When you’re in the studio painting, there are a lot of people in there with you – your teachers, friends, painters from history, critics… and one by one if you’re really painting, they walk out. And if you’re really painting YOU walk out.” I think that’s it… when you really are painting it is coming from something greater. You are absent. The hand, the arm, the brush are simply tools being used by a greater force at hand.

You’ve cited “The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus” by Dieric Bouts – a 15th Century early Netherlandish painter – as an early influence, a painting that you saw at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston. Yet your style is very abstract and your technique of applying paint to the canvas could be described as being influenced by the abstract expressionists. Who would you say are your biggest artistic influences – are they a mixture of old masters and more modern abstract painters?

Whenever people ask me where I find my inspiration/influences, I always ask them: do you mean in the individual of the artist or their artwork? Many artists inspire me both in their work as well as their character. I enjoy studying the biographies of artists. For example, I believe Francis Bacon is one of the few artists who was able to channel his authentic soul and spirit into his paintings successfully as well as being unapologetically himself. Another such figure is Picasso, the father of the Cubism movement and perhaps of modern art altogether. I am as profoundly inspired by his use of colour and geometric forms as by his personality and playfulness.

DD: I grew up immersed in traditional religious iconography. As such, I didn’t dwell on Old Masters or religious paintings when I began to work as an artist. However, one Old Master whose works touches me profoundly is Peter Paul Rubens. Rubens manages to depict biblical scenes with such mastery that moments of pain and triumph resonate with the viewer deeply even today, outside of a Christian theological context. One of my favorite contemporary artists is Mark Bradford. I am fascinated by the sense of scale in his works, as well as the diverse range of raw materials he employs to such stunning effect. In short, there are so many great artists, old and new, that inspire little aspects of my work.

You didn’t take a traditional route to becoming an artist – starting off as a fashion designer. So without going to art school, how did you get discovered for your first gallery show in 2018 and manage to sell all the paintings?

This is a question I am still struggling to fully comprehend. In 2019 I was painting in a small 10x18ft studio on Hollywood Blvd. I was isolated and remotely quiet from showing anyone my work. When I had a few paintings finished I would let friends come by and hang out in the studio. Slowly through word of mouth I was getting emails from collectors I couldn’t even begin to fathom. I sold a few early works to specific collectors and the word of mouth began to trickle. I got connected to Richard Scarry and Chippy Coates from a friend of a friend. We discussed the idea of doing a show to see if the paintings could speak to people. The exhibition happened in November of 2019 in Los Angeles, California. It was one of my first moments when I realized that art really does speak to people if you create the platform for it to be heard and if you share a narrative that is true to yourself. I am deeply grateful for everyone that supported my very early career.

Do you think that social media and the internet has made it easier to get discovered as an artist, by putting your work out there on platforms like Instagram?

I do believe social media has made it much easier to be discovered. Instagram profiles for artists act as mini-galleries and portfolios. It allows viewers to enter into the artists’ curated world and their identity. It has been shocking looking back at the many important connections I made early through social media that have helped build my foundation.

You talk about your struggles with depression and anxiety as an adolescent. Did making art enable you to channel your anxiety into another vessel, and did the creation of your ‘Guardian’s paintings act as some sort of catharsis for your depression?

I have found much freedom from past trauma and my struggles with anxiety and depression through the creation of art. I created the Guardian series as a symbolic form of protection so that all the work that followed would be “guarded” by these forces. I plan to reveal my story and my interactions with the world around me as I continue to create… and much of that story deals with darkness and wrestling with pain. Having Guardians as my first series of work is to point to the fact that there is a light at the end of the tunnel…now it’s time to work backwards.

What do you think of the new craze for NFTs and the insane auction price of $69,346,250 fetched for Beeple’s digital opus ’Everydays: the first 5,000 days’ at the Christie’s auction recently?

All I can say is good for him! I haven’t spent much time diving into the NFT world, and have stayed focused on creating works in the physical space. I think the NFT market space is proving that there are many different approaches to creating art. I just hope that artists in the space create work with an understanding of historical dialogue, and create work that touches on past, present and future events. Narrative is important and art should never be made with the intention of making quick money.

Any tips for young people thinking of becoming an artist?

If I had one bit of advice for young people thinking of becoming an artist, it would be to dive deep into understanding who you are as an individual. Search from within. Find ways to share your human experience. Interact with art history and touch on subjects from the past and present. Make work that has meaning and of cultural significance.

To join the DENK Gallery opening night in LA virtually on April 22nd, sign up via Devon’s site: devondejardin.com