It’s been a while, but the column about the value of art is back. I wrote the first 100 instalments over a period of two years when the commercial artworld was awash with money and that seemed to be the only important thing. Maybe nothing has changed there. After all, people still buy and sell art. But, in another sense, everything has changed in ways that nobody could have predicted and that has radically shifted the way we live and the way we interact with each other and with art. Anyway, after five years I’m back to thinking about the values art has aside from money – namely, in making our lives better, especially when everything is pretty grim. I’ll start with a lengthy review of Damien Hirst’s ‘End of a Century’ which may or may not open again at Newport Street Gallery, because, just in case you don’t get to see it you need to know why Damien Hirst is so, so good. I would say that, of course, but still…

Value and Ideas #101

Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night

The problem with death, as Samuel Beckett said, is that it does not require you to set aside a date in your diary. It just creeps up on you. Unless that is, you are in the middle of a Damien Hirst exhibition, where death is all around and where it is shrouded in the irresistible trappings of conceptual art. Hirst, you may recall, is a master of shock and awe, but his early work is much more shocking and much more beguiling than you probably remember, as ‘End of a Century’, at his Newport Street Gallery, robustly demonstrates.

The first striking thing about this show is its sobriety: the pallet is demure, there is a lot of wood and glass but not much bling, things are handmade, sometimes imperfectly, and the mood is unusually sombre, everything feels weighty, serious, robust. The show is a survey of sorts, drawn from Hirst’s personal collection, of works he made in the late 1980s at Goldsmiths and through the heyday of the 90s. The characteristic glint in the eye of 21st Century Hirst, where death is encrusted in diamonds, cabinets are gold-plated, gemstones of all colours abound and everything shimmers with the gleam and sparkle of manufactured perfection are nowhere to be seen.

It puts recent art history in perspective by reminding us that while we think of the YBAs as purveyors of sharks and Nazis, they were earnest young people, making serious art that people took seriously. It is a reminder that the early Hirst was not yet rich enough to poke fun at the artworld’s obsession with money, nor was he in a position to use expensive materials, so the early works – even those that are clearly manufactured at some cost – have a simplicity about them. The cabinets are made of MDF and Formica rather than polished steel, the medicine packaging is tatty and mouldy, the spots are wonky and anaemic and butterflies sit within wrinkled, haphazardly applied gloss paint. Indeed, the most pristine, ageless works here are the Natural History works – animals in formaldehyde – because Hirst perfected the preservation process early on. Gold, diamonds and mass-production came later, but Hirst is at his best not when he is decorating death, but when he is presenting it in its stark reality with a whiff of minimalism and an existential, conceptual flourish.

And so everywhere you look there is death. In the reception area, a shark, Myth Explored, Explained, Exploded (1993), seemingly swimming towards you in its crystalline blue fluid, open-mouthed with piercing eyes. For a moment, you think the first brush with death is your own, at the mercy of this hungry shark, but then – phew! – you walk round to the side of this wanton predator to discover that not only is it a (comparatively) small shark – big enough to take a limb in passing, but too small to swallow you whole – but also it is butchered into three pieces, each suspended for all eternity in its own separate vitrine of sacred formaldehyde. Alright, you think, so the joke’s on that shark whose death, while certainly not in vain, is the first lesson in the awful, unforgiving contingency of all earthly things. The sight of it, depending on where you stand, as being both whole and divided at the same time, like Schrödinger’s shark, is curious and the closest thing you’re going to get to a laugh until the very end of the show.

And so it continues. In the first room, When Logics Die (1991), features a brutal image of suicide by shotgun to the chin accompanied by an eerily serene assortment of banal medical paraphernalia arranged on a table as if someone was just coming or going, but the damage is already done so one wonders how those surgical instruments could possibly help now. Large chest freezers with glass tops, like you find in supermarkets, The Conference (The Quality of Being in the Future) (1991), stand in the middle of the room, looking, from a distance, like a pair of meaningless white boxes. That in itself seems stark, but it turns to shock when you peer through the glass to see row upon row of cows’ heads, frosty, raw and wrapped in clear plastic like Laura Palmer. This is Hirst at his absolute best: delivering shock value by being disgusting and horrifying with impeccable artistry; in this respect, he is the David Cronenberg of visual art. We are so accustomed to Hirst shocking through spectacle, ostentation or downright silliness that we forget that in the beginning, as a young man, he had a solid grasp of horror.

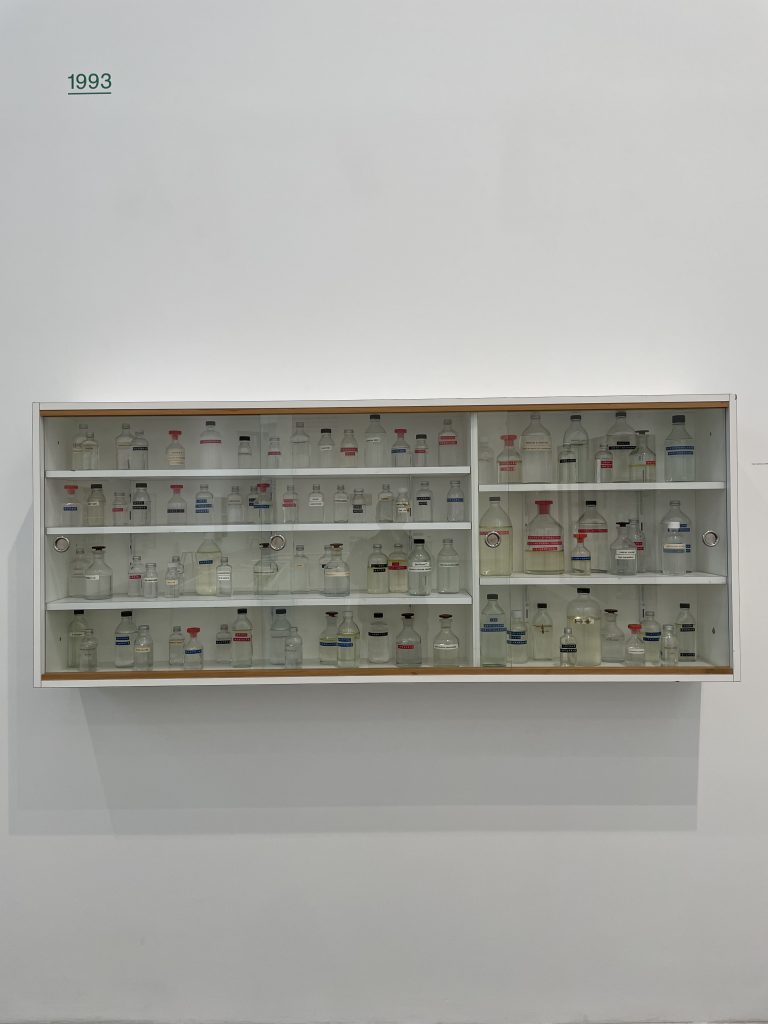

It continues in such a manner for a further four rooms, piling death upon death and horror upon horror. The earliest Medicine Cabinets, named after Sex Pistols and Clash songs, like Donald Judds but containing meticulously arranged pharmaceuticals, project spectral calm and promise salvation from death, but – like all such promises – they are ultimately empty because there is nothing within, just the packaging and therefore no tangible hope, as if the empty cardboard boxes are themselves just more tiny Judds pointlessly sitting within bigger Judds, eternally vacuous and ineffective. A butcher’s shop window containing pale meat, two more tiny sharks, a cabinet filled with delicately arranged cigarette butts – little pinpoints of death – a cabinet of preserved fish, an MDF prototype of the vast Pill Cabinets and more cows’ heads, more formaldehyde, some ducks and a scattering of spots and spins complete the picture. It’s relentless.

The most enchanting works in the show are the rarely seen and even more seldom talked about vitrine sculptures, which, as a matter of objective fact, are Hirst’s best works. Focus on Me My Pretty One, as I Focus on You (1997) is a cold, stark, white doctor’s office, pregnant with possibility but devoid of life, held in stasis; it has a tension, a sense of anticipation, at the same time as an emptiness, a threat, like the moment before bad news is delivered. Waster (1997) is a glass box packed tight with miscellaneous medical waste; all the resources and efforts used to sustain a life which was always going to end anyway. Another great glass box framed in solid hewn steel, completely empty, sturdy, brooding reminds us of Hirst’s minimal, conceptual beginnings. This empty vessel aches with intensity, which is not even very much alleviated by the spinning spin painting opposite. And then, in the sixth room, where the mood finally lightens with Hirst’s early forays into assemblage and those shiny pained pots, plates and boxes that prefigure the Spot Paintings, there is a vast vitrine called Art’s about Life, the Art World is about Money (1998). Inside, a puppet auctioneer sells a dodgy spot painting to a crowd of teddy bears who are surrounded by chocolate money. And that was a good decade before Hirst traded all his newest art for 111 million chocolate coins at Sotheby’s.

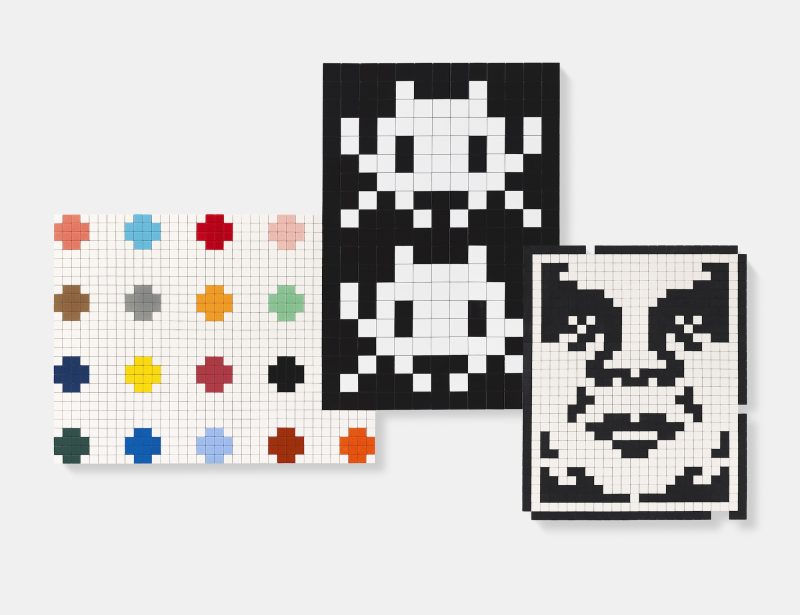

In fact, the themes of this show are so intense and so bleak that never before have you been so grateful for a Spot Painting. They pop up with the gusto of cheery old friends when you least expect it and most need it, such as opposite A Hundred Years (1991) and its massacre of flies, a forty-foot Spot Painting dampens the terror with seemingly endless technicolour. Here you see the evolution of the Spot Painting from its humble beginning as a mass of drippy spots in six colours (this very first Spot Painting (1986) just leans casually against the wall), through the initial efforts at painting within a pencil line and the phase where the hole of the compass remains visible and the pigment still feels slightly anaemic, right up to the sophisticated contemporary ones where the spots are so perfect and dense that they look like stickers.

And therein lies the core concept of ‘End of a Century’: the ostentation, spectacle and extravagance that we now associate with Hirst began with fairly basic ideas, humble materials and a whole lot of youthful earnestness, and then it evolved into something else with passing of time and spoils of wealth and fame. But what we see in this show is the bristling ambition of a young artist determined to put his stamp on art’s timeless themes of life and death. It reminds us that Hirst became famous for making arresting, aesthetically powerful and sometimes horrifying art that punches consciousness in the gut with its urgency and brilliance. The ideas may be old but what Hirst excels at is giving those ideas a contemporary, fresh form; he makes them look orderly, artistic and composed at the same time as capturing the nagging doubt, stultifying horror and dismal inevitability of death. And even though he makes art about death, he possesses, and always has, a profound love for the way things look, an urgency that ensures that, as Dylan Thomas said, we ‘rage, rage against the dying of the light’.