This week I interviewed the performance artist Romina De Novellis about her exhibition at Alberta Pane Gallery, Paris which closed on Saturday. With “Si tu m’aimes, protège-moi”, the artist analysed the patriarchal roots of myths and rituals in order to subvert them. Rituals, in fact, must not be romanticised, but, rather, questioned.

“Who wants to go back to picking apples from a tree everyday? That’s not the point, as women and nature were already subjugated to men’s will in ancient times. If we go back to rituals, it must be to change the systems of oppression that originated from them”

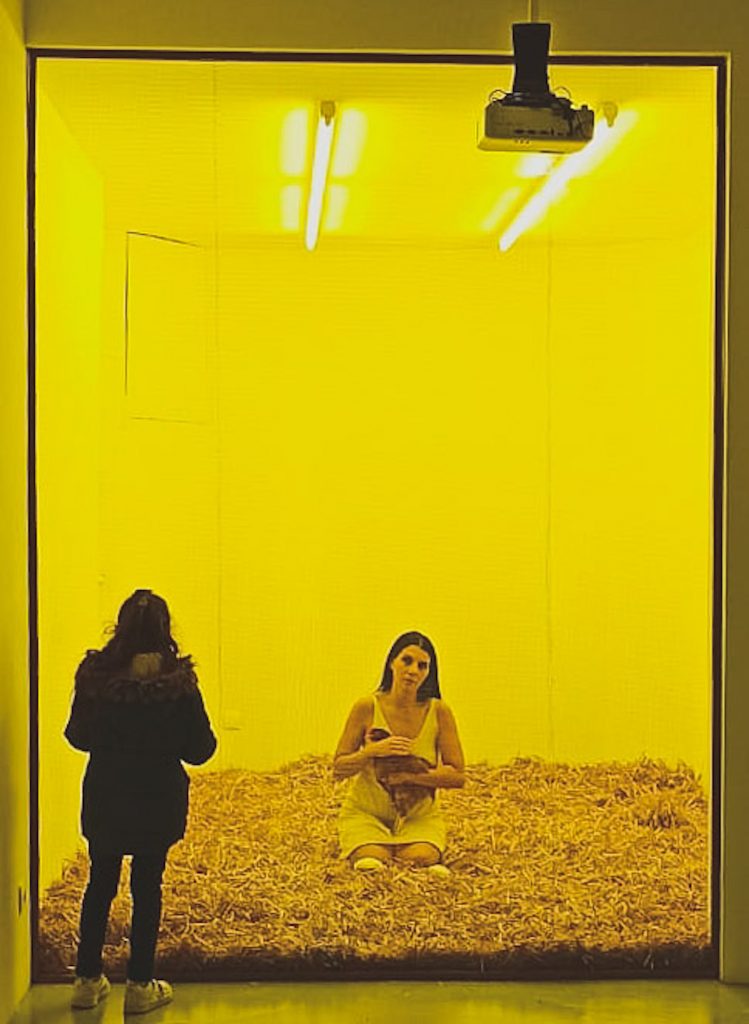

The performance ‘Si tu m’aimes, protégé-moi’ sees you enclosed into a cage; the public peeping into your space. You are caressing and shielding a hen, in an intimate and protective way. Does the visitor’s gaze feel like an intrusion into this intimate space? Is there a critique of this voyeurism?

I do not necessarily see it in terms of voyeurism, as this intrusion into my action is voluntary. It aims at starting a conversation. I reconnect to anthropologist Ernesto de Martino’s idea of “straniamento” (estrangement) – when something intimate has partaken in the public it causes a shock. This, in turn, creates an urgency to act. As my gestures become tragic, they assume a greater importance, as if they were a call to action. That’s why I never feel the viewer as something redundant, voyeuristic. I am asking the public to help me, to protect me, the same way I am caring for the chicken. The animal is just the medium.

At first, it seemed as if you were the one endangered from the visitors’ gaze, the ‘victim’ of this voyeurism. Talking to you now we gather you are actually placing the public in danger, shocking them, urging them to act.

My work focuses on presence, and my presence is very strong. There’s an energy that directly involves the spectators in my actions, creating an empathic relation whereby the public becomes part of my emotions and gestures. It’s a sensitive connection, there are no judgements or contrasts, only energy, feelings, connection.

I read your work is often informed by anthropology and eco-feminism. How do they influence your oeuvre?

As an artist from the South of Italy, I take with me a huge cultural background, my story, my life, my culture… As I employ my body and my story in my work I don’t perceive ecofeminism or anthropology influencing it, I just feel myself being a part of it. My body is already included in ecofeminism; my culture is already a component of anthropology. These theories only influence my theoretical work, not my gestures – they are already part of anthropology. I am a woman, my body is a female body so it already belongs to an ecofeminist story. I only represent a medium.

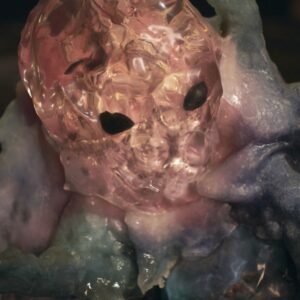

Romina De Novellis, 2021, Tentatives de résurection (2009), Polaroid, cement tile resin, wax, 20 x 20 cm, courtesy Galerie Alberta Pane

Food, animals, nature are recurring elements in your work. From an anthropological point of view, food is an incredibly strong signifier (I am thinking of Sidney Mintz or Carol J. Adams, for example). What kind of significance does it assume in your oeuvre?

I use food and animals to talk about rituals. People tend to have a very romanticised vision of our ancestral culture. Yet, it is exactly in ancient traditions that patriarchy and machismo first put down roots. Think only of dinner, lunch, eating ceremonies, pivotal rituals establishing the rules for becoming good women and men in society.

Before analysing the problem of food in society (like intensive farming, of which the chicken is a symbol), we must problematise rituals themselves, both inside the family and in society. It is in ancestral culture that the difference between women and men originated. Animals, too, live in a condition of subjugation, just like women, who will eventually cook the animal, as archaic rituals sanctioned.

The problem is not the role of animals in society, that’s just the final step of a culture that established very early in time that women had to be passive, objects, while animals were considered to be dirty, inferior, dispensable. Everything started from there, intensive farming is just the end of this process.

According to this vision ecofeminism must not be read as a nostalgia towards a pre-industrialised past. How do you interpret it?

Ecofeminist shouldn’t fool us into believing that archaic cultures were better. No! They were already trapped in a patriarchal ideology; their very inception was patriarchal. We need to go at the root of eco-feminism and find the causes that locked up both women and the environment in this condition of inferiority.

This is what ecofeminism is about: understanding that this nonsense of reducing women and nature to an overpowered role comes exactly from these phantasmal archaic cultures. So the one reason to bethink ancient times is to look out for what caused this oppression; to change the course of history, not to perpetuate it. Ecofeminism should’t be idealised as a throwback to planting trees or hoeing the ground. What would the point be? You won’t find female emancipation there, all the contrary. The more you travel back in time, the more you find women to be oppressed, burdened, violated.

“Si tu m’aimes, protege-moi” has a very ritualistic feeling – the folkloristic Italian song playing in the background, the disconcerting yellow light, the use of a hen, the mechanical gestures you repeat while gazing into space. What is the role of rituals in your works?

I am against rituals. I am against history. What I do in my work is an anti-ritual, an anti-history. I operate through a ritual to demystify it, to eradicate the romanticised narrative which built around it. I use popular symbols, typical of the Italian and Mediterranean culture so that anybody can identify with them and project onto them. At the same time, I create an uncanny effect, a straniemento. I like confusing the public, arousing an uncertainty as to whether I am performing a ritual, or criticising one.

By distancing the public from the ritual itself, making it uncanny, are you urging the public to act/reflect?

Yes. Onlookers feel part of the story, they recognise the cultural elements but, contemporarily, they feel estranged from it. Imagine a procession in the South of Italy – it’s a very peculiar moment, you don’t feel good as you walk through it. You perceive the tragedy, the suffering, without really understanding why. You become unsure: is it a tragedy what I am partaking in, or is it the representation of one? Are these performers crazy, or are they actors? It is within these blurred edges that I create my performances.

You tend to contrast the human body with the natural world, creating a sense of estrangement, which turns into dazzling horror when it comes to animals, bloody objects and iron cages. Have you ever thought about your works in terms of abjection (primal repression/disgust)?

It’s exactly that, the familiar becoming unfamiliar. And this all comes from my refusal of rituals. I use the ritual, but I reject it, making an anti-ritual. So mine is an abjection against society, against tradition. At the base, there’s a sort of rebellion on my side.

In the video, you hold onto a hen in a very protective way. You caress it and take it down from your lap gently; you shield its ear with a veil-gauze. Yet, usually, the action performed by women of covering the hen’s ears preluded to a violent gesture that could shock them, causing infertility. How is this tradition reinterpreted in your performance?

The fact that I bandage my head, alongside the hen’s one, actually satirises the impossibility to carry out such an operation on humans. Nobody would do that to people! The point isn’t reinterpreting a gesture from a ritual, but taking inspiration from an ancient ritual to denounce what society is not able to do with us.

During the performance, I completely idealise the animal. I am phobic of birds, but, as you said, I treat it as if it was my baby during the performance. I was able to find my dimension in this relationship, and this is what I choose to see in society. It’s difficult, but we can do it, all of us. The fact that I overcame my ornithophobia to create this symbiotic relationship proves it. If I can turn this fear into love then anybody can do it, society can do it.

Romina De Novellis, 2020, Si tu m’aimes, protège-moi, courtesy Galerie Alberta Pane, Copyright Mauro Bordin

In this gesture, we also perceive the brutality of an economy that demands animals to be constantly fertile as to keep producing goods to be commercialised. What kind of critique do you move here?

Taking care of animals and nature is fundamental; it becomes troubling as it transforms into brutal profiteering. The problem lays in exploitation, which determines an economy of death, careless dying, demographic depletion, desertification, mass migration. Exploitation speaks to the mass; any kind of relationship with the individual is lost. Vice versa, taking care of a hen is a unique, personal gesture. The only way to fight this economy of selling and exploiting is going back to these individual moments of authentic connection between an individual and animals, nature.

Just like the animal, the woman takes on a passive role, being just a pawn into a larger system – a ceremony, a ritual, or capitalism at large. Yet, here, you are the woman; it is your body to be at the centre of the performance. Did you approach performance as a sort of revenge of the female position?

Yes, even though I am not a fanatic of this women-only narrative and the re-centring of their role. Everyone needs to be at the centre. Of course, I am an activist, but I focus on rethinking all of the social rules, of which women’s role in society is just one of them. All canons need to change, feminism is no longer enough. We need queer, LGBTQ+, disability studies, we must rethink all bodies, overcoming this binary vision of women and men. What I advocate is a body-defence, a human defence, not merely a female-defence.

Why is feminism not enough anymore?

When the woman found a place in society, she almost forgot about people with disabilities, queers, mentally ill people. Feminism almost became like a competition, forgetting to involve all “categories” into its race. We must expand boundaries of what’s normal, what’s good, what’s beauty. It’s so anarchic to think that the world needs only feminists. Yes, I’m a feminist, but I am also more than that. Women are part of a larger system that needs to involve everybody. Only then will women find their place, and men discover the difficulties created by the involved.

Have you lived through a feminist prejudice?

I find obsolete the rhetoric of “women need power”. No! We need equality, not power. Feminism feels like a historical approach nowadays. Many people have come up to me saying I couldn’t be a feminist as I was beautiful. And this comes from a patriarchal approach, where the women become objectified if she’s beautiful. This embitters me! Beauty is a part of my body, it’s not a voluntary addition.

This takes me back to artist Hanna Wilke which still today receives negative critiques based on her beauty and therefore presumed impossible feminism.

To change a stereotype, you can’t impose another stereotype. You need to cancel the very idea of stereotype. You can’t contrast plastic surgery with extreme shabbiness; this was understandable in the ’70s, not now. I can be beautiful, have plastic surgery and still be a feminist. This aesthetic and appearances-based approach is tyranny. What matters should be the philosophy behind a work or a body, their meaning, not the face of the artist.

How should feminism evolve?

Feminism was born after frustration. It was complex before being a concept. We need to be reborn and restart in a new feminism that does not include frustration but focuses just on freedom. Feminism had to wage war, but during these endless fights, it also created clichés. I could understand it back then, where you had to fight against beauty cliches imposed by the patriarchy. What I cannot accept is seeing these stereotypes still being perpetuated now, in 2021. That’s why I say we need to evolve, to accept all bodies, to defeat all stereotypes and give freedom to everybody’s choices. That’s how you integrate human beings into the system. You can’t integrate it imposing another model to follow.

I am not criticising historical feminism, that was fundamental to get where we are, but we do need to evolve. Beauty itself is not objectifying, it is the gaze of the onlooker that objectifies it.

Galerie Alberta Pane: Romina De Novellis, SI TU M’AIMES, PROTÈGE-MOI.